nullprogram.com/blog/2014/11/22/

When I was a kid I spent some time playing a top-down, 2D,

puzzle/action, 1993, MS-DOS game called God of Thunder. It

came on a shareware CD, now long lost, called Games People Play. A

couple decades later I was recently reminded of the game and decided

to dig it up and play it again. It’s not quite as exciting

as I remember it — nostalgia really warps perception — but it’s

still an interesting game nonetheless.

That got me thinking about how difficult it might be to modify (“mod”)

the game to add my own levels and puzzles. It’s a tiny game, so there

aren’t many assets to reverse engineer. Unpacked, the game just

barely fits on a 1.44 MB high density floppy disk. That was probably

one of the game’s primary design constraints. It also means it’s

almost certainly employing some sort of home-brew compression

algorithm in order to fit more content. I find these sorts of things

absolutely interesting and delightful.

You see, back in those old days, compression wasn’t really a “solved”

problem like it is today. They had to design and implement their own

algorithms, with varying degrees of success. Today if you

need compression for a project, you just grab zlib. Released

in 1995, it implements the most widely used compression algorithm

today, DEFLATE, with a tidy, in-memory API. zlib is well-tested,

thoroughly optimized, and sits in a nearly-perfect sweet spot between

compression ratio and performance. There’s even an embeddable

version. Since spinning platters are so slow compared to CPUs,

compression is likely to speed up an application simply because fewer

bytes need to go to and from the disk. Today it’s less about saving

storage space and more about reducing input/output demands.

Fortunately for me, someone has already reversed engineered

most of the God of Thunder assets. It uses its own flavor of

Lempel-Ziv-Storer-Szymanski (LZSS), which itself is derived

from LZ77, one of the algorithms used in DEFLATE. The original LZSS

paper focuses purely on the math, describing the algorithm in terms of

symbols with no concern for how it’s actually serialized into bits.

Those specific details were decided by the game’s developers, and

that’s what I’ll be describing below.

As an adult I’m finding the God of Thunder asset formats to be more

interesting than the game itself. It’s a better puzzle! I really

enjoy studying the file formats of various applications,

especially older ones that didn’t have modern standards to build on.

Usually lots of thought and engineering goes into the design these

formats — and, too often, not enough thought goes into it. The

format’s specifics reveal insights into the internal workings of the

application, sometimes exposing unanticipated failure modes. Prying

apart odd, proprietary formats (i.e. “data reduction”) is probably my

favorite kind of work at my day job, and it comes up fairly often.

God of Thunder LZSS Definition

An LZSS compression stream is made up of two kinds of chunks: literals

and back references. A literal chunk is passed through to the output

buffer unchanged. A reference chunk is a pair of numbers: a length and

an offset backwards into the output buffer. Only a single bit is

needed for each chunk to identify its type.

To avoid any sort of complicated and slow bit wrangling, the God of

Thunder developers (or whoever inspired them) came up with the smart

idea to stage 8 of these bits up at once as a single byte, a “control”

byte. Since literal chunks are 1 byte and reference chunks are 2

bytes, everything falls onto clean byte boundaries. Every group of 8

chunks is prefixed with one of these control bytes, and so every LZSS

compression stream begins with a control byte. The least significant

bit controls the 1st chunk in the group and the most significant bit

controls the 8th chunk. A 1 denotes a literal and a 0 denotes a

reference.

So, for example, a control byte of 0xff means to pass through

unchanged the next 8 bytes of the compression stream. This would be

the least efficient compression scenario, because the “compressed”

stream is 112.5% (9/8) bigger than the uncompressed stream. Gains come

entirely from the back references.

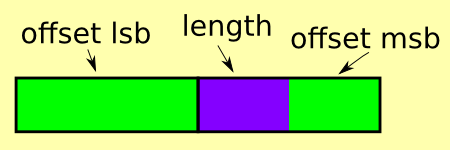

A back reference is two bytes little endian (this was in MS-DOS

running on x86), the lower 12 bits are the offset and the upper 4 bits

are the length, minus 2. That is, you read the 4 length bits and

add 2. This is because it doesn’t make any sense to reference a length

shorter than 2: a literal chunk would be shorter. The offset doesn’t

have anything added to it. This was a design mistake since an offset

of 0 doesn’t make any sense. It refers to a byte just outside the

output buffer. It should have been stored as the offset minus 1.

A 12-bit offset means up to a 4kB sliding window of output may be

referenced at any time. A 4-bit length, plus two, means up to 17 bytes

may be copied in a single back reference. Compared to other

compression algorithms, this is rather short.

It’s important to note that the length is allowed to extend beyond the

output buffer (offset < length). The bytes are, in effect, copied one

at a time into the output and may potentially be reused within the

same operation (like the opposite of memmove). An offset of

1 and a length of 10 means “repeat the last output byte 10 times.”

That’s the entire format! It’s extremely simple but reasonably

effective for the game’s assets.

Worst Case and Best Case

In the worst case, such as compressing random data, the compression

stream will be at most 112.5% (9/8) bigger than the uncompressed

stream.

In the best case, such as a long string of zeros, the compressed

stream will be, at minimum, 12.5% (1/8) the size of the decompressed

stream. Think about it this way: imagine every chunk is a reference of

maximum length. That’s 1 control byte plus 16 (8 * 2) reference

bytes, for a total of 17 compressed bytes. This emits 17 * 8

decompressed bytes, 17 being the maximum length from 8 chunks.

Conveniently those two 17s cancel, leaving a factor of 8 for the best

case.

LZSS End of Stream

If you’re paying really close attention, you may have noticed that

by grouping 8 control bits at a time, the length of the input stream

is, strictly speaking, constrained to certain lengths. What if, during

compression, the input stream stream comes up short of exactly those 8

chunks? As is, there’s no way to communicate a premature end to the

stream. There are three ways around this using a small amount of

metadata, each differing in robustness.

-

Keep track of the size of the decompressed data. When that many

bytes have been emitted, halt. This is how God of Thunder handles

it. A small validation check could be performed here. The output

stream should always end between chunks, not in the middle of a

chunk (i.e. in the middle of copying a back reference). Some of the

bits in the control byte may contain arbitrary data that doesn’t

effect the output, which is a concern when hashing compressed data.

My suggestion: require the unused control bits to be 0, which

allows for an additional validation check. The output stream should

never end just short of a literal chunk.

-

Keep track of the size of the compressed data. Halt when no more

chunks are encountered. A similar, weaker validation check can be

performed here: the input stream should never stop between two

bytes of a reference. It’s weaker because it’s less sensitive to

corruption, making it harder to detect. The same unused control bit

padding situation applies here.

-

Use an out-of-band end marker (EOF). This is very similar to

keeping track of the input size (the filesystem is doing it), but

has the weakest validation of all. The stream could be accidentally

truncated at any point between chunks, which is undetectable. This

makes it the least sensitive to corruption.

An LZSS Quine

After spending some time playing around with this format, I thought

about what it would take to make an LZSS quine. That is, find an

LZSS compressed stream that decompresses to itself. It’s been done

for DEFLATE, which I imagine is a much harder problem. There are zip

files containing exact copies of themselves, recursively. I’m

pretty confident it’s never been done for this exact compression

format, simply because it’s so specific to this old MS-DOS game.

I haven’t figured it out yet, so you won’t find the solution here.

This, dear readers, is my challenge to you! Using the format

described above, craft an LZSS quine. LZSS doesn’t have no-op chunks

(i.e. length = 0), which makes this harder than it would otherwise be.

It may not even be possible, which, in that case, your challenge is to

prove it!

So far I’ve determined that it begins with at least 4kB of 0xff. Why

is this? First, as I mentioned, all compression streams begin with a

control byte. Second, no references can be made until at least one

literal byte has been passed, so the first bit (LSB) of the first byte

is a 1, and the second byte is exactly the same as the first byte. So

the first two bytes are xxxxxx1, with the x being “don’t care (yet).”

If the next chunk is a back reference, those first two bytes become

xxxxxx01. It could only reference that one byte (so offset = 1), and

the length would need to be at least two, ensuring at least the first

three bytes of output all have that same pattern. However, on the most

significant byte of the reference chunk, this conflicts with having an

offset of 1 because the 9th bit of the offset is set to 1, forcing the

offset to an invalid 257 bytes. Therefore, the second chunk must be a

literal.

This pattern continues until the first eight chunks are all literals,

which means the quine begins with at least 9 0xff bytes. Going on,

this also means the first back reference is going to be 0xffff

(offset = 4095, length = 17), so the sliding window needs to be filled

enough to make that a offset valid. References would then be used to

“catch up” with the compression stream, then some magic is needed to

finish off the stream.

That’s where I’m stuck.