nullprogram.com/blog/2014/06/01/

I recently got an itch to play around with Voronoi diagrams.

It’s a diagram that divides a space into regions composed of points

closest to one of a set of seed points. There are a couple of

algorithms for computing a Voronoi diagram: Bowyer-Watson and Fortune.

These are complicated and difficult to implement.

However, if we’re interested only in rendering a Voronoi diagram as

a bitmap, there’s a trivial brute for algorithm. For every pixel of

output, determine the closest seed vertex and color that pixel

appropriately. It’s slow, especially as the number of seed vertices

goes up, but it works perfectly and it’s dead simple!

Does this strategy seem familiar? It sure sounds a lot like an OpenGL

fragment shader! With a shader, I can push the workload off to the

GPU, which is intended for this sort of work. Here’s basically what it

looks like.

/* voronoi.frag */

uniform vec2 seeds[32];

uniform vec3 colors[32];

void main() {

float dist = distance(seeds[0], gl_FragCoord.xy);

vec3 color = colors[0];

for (int i = 1; i < 32; i++) {

float current = distance(seeds[i], gl_FragCoord.xy);

if (current < dist) {

color = colors[i];

dist = current;

}

}

gl_FragColor = vec4(color, 1.0);

}

If you have a WebGL-enabled browser, you can see the results for

yourself here. Now, as I’ll explain below, what you see here isn’t

really this shader, but the result looks identical. There are two

different WebGL implementations included, but only the smarter one is

active. (There’s also a really slow HTML5 canvas fallback.)

You can click and drag points around the diagram with your mouse. You

can add and remove points with left and right clicks. And if you press

the “a” key, the seed points will go for a random walk, animating the

whole diagram. Here’s a (HTML5) video showing it off.

Unfortunately, there are some serious problems with this approach. It

has to do with passing seed information as uniforms.

-

The number of seed vertices is hardcoded. The shader language

requires uniform arrays to have known lengths at compile-time. If I

want to increase the number of seed vertices, I need to generate,

compile, and link a new shader to replace it. My implementation

actually does this. The number is replaced with a %%MAX%%

template that I fill in using a regular expression before sending

the program off to the GPU.

-

The number of available uniform bindings is very constrained,

even on high-end GPUs: GL_MAX_FRAGMENT_UNIFORM_VECTORS. This

value is allowed to be as small as 16! A typical value on high-end

graphics cards is a mere 221. Each array element counts as a

binding, so our shader may be limited to as few as 8 seed vertices.

Even on nice GPUs, we’re absolutely limited to 110 seed vertices.

An alternative approach might be passing seed and color information

as a texture, but I didn’t try this.

-

There’s no way to bail out of the loop early, at least with

OpenGL ES 2.0 (WebGL) shaders. We can’t break or do any sort of

branching on the loop variable. Even if we only have 4 seed

vertices, we still have to compare against the full count. The GPU

has plenty of time available, so this wouldn’t be a big issue,

except that we need to skip over the “unused” seeds somehow. They

need to be given unreasonable position values. Infinity would be an

unreasonable value (infinitely far away), but GLSL floats aren’t

guaranteed to be able to represent infinity. We can’t even know

what the maximum floating-point value might be. If we pick

something too large, we get an overflow garbage value, such as 0

(!!!) in my experiments.

Because of these limitations, this is not a very good way of going

about computing Voronoi diagrams on a GPU. Fortunately there’s a

much much better approach!

A Smarter Approach

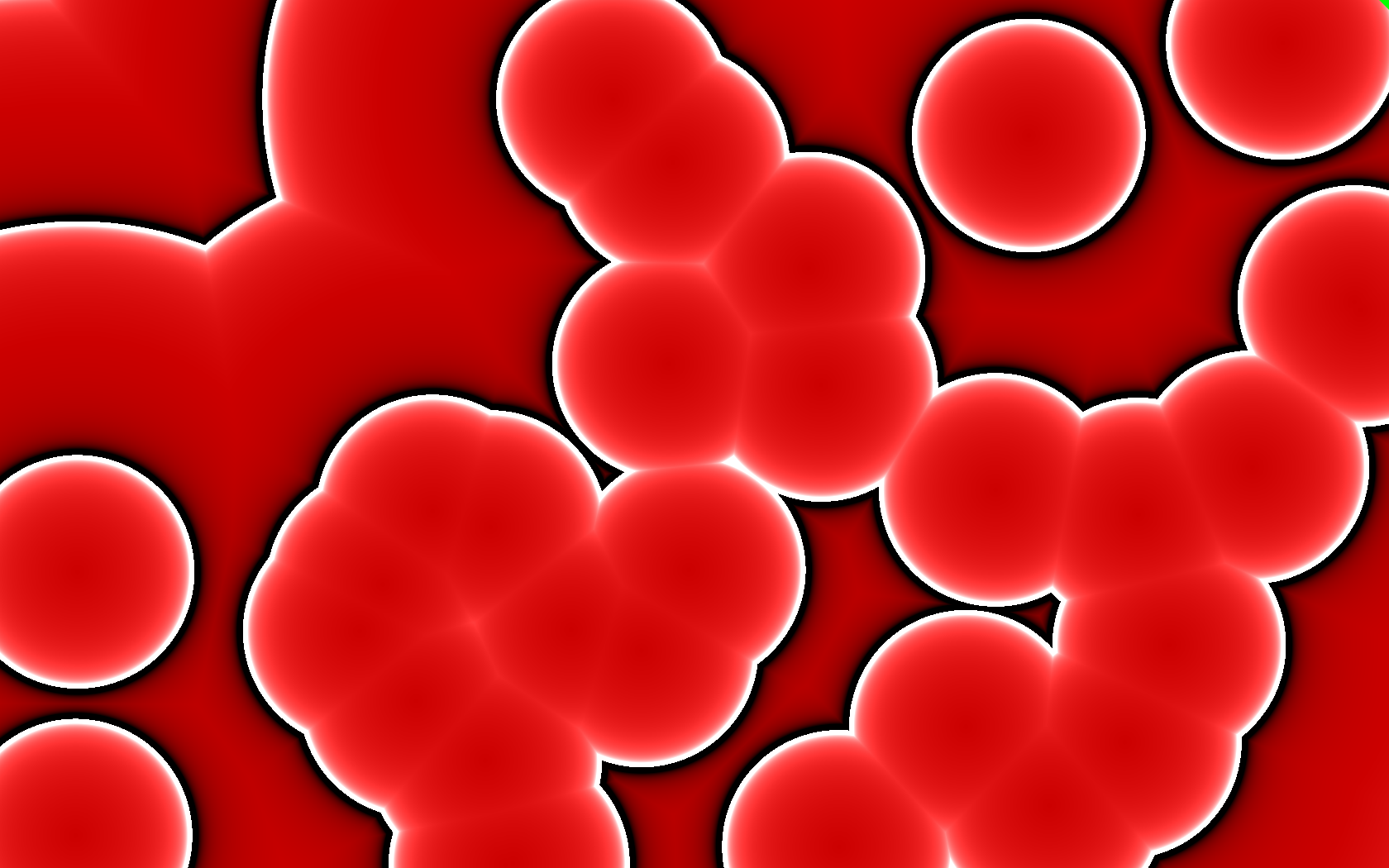

With the above implemented, I was playing around with the fragment

shader, going beyond solid colors. For example, I changed the

shade/color based on distance from the seed vertex. A results of this

was this “blood cell” image, a difference of a couple lines in the

shader.

That’s when it hit me! Render each seed as cone pointed towards the

camera in an orthographic projection, coloring each cone according to

the seed’s color. The Voronoi diagram would work itself out

automatically in the depth buffer. That is, rather than do all this

distance comparison in the shader, let OpenGL do its normal job of

figuring out the scene geometry.

Here’s a video (GIF) I made that demonstrates what I mean.

Not only is this much faster, it’s also far simpler! Rather than being

limited to a hundred or so seed vertices, this version could literally

do millions of them, limited only by the available memory for

attribute buffers.

The Resolution Catch

There’s a catch, though. There’s no way to perfectly represent a cone

in OpenGL. (And if there was, we’d be back at the brute force approach

as above anyway.) The cone must be built out of primitive triangles,

sort of like pizza slices, using GL_TRIANGLE_FAN mode. Here’s a cone

made of 16 triangles.

Unlike the previous brute force approach, this is an approximation

of the Voronoi diagram. The more triangles, the better the

approximation, converging on the precision of the initial brute force

approach. I found that for this project, about 64 triangles was

indistinguishable from brute force.

Instancing to the Rescue

At this point things are looking pretty good. On my desktop, I can

maintain 60 frames-per-second for up to about 500 seed vertices moving

around randomly (“a”). After this, it becomes draw-bound because

each seed vertex requires a separate glDrawArrays() call to OpenGL.

The workaround for this is an OpenGL extension called instancing. The

WebGL extension for instancing is ANGLE_instanced_arrays.

The cone model was already sent to the GPU during initialization, so,

without instancing, the draw loop only has to bind the uniforms and

call draw for each seed. This code uses my Igloo WebGL

library to simplify the API.

var cone = programs.cone.use()

.attrib('cone', buffers.cone, 3);

for (var i = 0; i < seeds.length; i++) {

cone.uniform('color', seeds[i].color)

.uniform('position', seeds[i].position)

.draw(gl.TRIANGLE_FAN, 66); // 64 triangles == 66 verts

}

It’s driving this pair of shaders.

/* cone.vert */

attribute vec3 cone;

uniform vec2 position;

void main() {

gl_Position = vec4(cone.xy + position, cone.z, 1.0);

}

/* cone.frag */

uniform vec3 color;

void main() {

gl_FragColor = vec4(color, 1.0);

}

Instancing works by adjusting how attributes are stepped. Normally the

vertex shader runs once per element, but instead we can ask that some

attributes step once per instance, or even once per multiple

instances. Uniforms are then converted to vertex attribs and the

“loop” runs implicitly on the GPU. The instanced glDrawArrays() call

takes one additional argument: the number of instances to draw.

ext = gl.getExtension("ANGLE_instanced_arrays"); // only once

programs.cone.use()

.attrib('cone', buffers.cone, 3)

.attrib('position', buffers.positions, 2)

.attrib('color', buffers.colors, 3);

/* Tell OpenGL these iterate once (1) per instance. */

ext.vertexAttribDivisorANGLE(cone.vars['position'], 1);

ext.vertexAttribDivisorANGLE(cone.vars['color'], 1);

ext.drawArraysInstancedANGLE(gl.TRIANGLE_FAN, 0, 66, seeds.length);

The ugly ANGLE names are because this is an extension, not part of

WebGL itself. As such, my program will fall back to use multiple draw

calls when the extension is not available. It’s only there for a speed

boost.

Here are the new shaders. Notice the uniforms are gone.

/* cone-instanced.vert */

attribute vec3 cone;

attribute vec2 position;

attribute vec3 color;

varying vec3 vcolor;

void main() {

vcolor = color;

gl_Position = vec4(cone.xy + position, cone.z, 1.0);

}

/* cone-instanced.frag */

varying vec3 vcolor;

void main() {

gl_FragColor = vec4(vcolor, 1.0);

}

On the same machine, the instancing version can do a few thousand seed

vertices (an order of magnitude more) at 60 frames-per-second, after

which it becomes bandwidth saturated. This is because, for the

animation, every vertex position is updated on the GPU on each frame.

At this point it’s overcrowded anyway, so there’s no need to support

more.