nullprogram.com/blog/2016/09/02/

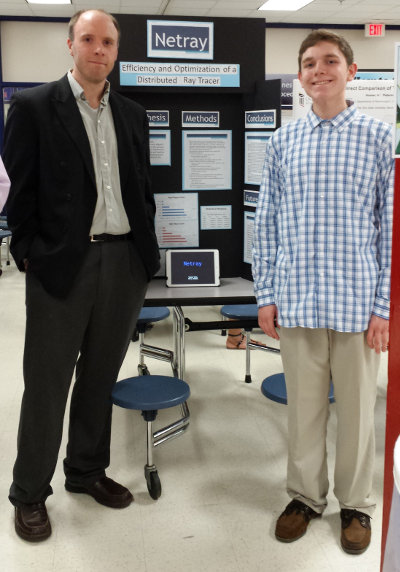

Update June 2019: Dan graduated from college and is now my full-time

colleague.

Over the past two years I’ve been mentoring a high school student, Dan

Kelly, in software development though my workplace mentoring

program. It’s been one of the most rewarding experiences in

my life, far beyond my initial expectations. It didn’t just go well,

it went extraordinarily well. One of my co-workers described the

results as, “the single most successful technical investment I’ve ever

seen made in a person.” Last week the mentorship effectively ended as

he became a college freshman. While it’s fresh in my mind, I’d like to

reflect on how it went and why this arrangement worked so particularly

well for both of us.

Students come into work for a few hours at a time a few days each week

throughout the school year, typically after school. They’re supplied

with their own computer in a mentor-arranged work space. In my case,

Dan sat at a smaller makeshift desk in my office. The schedule is

informal and we were frequently making adjustments as needed.

An indispensable feature is that the students are unpaid. Based on

my observations, the primary reason many other mentorships aren’t

nearly as effective is a failure to correctly leverage this. Some

mentors put students directly to work on an existing, funded project.

This is a mistake. Real world, practical projects are poor learning

environments for beginners. The complexity inhibits development of

the fundamentals, and, from a position of no experience, the

student will have little ability to influence the project, stifling

their motivation.

If being unpaid sounds unfair, remember that these students are coming

in with essentially no programming experience. For several months,

students are time sink. Maybe they fiddled around with Python on their

own, but it probably doesn’t really amount to anything meaningful

(yet).

Being unpaid means students can be put to work on anything, even if

unfunded — even if it’s only for the student’s own benefit. The very

first thing I did with Dan was to walk him through an install of

Debian (wiping the near-useless, corporate Windows image). I wanted

him fully in control of, and responsible for, his own development

environment. I never sat at his keyboard, and all exercises took place

at his computer.

From here I took a bit of an unconventional approach: I decided he was

going to learn from the bottom up, starting with C. There would be no

Fisher-Price-esque graphical programming language (yes, some mentors

actually do this), not even an easier, education-friendly, but

production-ready language like Python. I wanted him to internalize

pointers before trusting him with real work. I showed him how to

invoke gcc, the various types of files involved, how to invoke the

linker, and lent him my hard copy of first edition K&R.

Similarly, I wasn’t going to start him off with some toy text editor.

Like with C, he was going to learn real production tools from the

start. I gave the Emacs run-down and started him on the tutorial

(C-h t). If he changed his mind later after getting more experience,

wanting to use something different, that would be fine.

Once he got the hang of everything so far, I taught him Git and

Magit. Finally we could collaborate.

The first three months were spent on small exercises. He’d learn a

little bit from K&R, describe to me what he learned, and I’d come up

with related exercises, not unlike those on DailyProgrammer, to

cement the concepts. I’d also translate concepts into modern C (e.g.

C99).

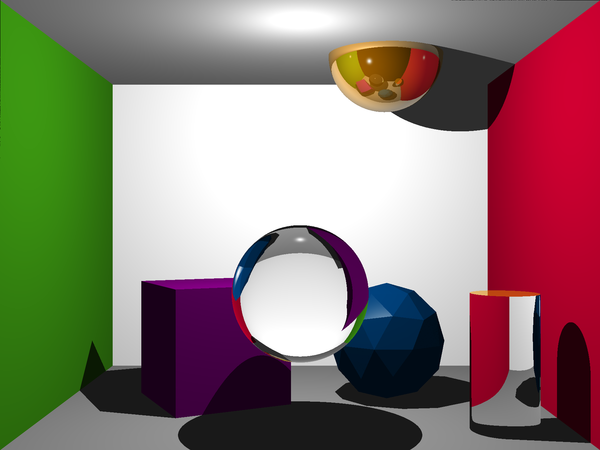

With K&R complete, he was ready to go beyond simple exercises.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to involve him in my own work at the

time. His primary interests included graphics, so we decided on a

multi-threaded, networked multi-processor raytracer.

It was a lot more educational for us both than I expected. I spent a

significant amount of personal time learning graphics well enough to

keep ahead: color spaces, blending, anti-aliasing, brushing up on

linear algebra, optics, lighting models, modeling formats, Blender,

etc. In a few cases I simply learned it from him. It reminds me of a

passage from The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (the namesake of this

blog):

I liked Prof. He would teach anything. Wouldn’t matter that he knew

nothing about it; if pupil wanted it, he would smile and set a

price, locate materials, stay a few lessons ahead. Or barely even if

he found it tough—never pretended to know more than he did. Took

algebra from him and by time we reached cubics I corrected his probs

as often as he did mine—but he charged into each lesson gaily.

I started electronics under him, soon was teaching him. So he

stopped charging and we went along together until he dug up an

engineer willing to daylight for extra money—whereupon we both paid

new teacher and Prof tried to stick with me, thumb-fingered and

slow, but happy to be stretching his mind.

Since this was first and foremost an educational project, I decided we

would use no libraries other than the (POSIX) C standard library. He

would know how nearly every aspect of the program worked. The input

(textures) and output formats were Netpbm PPMs, BMP files, and

YUV4MPEG2 (video), each of which is very easy to read and

write. It loaded 3D models in the easy-to-parse Wavefront .obj

format. It also supported a text rendered overlay, initially

using our own font format and later with fonts in the Glyph Bitmap

Distribution Format — again, easy to parse and use. The text

made it possible to produce demo videos without any additional editing

(see the above video).

After a year on the raytracer, he had implemented most of what he

wanted and I had an opportunity to involve him in my funded research.

By this point he was very capable, quickly paying back his entire

education.

Together we made rapid progress — much more than I could alone. I

can’t go into the specifics, but much of his work was built on lessons

learned from the raytracer, including an OpenGL display and

SIMD-optimized physics engine. I also taught him x86 assembly,

which he applied to co-author a paper, ROP Gadget Prevalence and

Survival under Compiler-based Binary Diversification Schemes

(slides).

To reiterate, an important part of this entire journey was the

influence he had over his own work. He had say on the direction of

each project. Until he started earning a college intern pay

(post-graduation), I had no ability to make him do anything he didn’t

want to do. I could only rely on his motivation. Fortunately what

motivates him is what also motivates me, so to find the framing for

that motivation I only had to imagine myself in his shoes.

An important aspect I hadn’t noticed until the second year was

respect. Most of Dan’s interactions with other co-workers was very

respectful. They listened to what he had to say and treated it with

the same respect as they would a regular, full-time co-worker. I

can’t emphasize how invaluable this is for a student.

I bring this up because there were a handful of interactions that

weren’t so respectful. A few individuals, when discovering his status,

made a jokes (“Hey, where’s my coffee?”) or wouldn’t take his comments

seriously. Please don’t be one of these people.

What’s comes next?

In many ways, Dan is starting college in a stronger position than I

was finishing college. The mentorship was a ton of vocational,

practical experience that doesn’t normally happen in a college course.

However, there’s plenty of computer science theory that I’m not so

great at teaching. For example, he got hands on experience with

practical data structures, but only picked up a shallow understanding

of their analysis (Big O, etc.). College courses will fill those gaps,

and they will be learned more easily with a thorough intuition of

their context.

As he moves on, I’ll be starting all over again with a new student.