nullprogram.com/blog/2008/02/22/

I have gotten several e-mails lately about using GNU Octave. One

specifically was about blurring images in Octave. In response, I am

writing this in-depth post to cover spatial filters, and how to use

them in GNU Octave (a free implementation of the Matlab programming

language). This should be the sort of information you would find near

the beginning of an introductory digital image processing textbook,

but written out more simply. In the future, I will probably be writing

a post covering non-linear spatial and/or frequency domain filters in

Octave.

If you want to follow along in Octave, I strongly recommend that you

upgrade to the new Octave 3.0. It is considered stable, but differs

significantly from Octave 2.1, which many people may be used to. You

will also need to install

the image

processing package

from Octave-Forge. To get

help with any Octave function, just type help

<function>.

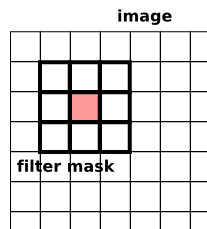

The most common linear spatial image filtering

involves

convolving a filter mask, sometimes called a convolution

kernel, over an image, which is a two-dimensional matrix. In the

case of an RGB color

image, the image is actually composed of three two-dimensional

grayscale images, each representing a single color, where each is

convolved with the filter mask separately.

Convolution is sliding a mask over an image. The new value at the

mask's position is the sum of the value of each element of the mask

multiplied by the value of the image at that position. For an example,

let's start with 1-dimensional convolution. Define a mask,

5 3 2 4 8

The 2 is the anchor for the mask. Define an image,

0 0 1 2 1 0 0

As we convolve, the mask will extend beyond the image at the

edges. One way to handle this is to pad the image with 0's. We start

by placing the mask at the left edge. (zero-padding is underlined)

Mask: 5 3 2 4 8

Image: 0 0 0 0 1 2 1 0 0

The first output value is 8, as every other element of the mask is

multiplied by zero.

Output: 8 x x x x x x

Now, slide the mask over by one position,

Mask: 5 3 2 4 8

Image: 0 0 0 1 2 1 0 0

The output here is 20, because 8*2 + 4*1 = 20;

Output: 8 20 x x x x x

If we continue sliding the mask along, the output becomes,

Output: 8 20 18 11 13 13 5

Here is the correlation done in Octave interactively,

(filter2() is the correlation function).

octave> filter2([5 3 2 4 8], [0 0 1 2 1 0 0])

ans =

8 20 18 11 13 13 5

The same thing happens in two-dimensional convolution, with the mask

moving in the vertical direction as well, so that each element in the

image is covered.

Sometimes you will hear this described as correlation

(Octave's filter2) or convolution

(Octave's conv2). The only difference between these

operations is that in convolution the filter masked is rotated 180

degrees. Whoop-dee-doo. Most of the time your filter is probably

symmetrical anyway. So, don't worry much about the difference between

these two. Especially in Octave, where rotating a matrix is easy

(see rot90()).

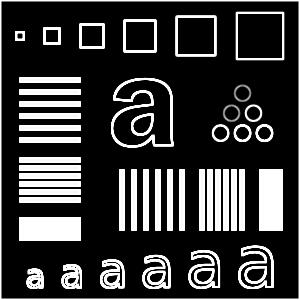

Now that we know convolution, let's introduce the sample image we will

be using. I carefully put this together

in Inkscape, which should give

us a nice scalable test image. When converting to a raster format,

there is a bit of unwanted anti-aliasing going on (couldn't find a way

to turn that off), but it is minimal.

Save that image (the PNG file, not the linked SVG file) where you can

get to it in Octave. Now, let's load the image into Octave

using imread().

m = imread("image-test.png");

The image is a grayscale image, so it has only one layer. The size

of m should be 300x300. You can check this like so (note

the lack of semicolon so we can see the output),

size(m)

You can view the image stored in m

with imshow. It doesn't care about the image dimensions

or size, so until you resize the plot window, it will probably be

stretched.

imshow(m);

Now, let's make an extremely simple 5x5 filter mask.

f = ones(5) * 1/25

Octave will show us what this matrix looks like.

f =

0.040000 0.040000 0.040000 0.040000 0.040000

0.040000 0.040000 0.040000 0.040000 0.040000

0.040000 0.040000 0.040000 0.040000 0.040000

0.040000 0.040000 0.040000 0.040000 0.040000

0.040000 0.040000 0.040000 0.040000 0.040000

This filter mask is called an averaging filter. It simply

averages all the pixels around the image (think about how this works

out in the convolution). The effect will be to blur the image. It is

important to note here that the sum of the elements is 1 (or 100% if

you are thinking of averages). You can check it like so,

sum(f(:))

Now, to convolve the image with the filter mask

using filter2().

ave_m = filter2(f, m);

You can view the filtered image again with imshow()

except that we need to first convert the image matrix to a matrix of

8-bit unsigned integers. It is kind of annoying that we need this, but

this is the way it is as of this writing.

ave_m = uint8(ave_m);

imshow(ave_m);

Or, we can save this image to a file

using imwrite(). Just like with imshow(),

you will first need to convert the image to uint8.

imwrite("averaged.png", ave_m);

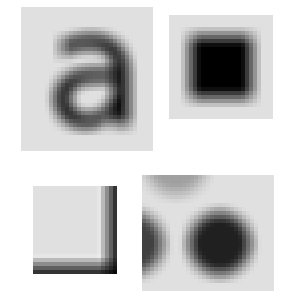

There are a few things to notice about this image. First there is a

black border around the outside of the filtered image. This is due to

the zero-padding (black border) done by filter2(). The

border of the image had 0's averaged into them. Second, some parts of

the blurred image are "noisy". Here are some selected parts at 4x zoom.

Notice how the circle, and the "a" seem a little bit boxy? This is due

to the shape of our filter. Also notice that the blurring isn't as

smooth as it could be. This is because the filter itself isn't very

smooth. We'll fix both these problems with a new filter later.

First, here is how we can fix the border problem: we pad the image

with itself. Octave provides us three easy ways to do this. The first

is replicate padding: the padding outside the image is the same as the

nearest border pixel in the image. Circular padding: the padding from

from the opposite side of the image, as if it was wrapped. This would

be a good choice for a periodic image. Last, and probably the most

useful is symmetric: the padding is a mirror reflection of the image

itself.

To apply symmetric padding, we use the padarray()

function. We only want to pad the image by the amount that the mask

will "hang off". Let's pad the original image for a 9x9 filter, which

will hang off by 4 pixels each way,

mpad = padarray(m, [4 4], "symmetric");

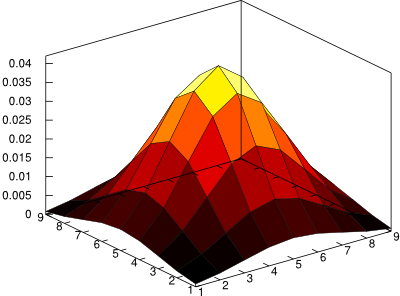

Next, we will replace the averaging filter with a 2D Gaussian

distribution. The Gaussian, or normal, distribution has many wonderful

and useful properties (as a statistics professor I had once said,

anyone who considers themselves to be educated should know about the

normal distribution). One property that makes it useful is that if we

integrate the Gaussian distribution from minus infinity to infinity,

the result is 1. The easiest way to get the curve without having to

type in the equation is using fspecial(): a special

function for creating image filters.

f_gauss = fspecial("gaussian", 9, 2);

This creates a 9x9 Gaussian filter with variance 2. The variance

controls the effective size of the filter. Increasing the size of the

filter from 9 to 99 will actually have virtually no impact on the

final result. It just needs to be large enough to cover the curve. Six

times the variance covers over 99% of the curve, so for a variance of

2, a filter of size 7x7 (always make your filters odd in size) is

plenty. A larger filter means a longer convolution time. Here is what

the 9x9 filter looks like,

And to filter with the Gaussian,

gauss_m = filter2(f_gauss, mpad, "valid";

gauss_m = uint8(guass_m);

Notice the extra argument "valid"? Since we padded the

image before filtering, we don't want this padding to be part of the

image result. filter2() normally returns an image of the

same size as the input image, but we only want the part that didn't

undergo (additional) zero-padding. The result is now the same size as

the original image, but without the messy border,

Also, compare the result to the average filter above. See how much

smoother this image is? If you are interested in blurring an image,

you will generally want to go with a Gaussian filter like this.

Now I will let you in on a little shortcut. In Matlab, there is a

function called imfilter which does the padding and

filtering in one step. As of this writing, the Octave-Forge image

package doesn't officially include this function, but it is there in

the source repository now, meaning that it will probably appear in the

next version of that package. I actually wrote my own before I found

this one. You can grab the official one

here:

imfilter.m

With this new function, we can filter with the Gaussian and save like

this. Notice the flipping of the first two arguments

from filter2, as well as the lack of converting

to uint8.

gauss_m = imfilter(m, f, "symmetric");

imwrite("gauss.png", gauss_m);

imfilter() will also handle the 3-layer color images

seamlessly. Without it, you would need to run filter2()

on each layer separately.

So that is just about all there is. fspecial() has many

more filters available including motion

blur,

unsharp, and edge detection. For example,

the Sobel edge

detector,

octave:25> fspecial("sobel")

ans =

1 2 1

0 0 0

-1 -2 -1

It is good at detecting edges in one direction. We can rotate this

each way to detect edges all over the image.

mf = uint8(zeros(size(m)));

for i = 0:3

mf += imfilter(m, rot90(fspecial("sobel"), i));

end

imshow(mf)

Happy Hacking with Octave!