nullprogram.com/blog/2014/06/29/

The next project in my GPGPU series is a particle physics

engine that computes the entire physics simulation on the GPU.

Particles are influenced by gravity and will bounce off scene

geometry. This WebGL demo uses a shader feature not strictly required

by the OpenGL ES 2.0 specification, so it may not work on some

platforms, especially mobile devices. It will be discussed later in

the article.

It’s interactive. The mouse cursor is a circular obstacle that the

particles bounce off of, and clicking will place a permanent obstacle

in the simulation. You can paint and draw structures through which the

the particles will flow.

Here’s an HTML5 video of the demo in action, which, out of necessity,

is recorded at 60 frames-per-second and a high bitrate, so it’s pretty

big. Video codecs don’t gracefully handle all these full-screen

particles very well and lower framerates really don’t capture the

effect properly. I also added some appropriate sound that you won’t

hear in the actual demo.

On a modern GPU, it can simulate and draw over 4 million particles

at 60 frames per second. Keep in mind that this is a JavaScript

application, I haven’t really spent time optimizing the shaders, and

it’s living within the constraints of WebGL rather than something more

suitable for general computation, like OpenCL or at least desktop

OpenGL.

Encoding Particle State as Color

Just as with the Game of Life and path finding

projects, simulation state is stored in pairs of textures and the

majority of the work is done by a fragment shader mapped between them

pixel-to-pixel. I won’t repeat myself with the details of setting this

up, so refer to the Game of Life article if you need to see how it

works.

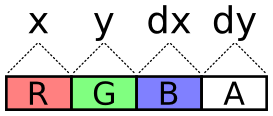

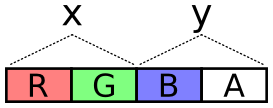

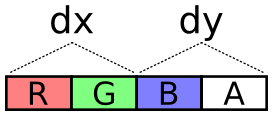

For this simulation, there are four of these textures instead of two:

a pair of position textures and a pair of velocity textures. Why pairs

of textures? There are 4 channels, so every one of these components

(x, y, dx, dy) could be packed into its own color channel. This seems

like the simplest solution.

The problem with this scheme is the lack of precision. With the

R8G8B8A8 internal texture format, each channel is one byte. That’s 256

total possible values. The display area is 800 by 600 pixels, so not

even every position on the display would be possible. Fortunately, two

bytes, for a total of 65,536 values, is plenty for our purposes.

The next problem is how to encode values across these two channels. It

needs to cover negative values (negative velocity) and it should try

to take full advantage of dynamic range, i.e. try to spread usage

across all of those 65,536 values.

To encode a value, multiply the value by a scalar to stretch it over

the encoding’s dynamic range. The scalar is selected so that the

required highest values (the dimensions of the display) are the

highest values of the encoding.

Next, add half the dynamic range to the scaled value. This converts

all negative values into positive values with 0 representing the

lowest value. This representation is called Excess-K. The

downside to this is that clearing the texture (glClearColor) with

transparent black no longer sets the decoded values to 0.

Finally, treat each channel as a digit of a base-256 number. The

OpenGL ES 2.0 shader language has no bitwise operators, so this is

done with plain old division and modulus. I made an encoder and

decoder in both JavaScript and GLSL. JavaScript needs it to write the

initial values and, for debugging purposes, so that it can read back

particle positions.

vec2 encode(float value) {

value = value * scale + OFFSET;

float x = mod(value, BASE);

float y = floor(value / BASE);

return vec2(x, y) / BASE;

}

float decode(vec2 channels) {

return (dot(channels, vec2(BASE, BASE * BASE)) - OFFSET) / scale;

}

And JavaScript. Unlike normalized GLSL values above (0.0-1.0), this

produces one-byte integers (0-255) for packing into typed arrays.

function encode(value, scale) {

var b = Particles.BASE;

value = value * scale + b * b / 2;

var pair = [

Math.floor((value % b) / b * 255),

Math.floor(Math.floor(value / b) / b * 255)

];

return pair;

}

function decode(pair, scale) {

var b = Particles.BASE;

return (((pair[0] / 255) * b +

(pair[1] / 255) * b * b) - b * b / 2) / scale;

}

The fragment shader that updates each particle samples the position

and velocity textures at that particle’s “index”, decodes their

values, operates on them, then encodes them back into a color for

writing to the output texture. Since I’m using WebGL, which lacks

multiple rendering targets (despite having support for gl_FragData),

the fragment shader can only output one color. Position is updated in

one pass and velocity in another as two separate draws. The buffers

are not swapped until after both passes are done, so the velocity

shader (intentionally) doesn’t uses the updated position values.

There’s a limit to the maximum texture size, typically 8,192 or 4,096,

so rather than lay the particles out in a one-dimensional texture, the

texture is kept square. Particles are indexed by two-dimensional

coordinates.

It’s pretty interesting to see the position or velocity textures drawn

directly to the screen rather than the normal display. It’s another

domain through which to view the simulation, and it even helped me

identify some issues that were otherwise hard to see. The output is a

shimmering array of color, but with definite patterns, revealing a lot

about the entropy (or lack thereof) of the system. I’d share a video

of it, but it would be even more impractical to encode than the normal

display. Here are screenshots instead: position, then velocity. The

alpha component is not captured here.

Entropy Conservation

One of the biggest challenges with running a simulation like this on a

GPU is the lack of random values. There’s no rand() function in the

shader language, so the whole thing is deterministic by default. All

entropy comes from the initial texture state filled by the CPU. When

particles clump up and match state, perhaps from flowing together over

an obstacle, it can be difficult to work them back apart since the

simulation handles them identically.

To mitigate this problem, the first rule is to conserve entropy

whenever possible. When a particle falls out of the bottom of the

display, it’s “reset” by moving it back to the top. If this is done by

setting the particle’s Y value to 0, then information is destroyed.

This must be avoided! Particles below the bottom edge of the display

tend to have slightly different Y values, despite exiting during the

same iteration. Instead of resetting to 0, a constant value is added:

the height of the display. The Y values remain different, so these

particles are more likely to follow different routes when bumping into

obstacles.

The next technique I used is to supply a single fresh random value via

a uniform for each iteration This value is added to the position and

velocity of reset particles. The same value is used for all particles

for that particular iteration, so this doesn’t help with overlapping

particles, but it does help to break apart “streams”. These are

clearly-visible lines of particles all following the same path. Each

exits the bottom of the display on a different iteration, so the

random value separates them slightly. Ultimately this stirs in a few

bits of fresh entropy into the simulation on each iteration.

Alternatively, a texture containing random values could be supplied to

the shader. The CPU would have to frequently fill and upload the

texture, plus there’s the issue of choosing where to sample the

texture, itself requiring a random value.

Finally, to deal with particles that have exactly overlapped, the

particle’s unique two-dimensional index is scaled and added to the

position and velocity when resetting, teasing them apart. The random

value’s sign is multiplied by the index to avoid bias in any

particular direction.

To see all this in action in the demo, make a big bowl to capture all

the particles, getting them to flow into a single point. This removes

all entropy from the system. Now clear the obstacles. They’ll all fall

down in a single, tight clump. It will still be somewhat clumped when

resetting at the top, but you’ll see them spraying apart a little bit

(particle indexes being added). These will exit the bottom at slightly

different times, so the random value plays its part to work them apart

even more. After a few rounds, the particles should be pretty evenly

spread again.

The last source of entropy is your mouse. When you move it through the

scene you disturb particles and introduce some noise to the

simulation.

Textures as Vertex Attribute Buffers

This project idea occurred to me while reading the OpenGL ES shader

language specification (PDF). I’d been wanting to do a particle

system, but I was stuck on the problem how to draw the particles. The

texture data representing positions needs to somehow be fed back into

the pipeline as vertices. Normally a buffer texture — a texture

backed by an array buffer — or a pixel buffer object —

asynchronous texture data copying — might be used for this, but WebGL

has none these features. Pulling texture data off the GPU and putting

it all back on as an array buffer on each frame is out of the

question.

However, I came up with a cool technique that’s better than both those

anyway. The shader function texture2D is used to sample a pixel in a

texture. Normally this is used by the fragment shader as part of the

process of computing a color for a pixel. But the shader language

specification mentions that texture2D is available in vertex

shaders, too. That’s when it hit me. The vertex shader itself can

perform the conversion from texture to vertices.

It works by passing the previously-mentioned two-dimensional particle

indexes as the vertex attributes, using them to look up particle

positions from within the vertex shader. The shader would run in

GL_POINTS mode, emitting point sprites. Here’s the abridged version,

attribute vec2 index;

uniform sampler2D positions;

uniform vec2 statesize;

uniform vec2 worldsize;

uniform float size;

// float decode(vec2) { ...

void main() {

vec4 psample = texture2D(positions, index / statesize);

vec2 p = vec2(decode(psample.rg), decode(psample.ba));

gl_Position = vec4(p / worldsize * 2.0 - 1.0, 0, 1);

gl_PointSize = size;

}

The real version also samples the velocity since it modulates the

color (slow moving particles are lighter than fast moving particles).

However, there’s a catch: implementations are allowed to limit the

number of vertex shader texture bindings to 0

(GL_MAX_VERTEX_TEXTURE_IMAGE_UNITS). So technically vertex shaders

must always support texture2D, but they’re not required to support

actually having textures. It’s sort of like food service on an

airplane that doesn’t carry passengers. These platforms don’t support

this technique. So far I’ve only had this problem on some mobile

devices.

Outside of the lack of support by some platforms, this allows every

part of the simulation to stay on the GPU and paves the way for a pure

GPU particle system.

Obstacles

An important observation is that particles do not interact with each

other. This is not an n-body simulation. They do, however, interact

with the rest of the world: they bounce intuitively off those static

circles. This environment is represented by another texture, one

that’s not updated during normal iteration. I call this the obstacle

texture.

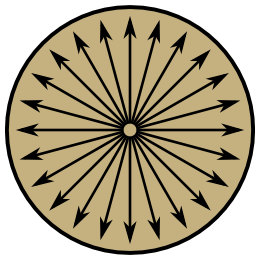

The colors on the obstacle texture are surface normals. That is, each

pixel has a direction to it, a flow directing particles in some

direction. Empty space has a special normal value of (0, 0). This is

not normalized (doesn’t have a length of 1), so it’s an out-of-band

value that has no effect on particles.

(I didn’t realize until I was done how much this looks like the

Greendale Community College flag.)

A particle checks for a collision simply by sampling the obstacle

texture. If it finds a normal at its location, it changes its velocity

using the shader function reflect. This function is normally used

for reflecting light in a 3D scene, but it works equally well for

slow-moving particles. The effect is that particles bounce off the the

circle in a natural way.

Sometimes particles end up on/in an obstacle with a low or zero

velocity. To dislodge these they’re given a little nudge in the

direction of the normal, pushing them away from the obstacle. You’ll

see this on slopes where slow particles jiggle their way down to

freedom like jumping beans.

To make the obstacle texture user-friendly, the actual geometry is

maintained on the CPU side of things in JavaScript. It keeps a list of

these circles and, on updates, redraws the obstacle texture from this

list. This happens, for example, every time you move your mouse on the

screen, providing a moving obstacle. The texture provides

shader-friendly access to the geometry. Two representations for two

purposes.

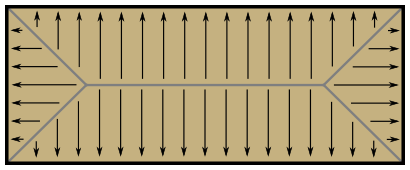

When I started writing this part of the program, I envisioned that

shapes other than circles could place placed, too. For example, solid

rectangles: the normals would look something like this.

So far these are unimplemented.

Future Ideas

I didn’t try it yet, but I wonder if particles could interact with

each other by also drawing themselves onto the obstacles texture. Two

nearby particles would bounce off each other. Perhaps the entire

liquid demo could run on the GPU like this. If I’m imagining

it correctly, particles would gain volume and obstacles forming bowl

shapes would fill up rather than concentrate particles into a single

point.

I think there’s still some more to explore with this project.