nullprogram.com/blog/2016/03/31/

In this post I’m going to do a silly, but interesting, exercise that

should never be done in any program that actually matters. I’m going

write a program that changes one of its function definitions while

it’s actively running and using that function. Unlike last

time, this won’t involve shared libraries, but it will require

x86_64 and GCC. Most of the time it will work with Clang, too, but

it’s missing an important compiler option that makes it stable.

If you want to see it all up front, here’s the full source:

hotpatch.c

Here’s the function that I’m going to change:

void

hello(void)

{

puts("hello");

}

It’s dead simple, but that’s just for demonstration purposes. This

will work with any function of arbitrary complexity. The definition

will be changed to this:

void

hello(void)

{

static int x;

printf("goodbye %d\n", x++);

}

I was only going change the string, but I figured I should make it a

little more interesting.

Here’s how it’s going to work: I’m going to overwrite the beginning of

the function with an unconditional jump that immediately moves control

to the new definition of the function. It’s vital that the function

prototype does not change, since that would be a far more complex

problem.

But first there’s some preparation to be done. The target needs to

be augmented with some GCC function attributes to prepare it for its

redefinition. As is, there are three possible problems that need to be

dealt with:

- I want to hotpatch this function while it is being used by another

thread without any synchronization. It may even be executing the

function at the same time I clobber its first instructions with my

jump. If it’s in between these instructions, disaster will strike.

The solution is the ms_hook_prologue function attribute. This tells

GCC to put a hotpatch prologue on the function: a big, fat, 8-byte NOP

that I can safely clobber. This idea originated in Microsoft’s Win32

API, hence the “ms” in the name.

- The prologue NOP needs to be updated atomically. I can’t let the

other thread see a half-written instruction or, again, disaster. On

x86 this means I have an alignment requirement. Since I’m

overwriting an 8-byte instruction, I’m specifically going to need

8-byte alignment to get an atomic write.

The solution is the aligned function attribute, ensuring the

hotpatch prologue is properly aligned.

- The final problem is that there must be exactly one copy of this

function in the compiled program. It must never be inlined or

cloned, since these won’t be hotpatched.

As you might have guessed, this is primarily fixed with the noinline

function attribute. Since GCC may also clone the function and call

that instead, so it also needs the noclone attribute.

Even further, if GCC determines there are no side effects, it may

cache the return value and only ever call the function once. To

convince GCC that there’s a side effect, I added an empty inline

assembly string (__asm("")). Since puts() has a side effect

(output), this isn’t truly necessary for this particular example, but

I’m being thorough.

What does the function look like now?

__attribute__ ((ms_hook_prologue))

__attribute__ ((aligned(8)))

__attribute__ ((noinline))

__attribute__ ((noclone))

void

hello(void)

{

__asm("");

puts("hello");

}

And what does the assembly look like?

$ objdump -Mintel -d hotpatch

0000000000400848 <hello>:

400848: 48 8d a4 24 00 00 00 lea rsp,[rsp+0x0]

40084f: 00

400850: bf d4 09 40 00 mov edi,0x4009d4

400855: e9 06 fe ff ff jmp 400660 <puts@plt>

It’s 8-byte aligned and it has the 8-byte NOP: that lea instruction

does nothing. It copies rsp into itself and changes no flags. Why

not 8 1-byte NOPs? I need to replace exactly one instruction with

exactly one other instruction. I can’t have another thread in between

those NOPs.

Hotpatching

Next, let’s take a look at the function that will perform the

hotpatch. I’ve written a generic patching function for this purpose.

This part is entirely specific to x86.

void

hotpatch(void *target, void *replacement)

{

assert(((uintptr_t)target & 0x07) == 0); // 8-byte aligned?

void *page = (void *)((uintptr_t)target & ~0xfff);

mprotect(page, 4096, PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC);

uint32_t rel = (char *)replacement - (char *)target - 5;

union {

uint8_t bytes[8];

uint64_t value;

} instruction = { {0xe9, rel >> 0, rel >> 8, rel >> 16, rel >> 24} };

*(uint64_t *)target = instruction.value;

mprotect(page, 4096, PROT_EXEC);

}

It takes the address of the function to be patched and the address of

the function to replace it. As mentioned, the target must be 8-byte

aligned (enforced by the assert). It’s also important this function is

only called by one thread at a time, even on different targets. If

that was a concern, I’d wrap it in a mutex to create a critical

section.

There are a number of things going on here, so let’s go through them

one at a time:

Make the function writeable

The .text segment will not be writeable by default. This is for both

security and safety. Before I can hotpatch the function I need to make

the function writeable. To make the function writeable, I need to make

its page writable. To make its page writeable I need to call

mprotect(). If there was another thread monkeying with the page

attributes of this page at the same time (another thread calling

hotpatch()) I’d be in trouble.

It finds the page by rounding the target address down to the nearest

4096, the assumed page size (sorry hugepages). Warning: I’m being a

bad programmer and not checking the result of mprotect(). If it

fails, the program will crash and burn. It will always fail systems

with W^X enforcement, which will likely become the standard in the

future. Under W^X (“write XOR execute”), memory can either

be writeable or executable, but never both at the same time.

What if the function straddles pages? Well, I’m only patching the

first 8 bytes, which, thanks to alignment, will sit entirely inside

the page I just found. It’s not an issue.

At the end of the function, I mprotect() the page back to

non-writeable.

Create the instruction

I’m assuming the replacement function is within 2GB of the original in

virtual memory, so I’ll use a 32-bit relative jmp instruction. There’s

no 64-bit relative jump, and I only have 8 bytes to work within

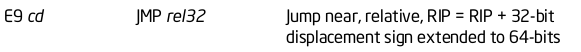

anyway. Looking that up in the Intel manual, I see this:

Fortunately it’s a really simple instruction. It’s opcode 0xE9 and

it’s followed immediately by the 32-bit displacement. The instruction

is 5 bytes wide.

To compute the relative jump, I take the difference between the

functions, minus 5. Why the 5? The jump address is computed from the

position after the jump instruction and, as I said, it’s 5 bytes

wide.

I put 0xE9 in a byte array, followed by the little endian

displacement. The astute may notice that the displacement is signed

(it can go “up” or “down”) and I used an unsigned integer. That’s

because it will overflow nicely to the right value and make those

shifts clean.

Finally, the instruction byte array I just computed is written over

the hotpatch NOP as a single, atomic, 64-bit store.

*(uint64_t *)target = instruction.value;

Other threads will see either the NOP or the jump, nothing in between.

There’s no synchronization, so other threads may continue to execute

the NOP for a brief moment even through I’ve clobbered it, but that’s

fine.

Trying it out

Here’s what my test program looks like:

void *

worker(void *arg)

{

(void)arg;

for (;;) {

hello();

usleep(100000);

}

return NULL;

}

int

main(void)

{

pthread_t thread;

pthread_create(&thread, NULL, worker, NULL);

getchar();

hotpatch(hello, new_hello);

pthread_join(thread, NULL);

return 0;

}

I fire off the other thread to keep it pinging at hello(). In the

main thread, it waits until I hit enter to give the program input,

after which it calls hotpatch() and changes the function called by

the “worker” thread. I’ve now changed the behavior of the worker

thread without its knowledge. In a more practical situation, this

could be used to update parts of a running program without restarting

or even synchronizing.

Further Reading

These related articles have been shared with me since publishing this

article: