nullprogram.com/blog/2018/04/13/

My first exposure to C and C++ was a little over 20 years ago. I

remember it being some version of Borland C++, either 4.x

or 5.x, running on Windows 95. I didn’t have a mentor, so I

did the best I could slowly working through what was probably a poorly

written beginner C++ book, typing out the examples and exercises with

little understanding. Since I didn’t learn much from the experience,

there was a 7 or 8 year gap before I’d revisit C and C++ in college.

I thought it would be interesting to revisit this software, to

reevaluate it from a far more experienced perspective. Keep in mind

that C++ wasn’t even standardized yet, and the most recent C standard

was from 1989. Given this, what was it like to be a professional

software developer using a Borland toolchain on Windows 20 years ago?

Was it miserable, made bearable only by ignorance of how much better

the tooling could be? Or maybe it actually wasn’t so bad, and these

tools are better than I expect?

Ultimately my conclusion is that it’s a little bit of both. There are

some significant capability gaps compared to today, but the core

toolchain itself is actually quite reasonable, especially for the mid

1990s.

The setup

Before getting into the evaluation, let’s discuss how I got it all up

and running. While it’s technically possible to run Windows 95 on a

modern x86-64 machine thanks to the architecture’s extreme backwards

compatibility, it’s more compatible, simpler, and safer to

virtualize it. Most importantly, I can emulate older hardware that

will have better driver support.

Despite that early start in Windows all those years ago, I’m primarily

a Linux user. The premier virtualization solution on Linux these days

is KVM, a kernel module that turns Linux into a hypervisor and

makes efficient use of hardware virtualization extensions.

Unfortunately pre-XP Windows doesn’t work well on KVM, so instead I’m

using QEmu (with KVM disabled), a hardware emulator closely

associated with KVM. Since it doesn’t take advantage of hardware

virtualization extensions, it will be slower. This is fine since my

goal is to emulate slow, 20+ year old hardware anyway.

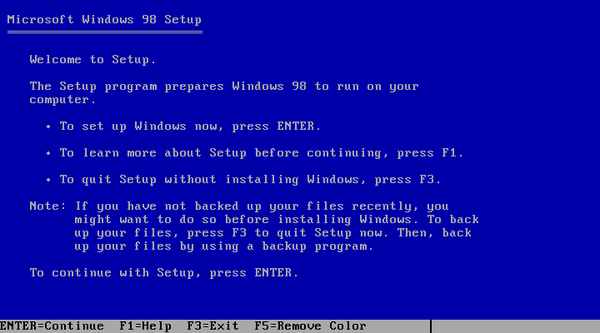

There’s very little practical difference between Windows 95 and

Windows 98. Since Windows 98 runs a lot smoother virtualized, I

decided to go with that instead. This will be perfectly sufficient for

my toolchain evaluation.

Software

To get started, I’ll need an installer for Windows 98. I thought this

would be difficult to find, but there’s a copy available on the

Internet Archive. I don’t know how “legitimate” this is, but it works.

Since it’s running in a virtual machine without network access, I also

don’t really care if this copy is somehow infected with malware.

Internet Archive: Windows 98 Second Edition

Also on the Internet Archive is a complete copy of Borland C++ 5.02,

with the same caveats of legitimacy. It works, which is good enough for

my purposes.

Internet Archive: Borland C++ 5.02

Thank you Internet Archive!

Hardware

I’ve got my software, now to set up the virtualized hardware. First I

create a drive image:

$ qemu-image create -fqcow2 win98.img 8G

I gave it 8GB, which is actually a bit overkill. Giving Windows 98 a

virtual hard drive with modern sizes would probably break the

installer. This sort of issue is a common theme among old software,

where there may be complaints about negative available disk space due

to signed integer overflow.

I decided to give the machine 256MB of memory (-m 256). This is also a

little excessive, but I wanted to be sure memory didn’t limit Borland’s

capabilities. This amount of memory is close to the upper bound, and

going much beyond will likely cause problems with Windows 98.

For the CPU I settled on a Pentium (-cpu pentium). My original goal

was to go a little simpler with a 486 (-cpu 486), but the Windows 98

installer kept crashing when I tried this.

I experimented with different configurations for the network card, but

I couldn’t get anything to work. So I’ve disabled networking (-net

none). The only reason I’d want this is that it would be easier to

move files in and out of the virtual machine.

Finally, here’s how I ran QEmu. The last two lines are only needed when

installing.

$ qemu-system-x86_64 \

-localtime \

-cpu pentium \

-no-acpi \

-no-hpet \

-m 256 \

-hda win98.img \

-soundhw sb16 \

-vga cirrus \

-net none \

-cdrom "Windows 98 Second Edition.iso" \

-boot d

Installation

Installation is just a matter of following the instructions. You’ll

need that product key listed on the Internet Archive site.

That copy of Borland is just a big .zip file. This presents two

problems.

-

Without network access, I’ll need to figure out how to get this

inside the virtual machine.

-

This version of Windows doesn’t come with software to unzip this

file. I’d need to find and install an unzip tool first.

Fortunately I can kill two birds with one stone by converting that .zip

archive into a .iso and mounting it in the virtual machine.

unzip "BORLAND C++.zip"

genisoimage -R -J -o borland.iso "BORLAND C++"

Then in the QEmu console (C-A-2) I attach it:

change ide1-cd0 borland.iso

This little trick of generating .iso files and mounting them is how I

will be moving all the other files into the virtual machine.

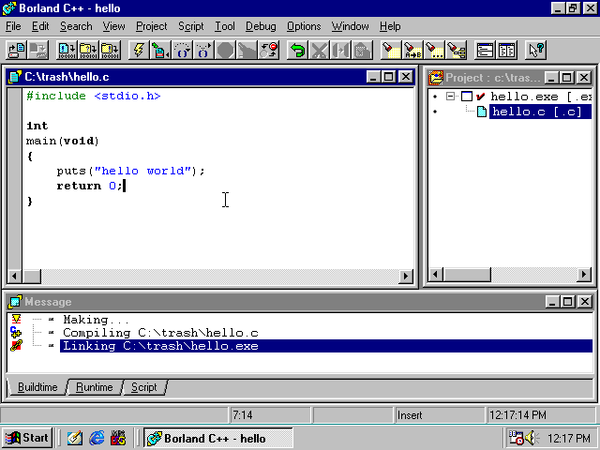

Borland C++

The first thing I did was play around with with Borland IDE. This is

what I would have been using 20 years ago.

Despite being Borland C++, I’m personally most interested in its ANSI

C compiler. As I already pointed out, this software pre-dates C++’s

standardization, and a lot has changed over the past two decades. On the

other hand, C hasn’t really changed all that much. The 1999 update to

the C standard (e.g. “C99”) was big and important, but otherwise little

has changed. The biggest drawback is the lack of “declare anywhere”

variables, including in for-loop initializers. Otherwise it’s the same

as writing C today.

To test drive the IDE, I made a couple of test projects, built and ran

them with different options, and poked around with the debugger. The

debugger is actually pretty decent, especially for the 1990s. It can be

operated via the IDE or standalone, so I could use it without firing up

the IDE and making a project.

The toolchain includes an assembler, and I can inspect the compiler’s

assembly output. To nobody’s surprise this is Intel-flavored assembly,

which is very welcome. Imagining myself as a software developer

in the mid 1990s, this means I can see exactly what the compiler’s doing

as well as write some of the performance sensitive parts in assembly if

necessary.

The built-in editor is the worst part of the IDE, which is unfortunate

since it really spoils the whole experience. It’s easy to jump between

warnings and errors, it has incremental search, and it has good syntax

highlighting. But these are the only positive things I can say about it.

If I had to work with this editor full-time, I’d spend my days pretty

irritated.

Like with the debugger, the Borland people did a good job modularizing

their development tools. As part of the installation process, all of the

Borland command line tools are added to the system PATH (reminder:

this is a single-user system). This includes compiler, linker,

assembler, debugger, and even an incomplete implementation of

make.

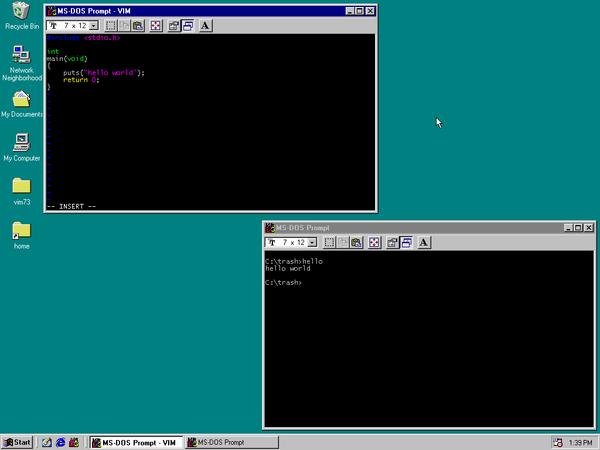

With this, I can essentially pretend the IDE doesn’t exist and replace

that crummy editor with something better: Vim.

The last version of Vim to support MS-DOS and Windows 95/98 is Vim 7.3,

released in 2010. I download those binaries, trim a few things from my

.vimrc, and smuggle it all into my virtual machine via a

virtual CD. I’ve now got a powerful text editor in Windows 98 and my

situation has drastically improved.

Since I hardly use features added since Vim 7.3, this feels right at

home to me. I can invoke the build from Vim, and it

can populate the quickfix list from Borland’s output, so I could

actually be fairly productive in these circumstances! I’m honestly

really impressed with how well this all works together.

At this point I only have two significant annoyances:

-

Borland’s command line tools belong to that category of irritating

programs that print their version banner on every invocation.

There’s not even a command line switch to turn this off. All this

noise is quickly tiresome. The Visual Studio toolchain does

the same thing by default, though it can be turned off (-nologo).

I dislike that some GNU tools also commit this sin, but at least

GNU limits this to interactive programs.

-

The Windows/DOS command shell and console is even worse than it

is today. I didn’t think that was possible. This is back when

it was still genuinely DOS and not just pretending to be (e.g. in

NT). The worst part by far is the lack of command history. There’s

no using the up-arrow to get previous commands. There’s no tab

completion. Forward slash is not a substitute for backslash in

paths. If I wanted to improve my productivity, replacing this

console and shell would be the first priority.

Update: In an email, Aristotle Pagaltzis informed me that Windows 98

comes with DOSKEY.COM, which provides command history for

COMMAND.EXE. Alternatively there’s Enhanced DOSKEY.com, an

open source, alternative implementation that also provides tab

completion for commands and filesnames. This makes the console a lot

more usable (and, honestly, in some ways better than the modern

defaults).

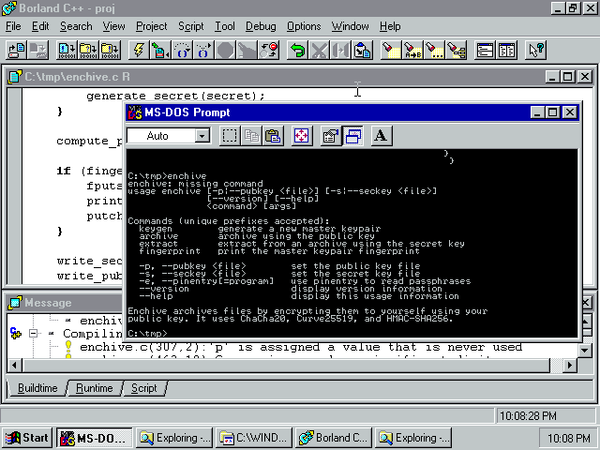

Building Enchive with Borland

Last year I wrote a backup encryption tool called Enchive,

and I still use it regularly. One of my design goals was high

portability since it may be needed to decrypt something important in

the distant future. It should be as bit-rot-proof as

possible. In software, the best way to future-proof is to

past-proof.

If I had a time machine that could send source code back in time, and

I sent Enchive to a competant developer 20 years ago, would they be

able to compile it and run it? If the answer is yes, then that means

Enchive already has 20 years of future-proofing built into it.

To accomplish this, Enchive is 3,300 lines of strict ANSI C,

1989-style, with no dependencies other than the C standard library and

a handful of operating system functions — e.g. functionality not in

the C standard library. In practice, any ANSI C compiler targeting

either POSIX, or Windows 95 or later, should be able to compile it.

My Windows 98 virtual machine includes an ANSI C compiler, and can be

used to simulate this time machine. I generated an “amalgamation” build

(make amalgamation) — essentially a concatenation of all the source

files — and sent this into the virtual machine. Before Borland was able

to compile it, I needed to make three small changes.

First, Enchive includes stdint.h to get fixed-width integers needed

for the encryption routines. This header comes from C99, and C89 has

no equivalent. I anticipated this problem from the beginning and made

it easy for the person performing the build to correct it. This header

is included exactly once, in config.h, and this is placed at the top

of the amalgamation build. The include only needs to be replaced with

a handful of manual typedefs. For Borland that looks like this:

typedef unsigned char uint8_t;

typedef unsigned short uint16_t;

typedef unsigned long uint32_t;

typedef unsigned __int64 uint64_t;

typedef long int32_t;

typedef __int64 int64_t;

#define INT8_C(n) (n)

#define INT16_C(n) (n)

#define INT32_C(n) (n##U)

Second, in more recent versions of Windows, GetFileAttributes() can

return the value INVALID_FILE_ATTRIBUTES. Checking for an error that

cannot happen is harmless, but this value isn’t defined in Borland’s

SDK. I only had to eliminate that check.

Third, the CryptGenRandom() interface isn’t defined in

Borland’s SDK. This is used by Enchive to generate keys. MSDN reports

this function wasn’t available until Windows XP, but it’s definitely

there in Windows 98, exported by ADVAPI32.dll. I’m able to call it,

though it always reports an error. Perhaps it’s been disabled in this

version due to cryptographic export restrictions?

Regardless of what’s wrong, I ripped this out and replaced it with a

fatal error. This version of Enchive can’t generate new keys — unless

derived from a passphrase — nor encrypt files, including the use of a

protection key to encrypt the secret key. However, it can decrypt

files, which is the important part that needs to be future-proofed.

With this three changes — which took me about 10 minutes to sort out —

Enchive builds and runs, and it correctly decrypts files I encrypted on

Linux. So Enchive has at least 20 years of past-proofing! The

screenshot at the top of this article shows it running successfully in

an MS-DOS console window.

What’s wrong? What’s missing?

I mentioned that there were some gaps. The most obvious is the lack of

the standard POSIX utilities, especially a decent shell. I don’t know if

any had been ported to Windows in the mid 1990s. But that could be

solved one way or another without too much trouble, even if it meant

doing some of that myself.

No, the biggest capability I’d miss, and which wouldn’t be easily

obtained, is Git, or a least a decent source control system. I really

don’t want to work without proper source control. Git’s support for

Windows is second tier, and the port to modern Windows is already a

bit of a hack. Getting it to run in Windows 98 would probably be a

challenge, especially if I had to compile it with Borland.

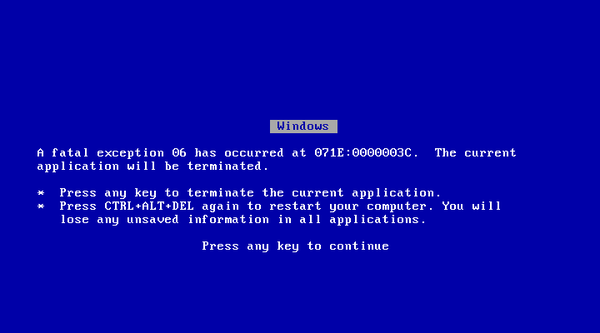

The other major issue is the lack of stability. In this experiment, I’ve

been seeing this screen a lot:

I remember Windows crashing a lot back in those days, and it certainly

had a bad reputation for being unstable, but this is far worse than I

remembered. While the hardware emulator may be somewhat at fault here,

keep in mind that I never installed third party drivers. Most of these

crashes are Windows’ fault. I found I can reliably bring the whole

system down with a single GetProcAddress() call on a system DLL. The

only way I can imagine this instability was so tolerated back then was

general ignorance that computing could be so much better.

I was tempted to write this article in Vim on Windows 98, but all this

crashing made me too nervous. I didn’t want some stupid filesystem

corruption to wipe out my work. Too risky.

A better alternative

If I was stuck working in Windows 98 — or was at least targeting it as a

platform — but had access to a modern tooling ecosystem, could I do

better than Borland? Yes! Programs built by Mingw-w64 can be

run even as far back as Windows 95.

Now, there’s a catch. I thought it would be this simple:

$ i686-w64-mingw32-gcc -Os hello.c

But when I brought the resulting binary into the virtual machine it

crashed when ran it: illegal instruction. Turns out it contained a

conditional move (cmov) which is an instruction not available until

the Pentium Pro (686). The “pentium” emulation is just a 586.

I tried to disable cmov by picking the specific architecture:

$ i686-w64-mingw32-gcc -march=pentium -Os hello.c

This still didn’t work because the statically-linked part of the CRT

contained the cmov. I’d have to recompile that as well.

I could have switched the QEmu options to “upgrade” to a Pentium Pro,

but remember that my goal was really the 486. Fortunately this was easy

to fix: compile my own Mingw-w64 cross-compiler. I’ve done this a number

of times before, so I knew it wouldn’t be difficult.

I could go step by step, but it’s all fairly well documented in the

Mingw-64 “howto-build” document. I used GCC 7.3 (the latest version),

and for the target I picked “i486-w64-mingw32”. When it was done I could

compile binaries on Linux to run in my Windows 98 virtual machine:

$ i486-w64-mingw32-gcc -Os hello.c

This should enable quite a bit of modern software to run inside my

virtual machine if I so wanted. I didn’t actually try this (yet?),

but, to take this concept all the way, I could use this cross-compiler

to cross-compile Mingw-w64 itself to run inside the virtual machine,

directly replacing Borland C++.

And the only thing I’d miss about Borland is its debugger.