nullprogram.com/blog/2015/05/15/

This article has a followup.

Linux has an elegant and beautiful design when it comes to threads:

threads are nothing more than processes that share a virtual address

space and file descriptor table. Threads spawned by a process are

additional child processes of the main “thread’s” parent process.

They’re manipulated through the same process management system calls,

eliminating the need for a separate set of thread-related system

calls. It’s elegant in the same way file descriptors are elegant.

Normally on Unix-like systems, processes are created with fork(). The

new process gets its own address space and file descriptor table that

starts as a copy of the original. (Linux uses copy-on-write to do this

part efficiently.) However, this is too high level for creating

threads, so Linux has a separate clone() system call. It

works just like fork() except that it accepts a number of flags to

adjust its behavior, primarily to share parts of the parent’s

execution context with the child.

It’s so simple that it takes less than 15 instructions to spawn a

thread with its own stack, no libraries needed, and no need to call

Pthreads! In this article I’ll demonstrate how to do this on x86-64.

All of the code with be written in NASM syntax since, IMHO,

it’s by far the best (see: nasm-mode).

I’ve put the complete demo here if you want to see it all at once:

An x86-64 Primer

I want you to be able to follow along even if you aren’t familiar with

x86_64 assembly, so here’s a short primer of the relevant pieces. If

you already know x86-64 assembly, feel free to skip to the next

section.

x86-64 has 16 64-bit general purpose registers, primarily used to

manipulate integers, including memory addresses. There are many more

registers than this with more specific purposes, but we won’t need

them for threading.

rsp : stack pointerrbp : “base” pointer (still used in debugging and profiling)rax rbx rcx rdx : general purpose (notice: a, b, c, d)rdi rsi : “destination” and “source”, now meaningless namesr8 r9 r10 r11 r12 r13 r14 r15 : added for x86-64

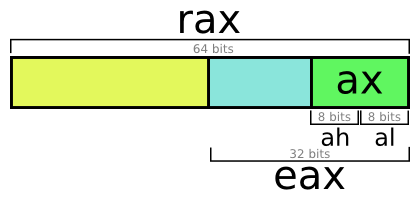

The “r” prefix indicates that they’re 64-bit registers. It won’t be

relevant in this article, but the same name prefixed with “e”

indicates the lower 32-bits of these same registers, and no prefix

indicates the lowest 16 bits. This is because x86 was originally a

16-bit architecture, extended to 32-bits, then to 64-bits.

Historically each of of these registers had a specific, unique

purpose, but on x86-64 they’re almost completely interchangeable.

There’s also a “rip” instruction pointer register that conceptually

walks along the machine instructions as they’re being executed, but,

unlike the other registers, it can only be manipulated indirectly.

Remember that data and code live in the same address space, so

rip is not much different than any other data pointer.

The Stack

The rsp register points to the “top” of the call stack. The stack

keeps track of who called the current function, in addition to local

variables and other function state (a stack frame). I put “top” in

quotes because the stack actually grows downward on x86 towards

lower addresses, so the stack pointer points to the lowest address on

the stack. This piece of information is critical when talking about

threads, since we’ll be allocating our own stacks.

The stack is also sometimes used to pass arguments to another

function. This happens much less frequently on x86-64, especially with

the System V ABI used by Linux, where the first 6 arguments are

passed via registers. The return value is passed back via rax. When

calling another function function, integer/pointer arguments are

passed in these registers in this order:

- rdi, rsi, rdx, rcx, r8, r9

So, for example, to perform a function call like foo(1, 2, 3), store

1, 2 and 3 in rdi, rsi, and rdx, then call the function. The mov

instruction stores the source (second) operand in its destination

(first) operand. The call instruction pushes the current value of

rip onto the stack, then sets rip (jumps) to the address of the

target function. When the callee is ready to return, it uses the ret

instruction to pop the original rip value off the stack and back

into rip, returning control to the caller.

mov rdi, 1

mov rsi, 2

mov rdx, 3

call foo

Called functions must preserve the contents of these registers (the

same value must be stored when the function returns):

- rbx, rsp, rbp, r12, r13, r14, r15

System Calls

When making a system call, the argument registers are slightly

different. Notice rcx has been changed to r10.

- rdi, rsi, rdx, r10, r8, r9

Each system call has an integer identifying it. This number is

different on each platform, but, in Linux’s case, it will never

change. Instead of call, rax is set to the number of the

desired system call and the syscall instruction makes the request to

the OS kernel. Prior to x86-64, this was done with an old-fashioned

interrupt. Because interrupts are slow, a special,

statically-positioned “vsyscall” page (now deprecated as a security

hazard), later vDSO, is provided to allow certain system

calls to be made as function calls. We’ll only need the syscall

instruction in this article.

So, for example, the write() system call has this C prototype.

ssize_t write(int fd, const void *buf, size_t count);

On x86-64, the write() system call is at the top of the system call

table as call 1 (read() is 0). Standard output is file

descriptor 1 by default (standard input is 0). The following bit of

code will write 10 bytes of data from the memory address buffer (a

symbol defined elsewhere in the assembly program) to standard output.

The number of bytes written, or -1 for error, will be returned in rax.

mov rdi, 1 ; fd

mov rsi, buffer

mov rdx, 10 ; 10 bytes

mov rax, 1 ; SYS_write

syscall

Effective Addresses

There’s one last thing you need to know: registers often hold a memory

address (i.e. a pointer), and you need a way to read the data behind

that address. In NASM syntax, wrap the register in brackets (e.g.

[rax]), which, if you’re familiar with C, would be the same as

dereferencing the pointer.

These bracket expressions, called an effective address, may be

limited mathematical expressions to offset that base address

entirely within a single instruction. This expression can include

another register (index), a power-of-two scalar (bit shift), and

an immediate signed offset. For example, [rax + rdx*8 + 12]. If

rax is a pointer to a struct, and rdx is an array index to an element

in array on that struct, only a single instruction is needed to read

that element. NASM is smart enough to allow the assembly programmer to

break this mold a little bit with more complex expressions, so long as

it can reduce it to the [base + index*2^exp + offset] form.

The details of addressing aren’t important this for this article, so

don’t worry too much about it if that didn’t make sense.

Allocating a Stack

Threads share everything except for registers, a stack, and

thread-local storage (TLS). The OS and underlying hardware will

automatically ensure that registers are per-thread. Since it’s not

essential, I won’t cover thread-local storage in this article. In

practice, the stack is often used for thread-local data anyway. The

leaves the stack, and before we can span a new thread, we need to

allocate a stack, which is nothing more than a memory buffer.

The trivial way to do this would be to reserve some fixed .bss

(zero-initialized) storage for threads in the executable itself, but I

want to do it the Right Way and allocate the stack dynamically, just

as Pthreads, or any other threading library, would. Otherwise the

application would be limited to a compile-time fixed number of

threads.

You can’t just read from and write to arbitrary addresses in

virtual memory, you first have to ask the kernel to allocate

pages. There are two system calls this on Linux to do this:

-

brk(): Extends (or shrinks) the heap of a running process, typically

located somewhere shortly after the .bss segment. Many allocators

will do this for small or initial allocations. This is a less

optimal choice for thread stacks because the stacks will be very

near other important data, near other stacks, and lack a guard page

(by default). It would be somewhat easier for an attacker to exploit

a buffer overflow. A guard page is a locked-down page just past the

absolute end of the stack that will trigger a segmentation fault on

a stack overflow, rather than allow a stack overflow to trash other

memory undetected. A guard page could still be created manually with

mprotect(). Also, there’s also no room for these stacks to grow.

-

mmap(): Use an anonymous mapping to allocate a contiguous set of

pages at some randomized memory location. As we’ll see, you can even

tell the kernel specifically that you’re going to use this memory as

a stack. Also, this is simpler than using brk() anyway.

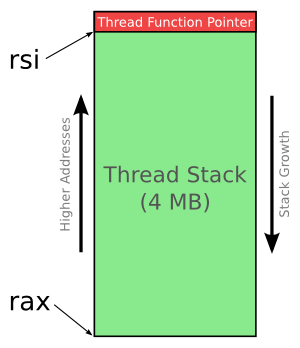

On x86-64, mmap() is system call 9. I’ll define a function to allocate

a stack with this C prototype.

void *stack_create(void);

The mmap() system call takes 6 arguments, but when creating an

anonymous memory map the last two arguments are ignored. For our

purposes, it looks like this C prototype.

void *mmap(void *addr, size_t length, int prot, int flags);

For flags, we’ll choose a private, anonymous mapping that, being a

stack, grows downward. Even with that last flag, the system call will

still return the bottom address of the mapping, which will be

important to remember later. It’s just a simple matter of setting the

arguments in the registers and making the system call.

%define SYS_mmap 9

%define STACK_SIZE (4096 * 1024) ; 4 MB

stack_create:

mov rdi, 0

mov rsi, STACK_SIZE

mov rdx, PROT_WRITE | PROT_READ

mov r10, MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_GROWSDOWN

mov rax, SYS_mmap

syscall

ret

Now we can allocate new stacks (or stack-sized buffers) as needed.

Spawning a Thread

Spawning a thread is so simple that it doesn’t even require a branch

instruction! It’s a call to clone() with two arguments: clone flags

and a pointer to the new thread’s stack. It’s important to note that,

as in many cases, the glibc wrapper function has the arguments in a

different order than the system call. With the set of flags we’re

using, it takes two arguments.

long sys_clone(unsigned long flags, void *child_stack);

Our thread spawning function will have this C prototype. It takes a

function as its argument and starts the thread running that function.

long thread_create(void (*)(void));

The function pointer argument is passed via rdi, per the ABI. Store

this for safekeeping on the stack (push) in preparation for calling

stack_create(). When it returns, the address of the low end of stack

will be in rax.

thread_create:

push rdi

call stack_create

lea rsi, [rax + STACK_SIZE - 8]

pop qword [rsi]

mov rdi, CLONE_VM | CLONE_FS | CLONE_FILES | CLONE_SIGHAND | \

CLONE_PARENT | CLONE_THREAD | CLONE_IO

mov rax, SYS_clone

syscall

ret

The second argument to clone() is a pointer to the high address of

the stack (specifically, just above the stack). So we need to add

STACK_SIZE to rax to get the high end. This is done with the lea

instruction: load effective address. Despite the brackets,

it doesn’t actually read memory at that address, but instead stores

the address in the destination register (rsi). I’ve moved it back by 8

bytes because I’m going to place the thread function pointer at the

“top” of the new stack in the next instruction. You’ll see why in a

moment.

Remember that the function pointer was pushed onto the stack for

safekeeping. This is popped off the current stack and written to that

reserved space on the new stack.

As you can see, it takes a lot of flags to create a thread with

clone(). Most things aren’t shared with the callee by default, so lots

of options need to be enabled. See the clone(2) man page for full

details on these flags.

CLONE_THREAD: Put the new process in the same thread group.CLONE_VM: Runs in the same virtual memory space.CLONE_PARENT: Share a parent with the callee.CLONE_SIGHAND: Share signal handlers.CLONE_FS, CLONE_FILES, CLONE_IO: Share filesystem information.

A new thread will be created and the syscall will return in each of

the two threads at the same instruction, exactly like fork(). All

registers will be identical between the threads, except for rax, which

will be 0 in the new thread, and rsp which has the same value as rsi

in the new thread (the pointer to the new stack).

Now here’s the really cool part, and the reason branching isn’t

needed. There’s no reason to check rax to determine if we are the

original thread (in which case we return to the caller) or if we’re

the new thread (in which case we jump to the thread function).

Remember how we seeded the new stack with the thread function? When

the new thread returns (ret), it will jump to the thread function

with a completely empty stack. The original thread, using the original

stack, will return to the caller.

The value returned by thread_create() is the process ID of the new

thread, which is essentially the thread object (e.g. Pthread’s

pthread_t).

Cleaning Up

The thread function has to be careful not to return (ret) since

there’s nowhere to return. It will fall off the stack and terminate

the program with a segmentation fault. Remember that threads are just

processes? It must use the exit() syscall to terminate. This won’t

terminate the other threads.

%define SYS_exit 60

exit:

mov rax, SYS_exit

syscall

Before exiting, it should free its stack with the munmap() system

call, so that no resources are leaked by the terminated thread. The

equivalent of pthread_join() by the main parent would be to use the

wait4() system call on the thread process.

More Exploration

If you found this interesting, be sure to check out the full demo link

at the top of this article. Now with the ability to spawn threads,

it’s a great opportunity to explore and experiment with x86’s

synchronization primitives, such as the lock instruction prefix,

xadd, and compare-and-exchange (cmpxchg). I’ll discuss

these in a future article.