nullprogram.com/blog/2014/09/18/

The challenge: As quickly as possible, find all occurrences of a

given sequence of digits in the first one billion digits of pi. You

don’t have to compute pi yourself for this challenge. For

example, “141592653” appears 4 times: at positions 1, 427,238,911,

570,434,346, and 678,096,434.

To my surprise, this turned out to be harder than I expected. A

straightforward scan with Boyer-Moore-Horspool across the

entire text file is already pretty fast. On modern, COTS hardware it

takes about 6 seconds. Comparing bytes is cheap and it’s largely an

I/O-bound problem. This means building fancy indexes tends to make it

slower because it’s more I/O demanding.

The challenge was inspired by The Pi-Search Page, which

offers a search on the first 200 million digits. There’s also a little

write-up about how their pi search works. I wanted to try to invent my

own solution. I did eventually come up with something that worked,

which can be found here. It’s written in plain old C.

You might want to give the challenge a shot on your own before

continuing!

SQLite

The first thing I tried was SQLite. I thought an index (B-tree) over

fixed-length substrings would be efficient. A LIKE condition with a

right-hand wildcard is sargable and would work well with the

index. Here’s the schema I tried.

CREATE TABLE digits

(position INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, sequence TEXT NOT NULL)

There will be 1 row for each position, i.e. 1 billion rows. Using

INTEGER PRIMARY KEY means position will be used directly for row

IDs, saving some database space.

After the data has been inserted by sliding a window along pi, I

build an index. It’s better to build an index after data is in the

database than before.

CREATE INDEX sequence_index ON digits (sequence, position)

This takes several hours to complete. When it’s done the database is

a whopping 60GB! Remember I said that this is very much an I/O-bound

problem? I wasn’t kidding. This doesn’t work well at all. Here’s the

a search for the example sequence.

SELECT position, sequence FROM digits

WHERE sequence LIKE '141592653%'

You get your answers after about 15 minutes of hammering on the disk.

Sometime later I realized that up to 18-digits sequences could be

encoded into an integer, so that TEXT column could be a much simpler

INTEGER. Unfortunately this doesn’t really improve anything. I also

tried this in PostgreSQL but it was even worse. I gave up after 24

hours of waiting on it. These databases are not built for such long,

skinny tables, at least not without beefy hardware.

Offset DB

A couple weeks later I had another idea. A query is just a sequence of

digits, so it can be trivially converted into a unique number. As

before, pick a fixed length for sequences (n) for the index and an

appropriate stride. The database would be one big file. To look up a

sequence, treat that sequence as an offset into the database and seek

into the database file to that offset times the stride. The total size

of the database is 10^n * stride.

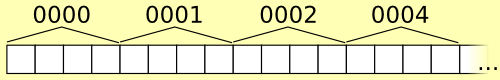

In this quick and dirty illustration, n=4 and stride=4 (far too small

for that n).

For example, if the fixed-length for sequences is 6 and the stride is

4,000 bytes, looking up “141592” is just a matter of seeking to byte

141,592 * 4,000 and reading in positions until some sort of

sentinel. The stride must be long enough to store all the positions

for any indexed sequence.

For this purpose, the digits of pi are practically random numbers. The

good news is that it means a fixed stride will work well. Any

particular sequence appears just as often as any other. The chance a

specific n-length sequence begins at a specific position is 1 /

10^n. There are 1 billion positions, so a particular sequence will

have 1e9 / 10^n positions associated with it, which is a good place

to start for picking a stride.

The bad news is that building the index means jumping around the

database essentially at random for each write. This will break any

sort of cache between the program and the hard drive. It’s incredibly

slow, even mmap()ed. The workaround is to either do it entirely in RAM

(needs at least 6GB of RAM for 1 billion digits!) or to build it up

over many passes. I didn’t try it on an SSD but maybe the random

access is more tolerable there.

Adding an Index

Doing all the work in memory makes it easier to improve the database

format anyway. It can be broken into an index section and a tables

section. Instead of a fixed stride for the data, front-load the

database with a similar index that points to the section (table) of

the database file that holds that sequence’s pi positions. Each of the

10^n positions gets a single integer in the index at the front of

the file. Looking up the positions for a sequence means parsing the

sequence as a number, seeking to that offset into the beginning of the

database, reading in another offset integer, and then seeking to that

new offset. Now the database is compact and there are no concerns

about stride.

No sentinel mark is needed either. The tables are concatenated in

order in the table part of the database. To determine where to stop,

take a peek at the next sequence’s start offset in the index. Its

table immediately follows, so this doubles as an end offset. For

convenience, one final integer in the index will point just beyond the

end of the database, so the last sequence (99999…) doesn’t require

special handling.

Searching Shorter and Longer

If the database built for fixed length sequences, how is a sequence of

a different length searched? The two cases, shorter and longer, are

handled differently.

If the sequence is shorter, fill in the remaining digits, …000 to

…999, and look up each sequence. For example, if n=6 and we’re

searching for “1415”, get all the positions for “141500”, “141501”,

“141502”, …, “141599” and concatenate them. Fortunately the database

already has them stored this way! Look up the offsets for “141500” and

“141600” and grab everything in between. The downside is that the pi

positions are only partially sorted, so they may require sorting

before presenting to the user.

If the sequence is longer, the original digits file will be needed.

Get the table for the subsequence fixed-length prefix, then seek into

the digits file checking each of the pi positions for a full match.

This requires lots of extra seeking, but a long sequence will

naturally have fewer positions to test. For example, if n=7 and we’re

looking for “141592653”, look up the “1415926” table in the database

and check each of its 106 positions.

With this database searches are only a few milliseconds (though very

much subject to cache misses). Here’s my program in action, from the

repository linked above.

$ time ./pipattern 141592653

1: 14159265358979323

427238911: 14159265303126685

570434346: 14159265337906537

678096434: 14159265360713718

real 0m0.004s

user 0m0.000s

sys 0m0.000s

I call that challenge completed!