nullprogram.com/blog/2011/06/13/

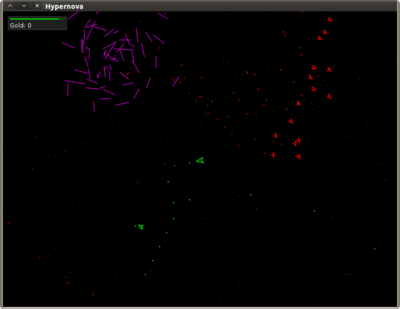

In my free time I’ve been working on an unannounced line-art space

shooter game called Hypernova. It looks a little like Asteroids, but

the screen doesn’t wrap around at all. Space is infinite, and there will

be all sorts of things going on out there. Quests, loot, ship upgrades

and enhancements, hirelings.

It will be using no bitmapped images. All the graphics are vector images

described by text files. I was originally intending to follow the same

path with sound effects, and rely mostly on MIDI. However, I quickly

found out that many computers have no MIDI support at all.

One of the early challenges was a nice starfield background. It has

several constraints:

- Can’t use any bitmapped images.

- Must work over practically infinite space.

- I must be able to resize the display

- Must be fast.

And in addition, there are some unnecessary, but desirable, properties,

-

When leaving a particular location and returning, I’d like to see the

same starfield pattern again.

-

At the same time, I never want to see that same pattern at a different

position.

When I was a kid I created the effect as a project, but it didn’t have

the both the desired properties above. It’s also the method I found over

and over when searching the Internet. There is an array of stars. Star

positions are translated as the camera moves. If a star ever exits the

display, replace it at a random position on the edge of the screen. To

create a parallax effect, each star’s translation is scaled by a unique

random factor.

However, there’s another algorithm I like much better, and it has both

the desirable properties. Space is broken up into a grid of square

tiles. To determine the star pattern in any given tile, hash the tile’s

position, and use the hash output to generate a few positions within the

tiles, which is where stars are drawn. To create a parallax effect,

perform it in different layers at different scales.

Here’s what it looks like in the game,

Hypernova is written in Java, with Clojure as a scripting language, so

the starfield drawing function looks like this.

public static final int STAR_SEED = 0x9d2c5680;

public static final int STAR_TILE_SIZE = 256;

public void drawStars(Graphics2D g, int xoff, int yoff, int starscale) {

int size = STAR_TILE_SIZE / starscale;

int w = getWidth();

int h = getHeight();

/* Top-left tile's top-left position. */

int sx = ((xoff - w/2) / size) * size - size;

int sy = ((yoff - h/2) / size) * size - size;

/* Draw each tile currently in view. */

for (int i = sx; i <= w + sx + size * 3; i += size) {

for (int j = sy; j <= h + sy + size * 3; j += size) {

int hash = mix(STAR_SEED, i, j);

for (int n = 0; n < 3; n++) {

int px = (hash % size) + (i - xoff);

hash >>= 3;

int py = (hash % size) + (j - yoff);

hash >>= 3;

g.drawLine(px, py, px, py);

}

}

}

}

Assuming the origin is in the center of the display, it iterates over

each tile currently covered by the display. Positions are created by

looking at the first couple bits of the hash for X, shift a few off, and

looking at the first few bits again for Y. Repeat until we run out of

bits. It’s called with different starscales, back to front (darker to

lighter), to create layers.

The STAR_SEED is just a Mersenne prime from the Mersenne Twister PRNG.

It probably doesn’t matter much what you choose for the seed, but

changing it by a single bit will drastically alter the starfield.

As far as I know, Java comes with no decent 32-bit (int) hash functions,

which is really one of the biggest roadblocks in implementing effective

hashCodes()s. Fortunately, I found an excellent hash function, Robert

Jenkins’ 96 bit Mix

Function, to do the

trick.

/** Robert Jenkins' 96 bit Mix Function. */

private static int mix(int a, int b, int c) {

a=a-b; a=a-c; a=a^(c >>> 13);

b=b-c; b=b-a; b=b^(a << 8);

c=c-a; c=c-b; c=c^(b >>> 13);

a=a-b; a=a-c; a=a^(c >>> 12);

b=b-c; b=b-a; b=b^(a << 16);

c=c-a; c=c-b; c=c^(b >>> 5);

a=a-b; a=a-c; a=a^(c >>> 3);

b=b-c; b=b-a; b=b^(a << 10);

c=c-a; c=c-b; c=c^(b >>> 15);

return c;

}