nullprogram.com/blog/2012/04/23/

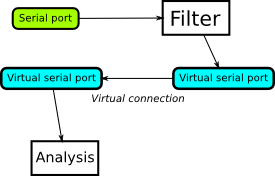

My dad recently had an interesting problem at work related to serial

ports. Since I use serial ports at work, he asked me for advice. They

have third-party software which reads and analyzes sensor data from

the serial port. It’s the only method this program has of inputting a

stream of data and they’re unable to patch it. Unfortunately, they

have another piece of software that needs to massage the data before

this final program gets it. The data needs to be intercepted coming on

the serial port somehow.

The solution they were aiming for was to create a pair of virtual

serial ports. The filter software would read data in on the real

serial port, output the filtered data into a virtual serial port which

would be virtually connected to a second virtual serial port. The

analysis software would then read from this second serial port. They

couldn’t figure out how to set this up, short of buying a couple of

USB/serial port adapters and plugging them into each other.

It turns out this is very easy to do on Unix-like systems. POSIX

defines two functions, posix_openpt(3) and ptsname(3). The first

one creates a pseudo-terminal — a virtual serial port — and returns

a “master” file descriptor used to talk to it. The second provides

the name of the pseudo-terminal device on the filesystem, usually

named something like /dev/pts/5.

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

int main()

{

int fd = posix_openpt(O_RDWR | O_NOCTTY);

printf("%s\n", ptsname(fd));

/* ... read and write to fd ... */

return 0;

}

The printed device name can be opened by software that’s expecting to

access a serial port, such as

minicom, and it can be

communicated with as if by a pipe. This could be useful in testing a

program’s serial port communication logic virtually.

The reason for the unusually long name is because the function wasn’t

added to POSIX until 1998 (Unix98). They were probably afraid of name

collisions with software already using openpt() as a function

name. The GNU C Library provides an extension getpt(3), which is

just shorthand for the above.

Pseudo-terminal functionality was available much earlier, of

course. It could be done through the poorly designed openpty(3),

added in BSD Unix.

int openpty(int *amaster, int *aslave, char *name,

const struct termios *termp,

const struct winsize *winp);

It accepts NULL for the last three arguments, allowing the user to

ignore them. What makes it so bad is that string name. The user

would pass it a chunk of allocated space and hope it was long enough

for the file name. If not, openpty() would overwrite the end of the

string and trash some memory. It’s highly unlikely to ever exceed

something like 32 bytes, but it’s still a correctness problem.

The newer ptsname() is only slightly better however. It returns a

string that doesn’t need to be free()d, because it’s static

memory. However, that means the function is not re-entrant; it has

issues in multi-threaded programs, since that string could be trashed

at any instant by another call to ptsname(). Consider this case,

int fd0 = getpt();

int fd1 = getpt();

printf("%s %s\n", ptsname(fd0), ptsname(fd1));

ptsname() will be returning the same char * pointer each time it’s

called, merely filling the pointed-to space before returning. Rather

than printing two different device filenames, the above would print

the same filename twice. The GNU C Library provides an extension to

correct this flaw, as ptsname_r(), where the user provides the

memory as before but also indicates its maximum size.

To make a one-way virtual connection between our pseudo-terminals,

create two of them and do the typical buffer thing between the file

descriptors (for succinctness, no checking for errors),

while (1) {

char buffer;

int in = read(pt0, &buffer, 1);

write(pt1, &buffer, in);

}

Making a two-way connection would require the use of threads or

select(2), but it wouldn’t be much more complicated.

While all this was new and interesting to me, it didn’t help my dad at

all because they’re using Windows. These functions don’t exist there

and creating virtual serial ports is a highly non-trivial,

less-interesting process. Buying the two adapters and connecting them

together is my recommended solution for Windows.