nullprogram.com/blog/2019/01/25/

Follow-up: Tips for more effective fuzz testing with AFL++

This article was discussed on Hacker News and on reddit.

In 2007 I wrote a pair of modding tools, binitools, for a space

trading and combat simulation game named Freelancer. The game

stores its non-art assets in the format of “binary INI” files, or “BINI”

files. The motivation for the binary format over traditional INI files

was probably performance: it’s faster to load and read these files than

it is to parse arbitrary text in INI format.

Much of the in-game content can be changed simply by modifying these

files — changing time names, editing commodity prices, tweaking ship

statistics, or even adding new ships to the game. The binary nature

makes them unsuitable to in-place modification, so the natural approach

is to convert them to text INI files, make the desired modifications

using a text editor, then convert back to the BINI format and replace

the file in the game’s installation.

I didn’t reverse engineer the BINI format, nor was I the first person

the create tools to edit them. The existing tools weren’t to my tastes,

and I had my own vision for how they should work — an interface more

closely following the Unix tradition despite the target being a

Windows game.

When I got started, I had just learned how to use yacc (really

Bison) and lex (really flex), as well as

Autoconf, so I went all-in with these newly-discovered tools. It was

exciting to try them out in a real-world situation, though I slavishly

aped the practices of other open source projects without really

understanding why things were they way they were. Due to the use of

yacc/lex and the configure script build, compiling the project required

a full, Unix-like environment. This is all visible in the original

version of the source.

The project was moderately successful in two ways. First, I was able to

use the tools to modify the game. Second, other people were using the

tools, since the binaries I built show up in various collections of

Freelancer modding tools online.

The Rewrite

That’s the way things were until mid-2018 when I revisited the project.

Ever look at your own old code and wonder what they heck you were

thinking? My INI format was far more rigid and strict than necessary, I

was doing questionable things when writing out binary data, and the

build wasn’t even working correctly.

With an additional decade of experience under my belt, I knew I could do

way better if I were to rewrite these tools today. So, over the course

of a few days, I did, from scratch. That’s what’s visible in the master

branch today.

I like to keep things simple which meant no more Autoconf, and

instead a simple, portable Makefile. No more yacc or lex, and

instead a hand-coded parser. Using only conforming, portable C. The

result was so simple that I can build using Visual Studio in a

single, short command, so the Makefile isn’t all that necessary. With

one small tweak (replace stdint.h with a typedef), I can even build

and run binitools in DOS.

The new version is faster, leaner, cleaner, and simpler. It’s far more

flexible about its INI input, so its easier to use. But is it more

correct?

Fuzzing

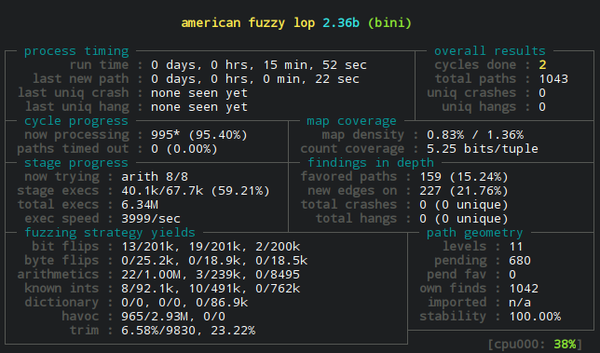

I’ve been interested in fuzzing for years, especially

american fuzzy lop, or afl. However, I wasn’t having success

with it. I’d fuzz some of the tools I use regularly, and it wouldn’t

find anything of note, at least not before I gave up. I fuzzed my

JSON library, and somehow it turned up nothing. Surely my

JSON parser couldn’t be that robust already, could it? Fuzzing just

wasn’t accomplishing anything for me. (As it turns out, my JSON

library is quite robust, thanks in large part to various

contributors!)

So I’ve got this relatively new INI parser, and while it can

successfully parse and correctly re-assemble the game’s original set of

BINI files, it hasn’t really been exercised that much. Surely there’s

something in here for a fuzzer to find. Plus I don’t even have to write

a line of code in order to run afl against it. The tools already read

from standard input by default, which is perfect.

Assuming you’ve got the necessary tools installed (make, gcc, afl),

here’s how easy it is to start fuzzing binitools:

$ make CC=afl-gcc

$ mkdir in out

$ echo '[x]' > in/empty

$ afl-fuzz -i in -o out -- ./bini

The bini utility takes INI as input and produces BINI as output, so

it’s far more interesting to fuzz than its inverse, unbini. Since

unbini parses relatively simple binary data, there are (probably) no

bugs for the fuzzer to find. I did try anyway just in case.

In my example above, I swapped out the default compiler for afl’s GCC

wrapper (CC=afl-gcc). It calls GCC in the background, but in doing so

adds its own instrumentation to the binary. When fuzzing, afl-fuzz

uses that instrumentation to monitor the program’s execution path. The

afl whitepaper explains the technical details.

I also created input and output directories, placing a minimal, working

example into the input directory, which gives afl a starting point. As

afl runs, it mutates a queue of inputs and observes the changes on the

program’s execution. The output directory contains the results and, more

importantly, a corpus of inputs that cause unique execution paths. In

other words, the fuzzer output will be lots of inputs that exercise many

different edge cases.

The most exciting and dreaded result is a crash. The first time I ran it

against binitools, bini had many such crashes. Within minutes, afl

was finding a number of subtle and interesting bugs in my program, which

was incredibly useful. It even discovered an unlikely stale pointer

bug by exercising different orderings for various memory

allocations. This particular bug was the turning point that made me

realize the value of fuzzing.

Not all the bugs it found led to crashes. I also combed through the

outputs to see what sorts of inputs were succeeding, what was failing,

and observe how my program handled various edge cases. It was rejecting

some inputs I thought should be valid, accepting some I thought should

be invalid, and interpreting some in ways I hadn’t intended. So even

after I fixed the crashing inputs, I still made tweaks to the parser to

fix each of these troublesome inputs.

Building a test suite

Once I combed out all the fuzzer-discovered bugs, and I agreed with the

parser on how all the various edge cases should be handled, I turned the

fuzzer’s corpus into a test suite — though not directly.

I had run the fuzzer in parallel — a process that is explained in the

afl documentation — so I had lots of redundant inputs. By redundant I

mean that the inputs are different but have the same execution path.

Fortunately afl has a tool to deal with this: afl-cmin, the corpus

minimization tool. It eliminates all the redundant inputs.

Second, many of these inputs were longer than necessary in order to

invoke their unique execution path. There’s afl-tmin, the test case

minimizer, which I used to further shrink my test corpus.

I sorted the valid from invalid inputs and checked them into the

repository. Have a look at all the wacky inputs invented by the

fuzzer starting from my single, minimal input:

This essentially locks down the parser, and the test suite ensures a

particular build behaves in a very specific way. This is most useful

for ensuring that builds on other platforms and by other compilers are

indeed behaving identically with respect to their outputs. My test suite

even revealed a bug in diet libc, as binitools doesn’t pass the tests

when linked against it. If I were to make non-trivial changes to the

parser, I’d essentially need to scrap the current test suite and start

over, having afl generate an entire new corpus for the new parser.

Fuzzing has certainly proven itself to be a powerful technique. It found

a number of bugs that I likely wouldn’t have otherwise discovered on my

own. I’ve since gotten more savvy on its use and have used it on other

software — not just software I’ve written myself — and discovered more

bugs. It’s got a permanent slot on my software developer toolbelt.