nullprogram.com/blog/2015/07/10/

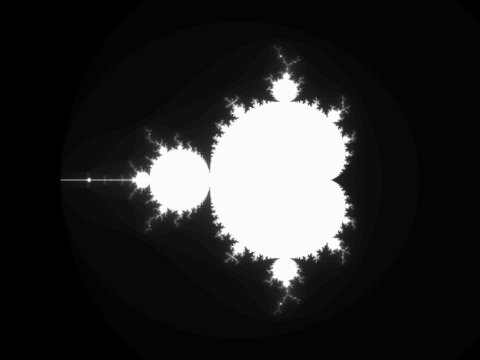

When I started this blog 8 years ago, my first post was about

the Mandelbrot set. Since then, both technology and my own skills have

improved (or so I like to believe!), so I’m going to take another look

at it, this time using three different Single Instruction, Multiple

Data (SIMD) instruction sets: SSE2, AVX, and NEON. The latter two

didn’t exist when the last article was published. In this article I

demonstrate SIMD bringing a 5.8x speedup to a fractal renderer.

If you want to take a look at my code before reading further:

Having multiple CPU cores allows different instructions to operation

on (usually) different data independently. In contrast, under SIMD a

specific operation (single instruction) acts upon several values

(multiple data) at once. It’s another form of parallelization. For

example, with image processing — perhaps the most common use case —

this means multiple pixels could be computed within the same number of

cycles it would normally take to compute just one. SIMD is generally

implemented on CPUs through wide registers: 64, 128, 256, and even 512

bits wide. Values are packed into the register like an array and are

operated on independently, generally with saturation arithmetic

(clamped, non-wrapping).

Rather than hand-code all this in assembly, I’m using yet another

technique I picked up from the always-educational Handmade Hero:

compiler intrinsics. The code is all C, but in place of C’s operators

are pseudo-function calls operating on special SIMD types. These

aren’t actual function calls, they’re intrinsics. The compiler will

emit a specific assembly instruction for each intrinsic, sort of like

an inline function. This is more flexible for mixing with other C

code, the compiler will manage all the registers, and the compiler

will attempt to re-order and interleave instructions to maximize

throughput. It’s a big win!

Some SIMD History

The first widely consumer available SIMD hardware was probably the MMX

instruction set, introduced to 32-bit x86 in 1997. This provided 8

64-bit mm0 - mm7, registers aliasing the older x87 floating

pointer registers, which operated on packed integer values. This was

extended by AMD with its 3DNow! instruction set, adding floating point

instructions.

However, you don’t need to worry about any of that because these both

were superseded by Streaming SIMD Extensions (SSE) in 1999. SSE has

128-bit registers — confusingly named xmm0 - xmm7 — and a much

richer instruction set. SSE has been extended with SSE2 (2001), SSE3

(2004), SSSE3 (2006), SSE4.1 (2007), and SSE4.2 (2008). x86-64 doesn’t

have SSE2 as an extension but instead as a core component of the

architecture (adding xmm8- xmm15), baking it into its ABI.

In 2009, ARM introduced the NEON instruction set as part of ARMv6.

Like SSE, it has 128-bit registers, but its instruction set is more

consistent and uniform. One of its most visible features over SSE is a

stride load parameter making it flexible for a wider variety data

arrangements. NEON is available on your Raspberry Pi, which is

why I’m using it here.

In 2011, Intel and AMD introduced the Advanced Vector Extensions

(AVX) instruction set. Essentially it’s SSE with 256-bit registers,

named ymm0 - ymm15. That means operating on 8 single-precision

floats at once! As of this writing, this extensions is just starting

to become commonplace on desktops and laptops. It also has extensions:

AVX2 (2013) and AVX-512 (2015).

Starting with C

Moving on to the code, in mandel.c you’ll find mandel_basic, a

straight C implementation that produces a monochrome image. Normally I

would post the code here within the article, but it’s 30 lines long

and most of it isn’t of any particular interest.

I didn’t use C99’s complex number support because — continuing to

follow the approach Handmade Hero — I intended to port this code

directly into SIMD intrinsics. It’s much easier to work from a

straight non-SIMD implementation towards one with compiler intrinsics

than coding with compiler intrinsics right away. In fact, I’d say it’s

almost trivial, since I got it right the first attempt on all three.

There’s just one unusual part:

#pragma omp parallel for schedule(dynamic, 1)

for (int y = 0; y < s->height; y++) {

/* ... */

}

This is an Open Multi-Processing (OpenMP) pragma. It’s a higher-level

threading API than POSIX or Win32 threads. OpenMP takes care of all

thread creation, work scheduling, and cleanup. In this case, the for

loop is parallelized such that each row of the image will be scheduled

individually to a thread, with one thread spawned for each CPU core.

This one line saves all the trouble of managing a work queue and such.

I also use it in my SIMD implementations, composing both forms of

parallelization for maximum performance.

I did it in single precision because I really want to exploit SIMD.

Obviously, being half as wide as double precision, twice an many

single precision operands can fit in a SIMD register.

On my wife’s i7-4770 (8 logical cores), it takes 29.9ms to render

one image using the defaults (1440x1080, real{-2.5, 1.5}, imag{-1.5,

1.5}, 256 iterations). I’ll use the same machine for both the SSE2 and

AVX benchmarks.

SSE2 Mandelbrot Set

The first translation I did was SSE2 (mandel_sse2.c). As with just

about any optimization, it’s more complex and harder to read than the

straight version. Again, I won’t post the code here, especially when

this one has doubled to 60 lines long.

Porting to SSE2 (and SIMD in general) is simply a matter of converting

all assignments and arithmetic operators to their equivalent

intrinsics. The Intel Intrinsics Guide is a godsend for this

step. It’s easy to search for specific operations and it tells you

what headers they come from. Notice that there are no C arithmetic

operators until the very end, after the results have been extracted

from SSE and pixels are being written.

There are two new types present in this version, __m128 and

__m128i. These will be mapped to SSE registers by the compiler, sort

of like the old (outdated) C register keyword. One big difference is

that it’s legal to take the address of these values with &, and the

compiler will worry about the store/load operations. The first type is

for floating point values and the second is for integer values. At

first it’s annoying for these to be separate types (the CPU doesn’t

care), but it becomes a set of compiler-checked rails for avoiding

mistakes.

Here’s how assignment was written in the straight C version:

float iter_scale = 1.0f / s->iterations;

And here’s the SSE version. SSE intrinsics are prefixed with _mm,

and the “ps” stands for “packed single-precision.”

__m128 iter_scale = _mm_set_ps1(1.0f / s->iterations);

This sets all four lanes of the register to the same value (a

broadcast). Lanes can also be assigned individually, such as at the

beginning of the innermost loop.

__m128 mx = _mm_set_ps(x + 3, x + 2, x + 1, x + 0);

This next part shows why the SSE2 version is longer. Here’s the

straight C version:

float zr1 = zr * zr - zi * zi + cr;

float zi1 = zr * zi + zr * zi + ci;

zr = zr1;

zi = zi1;

To make it easier to read in the absence of operator syntax, I broke

out the intermediate values. Here’s the same operation across four

different complex values simultaneously. The purpose of these

intrinsics should be easy to guess from their names.

__m128 zr2 = _mm_mul_ps(zr, zr);

__m128 zi2 = _mm_mul_ps(zi, zi);

__m128 zrzi = _mm_mul_ps(zr, zi);

zr = _mm_add_ps(_mm_sub_ps(zr2, zi2), cr);

zi = _mm_add_ps(_mm_add_ps(zrzi, zrzi), ci);

There are a bunch of swizzle instructions added in SSSE3 and beyond

for re-arranging bytes within registers. With those I could eliminate

that last bit of non-SIMD code at the end of the function for packing

pixels. In an earlier version I used them, but since pixel packing

isn’t a hot spot in this code (it’s outside the tight, innermost

loop), it didn’t impact the final performance, so I took it out for

the sake of simplicity.

The running time is now 8.56ms per image, a 3.5x speedup. That’s

close to the theoretical 4x speedup from moving to 4-lane SIMD. That’s

fast enough to render fullscreen at 60FPS.

AVX Mandelbrot Set

With SSE2 explained, there’s not much to say about AVX

(mandel_avx.c). The only difference is the use of __m256,

__m256i, the _mm256 intrinsic prefix, and that this operates on 8

points on the complex plane instead of 4.

It’s interesting that the AVX naming conventions are subtly improved

over SSE. For example, here are the SSE broadcast intrinsics.

_mm_set1_epi8_mm_set1_epi16_mm_set1_epi32_mm_set1_epi64x_mm_set1_pd_mm_set_ps1

Notice the oddball at the end? That’s discrimination against sufferers

of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. This was fixed in AVX’s

broadcast intrinsics:

_mm256_set1_epi8_mm256_set1_epi16_mm256_set1_epi32_mm256_set1_epi64x_mm256_set1_pd_mm256_set1_ps

The running time here is 5.20ms per image, a 1.6x speedup from

SSE2. That’s not too far from the theoretical 2x speedup from using

twice as many lanes. We can render at 60FPS and spend most of the time

waiting around for the next vsync.

NEON Mandelbrot Set

NEON is ARM’s take on SIMD. It’s what you’d find on your phone and

tablet rather than desktop or laptop. NEON behaves much like a

co-processor: NEON instructions are (cheaply) dispatched

asynchronously to their own instruction pipeline, but transferring

data back out of NEON is expensive and will stall the ARM pipeline

until the NEON pipeline catches up.

Going beyond __m128 and __m256, NEON intrinsics have a

type for each of the possible packings. On x86, the old stack-oriented

x87 floating-point instructions are replaced with SSE single-value

(“ss”, “sd”) instructions. On ARM, there’s no reason to use NEON to

operate on single values, so these “packings” don’t exist. Instead

there are half-wide packings. Note the lack of double-precision

support.

float32x2_t, float32x4_tint16x4_t, int16x8_tint32x2_t, int32x4_tint64x1_t, int64x2_tint8x16_t, int8x8_tuint16x4_t, uint16x8_tuint32x2_t, uint32x4_tuint64x1_t, uint64x2_tuint8x16_t, uint8x8_t

Again, the CPU doesn’t really care about any of these types. It’s all

to help the compiler help us. For example, we don’t want to multiply a

float32x4_t and a float32x2_t since it wouldn’t have a meaningful

result.

Otherwise everything is similar (mandel_neon.c). NEON intrinsics are

(less-cautiously) prefixed with v and suffixed with a type (_f32,

_u32, etc.).

The performance on my model Raspberry Pi 2 (900 MHz quad-core ARM

Cortex-A7) is 545ms per frame without NEON and 232ms with NEON, a

2.3x speedup. This isn’t nearly as impressive as SSE2, also at 4

lanes. My implementation almost certainly needs more work, especially

since I know less about ARM than x86.

Compiling with Intrinsics

For the x86 build, I wanted the same binary to have AVX, SSE2, and

plain C versions, selected by a command line switch and feature

availability, so that I could easily compare benchmarks. Without any

special options, gcc and clang will make conservative assumptions

about the CPU features of the target machine. In order to build using

AVX intrinsics, I need the compiler to assume the target has AVX. The

-mavx argument does this.

mandel_avx.o : mandel_avx.c

$(CC) -c $(CFLAGS) -mavx -o $@ $^

mandel_sse2.o : mandel_sse2.c

$(CC) -c $(CFLAGS) -msse2 -o $@ $^

mandel_neon.o : mandel_neon.c

$(CC) -c $(CFLAGS) -mfpu=neon -o $@ $^

All x86-64 CPUs have SSE2 but I included it anyway for clarity. But it

should also enable it for 32-bit x86 builds.

It’s absolutely critical that each is done in a separate translation

unit. Suppose I compiled like so in one big translation unit,

gcc -msse2 -mavx mandel.c mandel_sse2.c mandel_avx.c

The compiler will likely use some AVX instructions outside of the

explicit intrinsics, meaning it’s going to crash on machine without

AVX (“illegal instruction”). The main program needs to be compiled

with AVX disabled. That’s where it will test for AVX before executing

any special instructions.

Feature Testing

Intrinsics are well-supported across different compilers (surprisingly,

even including the late-to-the-party Microsoft). Unfortunately testing

for CPU features differs across compilers. Intel advertises a

_may_i_use_cpu_feature intrinsic, but it’s not supported in either

gcc or clang. gcc has a __builtin_cpu_supports built-in, but it’s

only supported by gcc.

The most portable solution I came up with is cpuid.h (x86 specific).

It’s supported by at least gcc and clang. The clang version of the

header is much better documented, so if you want to read up on how

this works, read that one.

#include <cpuid.h>

static inline int

is_avx_supported(void)

{

unsigned int eax = 0, ebx = 0, ecx = 0, edx = 0;

__get_cpuid(1, &eax, &ebx, &ecx, &edx);

return ecx & bit_AVX ? 1 : 0;

}

And in use:

if (use_avx && is_avx_supported())

mandel_avx(image, &spec);

else if (use_sse2)

mandel_sse2(image, &spec);

else

mandel_basic(image, &spec);

I don’t know how to test for NEON, nor do I have the necessary

hardware to test it, so on ARM assume it’s always available.

Conclusion

Using SIMD intrinsics for the Mandelbrot set was just an exercise to

learn how to use them. Unlike in Handmade Hero, where it makes a 1080p

60FPS software renderer feasible, I don’t have an immediate, practical

use for CPU SIMD, but, like so many similar techniques, I like having

it ready in my toolbelt for the next time an opportunity arises.