nullprogram.com/blog/2025/03/02/

Wavefront OBJ is a line-oriented, text format for 3D geometry. It’s

widely supported by modeling software, easy to parse, and trivial to emit,

much like Netpbm for 2D image data. Poke around hobby 3D graphics

projects and you’re likely to find a bespoke OBJ parser. While typically

only loading their own model data, so robustness doesn’t much matter, they

usually have hard limitations and don’t stand up to fuzz testing.

This article presents a robust, partial OBJ parser in C with no hard-coded

limitations, written from scratch. Like similar articles, it’s not

really about OBJ but demonstrating some techniques you’ve probably never

seen before.

If you’d like to see the ready-to-run full source: objrender.c.

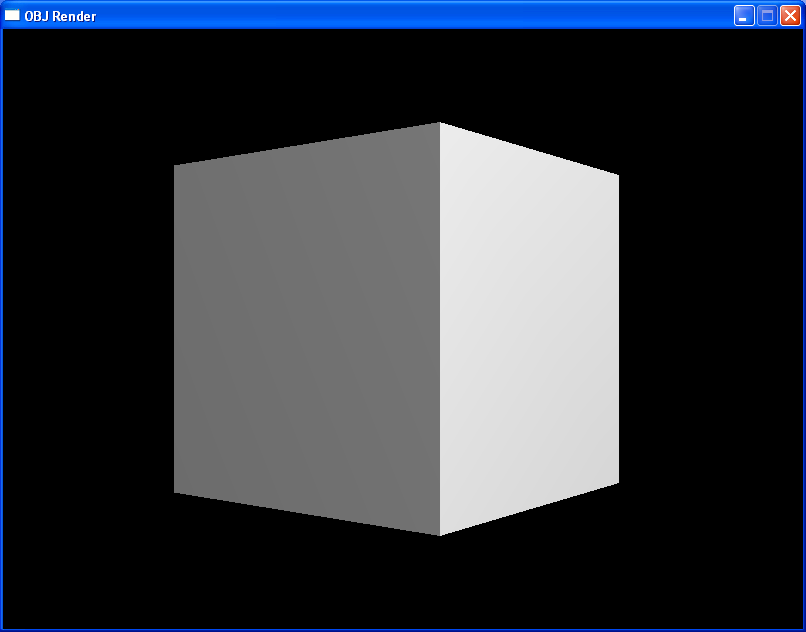

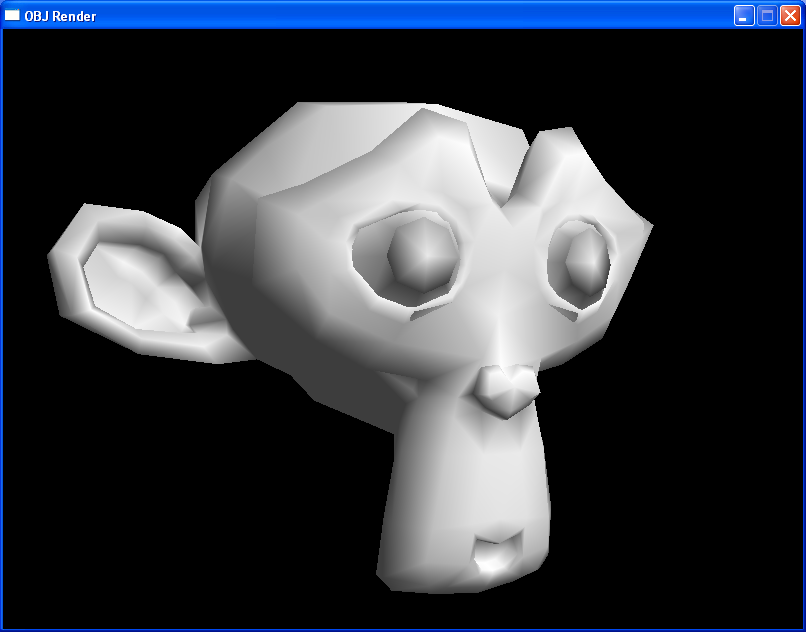

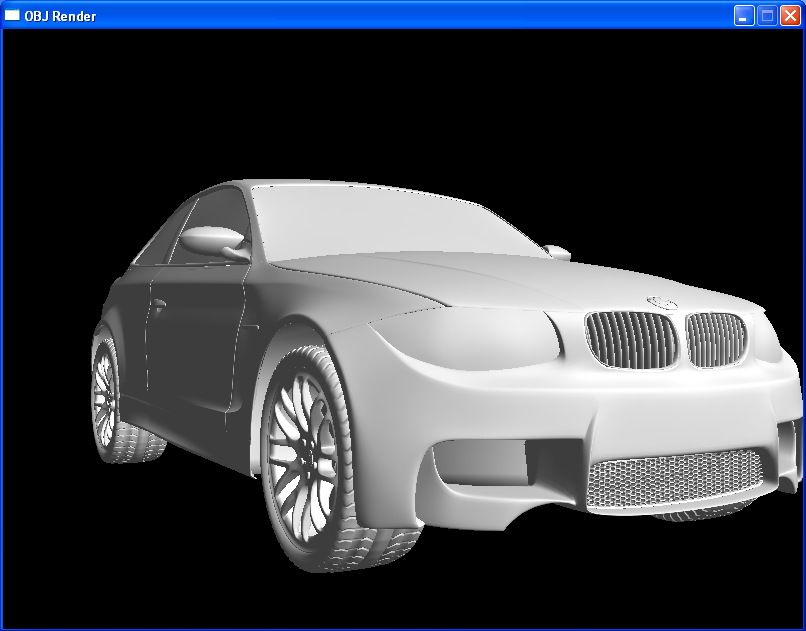

All images are screenshots of this program.

First let’s establish the requirements. By robust I mean no undefined

behavior for any input, valid or invalid; no out of bounds accesses, no

signed overflows. Input is otherwise not validated. Invalid input may load

as valid by chance, which will render as either garbage or nothing. The

behavior will also not vary by locale.

We’re also only worried about vertices, normals, and triangle faces with

normals. In OBJ these are v, vn, and f elements. Normals let us

light the model effectively while checking our work. A cube fitting this

subset of OBJ might look like:

v -1.00 -1.00 -1.00

v -1.00 +1.00 -1.00

v +1.00 +1.00 -1.00

v +1.00 -1.00 -1.00

v -1.00 -1.00 +1.00

v -1.00 +1.00 +1.00

v +1.00 +1.00 +1.00

v +1.00 -1.00 +1.00

vn +1.00 0.00 0.00

vn -1.00 0.00 0.00

vn 0.00 +1.00 0.00

vn 0.00 -1.00 0.00

vn 0.00 0.00 +1.00

vn 0.00 0.00 -1.00

f 3//1 7//1 8//1

f 3//1 8//1 4//1

f 1//2 5//2 6//2

f 1//2 6//2 2//2

f 7//3 3//3 2//3

f 7//3 2//3 6//3

f 4//4 8//4 5//4

f 4//4 5//4 1//4

f 8//5 7//5 6//5

f 8//5 6//5 5//5

f 3//6 4//6 1//6

f 3//6 1//6 2//6

Take note:

- Some fields are separated by more than one space.

- Vertices and normals are fractional (floating point).

- Faces use 1-indexing instead of 0-indexing.

- Faces in this model lack a texture index, hence

// (empty).

Inputs may have other data, but we’ll skip over it, including face texture

indices, or face elements beyond the third. Some of the models I’d like to

test have relative indices, so I want to support those, too. A relative

index refers backwards from the last vertex, so the order of the lines

in an OBJ matter. For example, the cube faces above could have instead

been written:

f -6//-6 -2//-6 -1//-6

f -6//-6 -1//-6 -5//-6

f -8//-5 -4//-5 -3//-5

f -8//-5 -3//-5 -7//-5

f -2//-4 -6//-4 -7//-4

f -2//-4 -7//-4 -3//-4

f -5//-3 -1//-3 -4//-3

f -5//-3 -4//-3 -8//-3

f -1//-2 -2//-2 -3//-2

f -1//-2 -3//-2 -4//-2

f -6//-1 -5//-1 -8//-1

f -6//-1 -8//-1 -7//-1

Due to this the parser cannot be blind to line order, and it must handle

negative indices. Relative indexing has the nice effect that we can group

faces, and those groups are relocatable. We can reorder them without

renumbering the faces, or concatenate models just by concatenating their

OBJ files.

The fundamentals

To start off, we’ll be using an arena of course, trivializing

memory management while swiping aside all hard-coded limits. A quick

reminder of the interface:

#define new(a, n, t) (t *)alloc(a, n, sizeof(t), _Alignof(t))

typedef struct {

char *beg;

char *end;

} Arena;

// Always returns an aligned pointer inside the arena. Allocations are

// zeroed. Does not return on OOM (never returns a null pointer).

void *alloc(Arena *, ptrdiff_t count, ptrdiff_t size, ptrdiff_t align);

Also, no null terminated strings, perhaps the main source of problems with

bespoke parsers.

#define S(s) (Str){s, sizeof(s)-1}

typedef struct {

char *data;

ptrdiff_t len;

} Str;

Pointer arithmetic is error prone, so the tricky stuff is relegated to a

handful of functions, each of which can be exhaustively validated almost

at a glance:

Str span(char *beg, char *end)

{

Str r = {0};

r.data = beg;

r.len = beg ? end-beg : 0;

return r;

}

_Bool equals(Str a, Str b)

{

return a.len==b.len && (!a.len || !memcmp(a.data, b.data, a.len));

}

Str trimleft(Str s)

{

for (; s.len && *s.data<=' '; s.data++, s.len--) {}

return s;

}

Str trimright(Str s)

{

for (; s.len && s.data[s.len-1]<=' '; s.len--) {}

return s;

}

Str substring(Str s, ptrdiff_t i)

{

if (i) {

s.data += i;

s.len -= i;

}

return s;

}

Each avoids the purposeless special cases around null pointers (i.e.

zero-initialized Str objects) that would otherwise work out naturally.

The space character and all control characters are treated as whitespace

for simplicity. When I started writing this parser, I didn’t define all

these functions up front. I defined them as needed. (A good standard

library would have provided similar definitions out-of-the-box.) If

you’re worried about misuse, add the appropriate assertions.

A powerful and useful string function I’ve discovered, and which I use in

every string-heavy program, is cut, a concept I shamelessly stole from

the Go standard library:

typedef struct {

Str head;

Str tail;

_Bool ok;

} Cut;

Cut cut(Str s, char c)

{

Cut r = {0};

if (!s.len) return r; // null pointer special case

char *beg = s.data;

char *end = s.data + s.len;

char *cut = beg;

for (; cut<end && *cut!=c; cut++) {}

r.ok = cut < end;

r.head = span(beg, cut);

r.tail = span(cut+r.ok, end);

return r;

}

It slices, it dices, it juliennes! Need to iterate over lines? Cut it up:

Cut c = {0};

c.tail = input;

while (c.tail.len) {

c = cut(c.tail, '\n');

Str line = c.head;

// ... process line ...

}

Need to iterate over the fields in a line? Cut the line on the field

separator. Then cut the field on the element separator. No allocation, no

mutation (strtok).

Unlike a program designed to process arbitrarily large inputs, the

intention here is to load the entire model into memory. We don’t need to

fiddle around with loading a line of input at at time (fgets, getline,

etc.) — the usual approach with OBJ parsers. If the OBJ source cannot fit

in memory, then the model won’t fit in memory. This greatly simplifies the

parser, not to mention faster while lifting hard-coded limits like maximum

line length.

The simple arena I use makes whole-file loading so easy. Read straight

into the arena without checking the file size (ftell, etc.), which means

streaming inputs (i.e. pipes) work automatically.

Str loadfile(Arena *a, FILE *f)

{

Str r = {0};

r.data = a->beg;

r.len = a->end - a->beg;

r.len = fread(r.data, 1, r.len, f);

return r;

}

Without buffered input, you may need a loop around the read:

Str loadfile(Arena *a, int fd)

{

Str r = {0};

r.data = a.beg;

ptrdiff_t cap = a->end - a->beg;

for (;;) {

ptrdiff_t r = read(fd, r.data+r.len, cap-r.len);

if (r < 1) {

return r; // ignoring read errors

}

r.len += r;

}

}

You might consider triggering an out-of-memory error if the arena was

filled to the brim, which almost certainly means the input was truncated.

Though that’s likely to happen anyway because the next allocation from

that arena will fail.

Side note: When using a multi GB arena, issuing such huge read requests

stress tests the underlying IO system. I’ve found libc bugs this way. In

this case I used SDL2 for the demo, and SDL lost the ability to

read files after I increased the arena size to 4GB in order to test a

gigantic model (“Power Plant”). I’ve run into this before, and

I assumed it was another Microsoft CRT bug. After investigating deeper for

this article, I learned it’s an ancient SDL bug that’s made it all the way

into SDL3. -Wconversion warns about it, but was accidentally squelched

in the 64-bit port back in 2009. It seems nobody else loads files

this way, so watch out for platform bugs if you use this technique!

Parsing data

In practice, rendering systems limit counts to the 32-bit range, which is

reasonable. So in the OBJ parser, vertex and normal indices will be 32-bit

integers. Negatives will be needed for at least relative indexing. Parsing

from a Str means null-terminated functions like strtol are off limits.

So here’s a function to parse a signed integer out of a Str:

int32_t parseint(Str s)

{

uint32_t r = 0;

int32_t sign = 1;

for (ptrdiff_t i = 0; i < s.len; i++) {

switch (s.data[i]) {

case '+': break;

case '-': sign = -1; break;

default : r = 10*r + s.data[i] - '0';

}

}

return r * sign;

}

The uint32_t means its free to overflow. If it overflows, the input was

invalid. If it doesn’t hold an integer, the input was invalid. In either

case it will read a harmless, garbage result. Despite being unsigned, it

works just fine with negative inputs thanks to two’s complement.

For floats I didn’t intend to parse exponential notation, but some models

I wanted to test actually did use it — probably by accident — so I added

it anyway. That requires a function to compute the exponent.

float expt10(int32_t e)

{

float y = 1.0f;

float x = e<0 ? 0.1f : e>0 ? 10.0f : 1.0f;

int32_t n = e<0 ? e : -e;

for (; n < -1; n /= 2) {

y *= n%2 ? x : 1.0f;

x *= x;

}

return x * y;

}

That’s exponentiation by squaring, avoiding signed overflow on the

exponent. Traditionally a negative exponent is inverted, but applying

unary - to an arbitrary integer might overflow (consider -2147483648).

So instead I iterate from the negative end. The negative range is larger

than the positive, after all. Finally we can parse floats:

float parsefloat(Str s)

{

float r = 0.0f;

float sign = 1.0f;

float exp = 0.0f;

for (ptrdiff_t i = 0; i < s.len; i++) {

switch (s.data[i]) {

case '+': break;

case '-': sign = -1; break;

case '.': exp = 1; break;

case 'E':

case 'e': exp = exp ? exp : 1.0f;

exp *= expt10(parseint(substring(s, i+1)));

i = s.len;

break;

default : r = 10.0f*r + (s.data[i] - '0');

exp *= 0.1f;

}

}

return sign * r * (exp ? exp : 1.0f);

}

Probably not as precise as strtof, but good enough for loading a model.

It’s also ~30% faster for this purpose than my system’s strtof. If it

hits an exponent, it combines parseint and expt10 to augment the

result so far. At least for all the models I tried, the exponent only

appeared for tiny values. They round to zero with no visible effects, so

you can cut the implementation by more than half in one fell swoop if you

wish (no more expt10 nor substring either):

switch (s.data[i]) {

// ...

case 'E':

case 'e': return 0; // probably small *shrug*

// ...

}

Why not strtof? That has the rather annoying requirement that input is

null terminated, which is not the case here. Worse, it’s affected by the

locale and doesn’t behave consistently nor reliably.

A vertex is three floats separated by whitespace. So combine cut and

parsefloat to parse one.

typedef struct {

float v[3];

} Vert;

Vert parsevert(Str s)

{

Vert r = {0};

Cut c = cut(trimleft(s), ' ');

r.v[0] = parsefloat(c.head);

c = cut(trimleft(c.tail), ' ');

r.v[1] = parsefloat(c.head);

c = cut(trimleft(c.tail), ' ');

r.v[2] = parsefloat(c.head);

return r;

}

cut parses a field between every space, including empty fields between

adjacent spaces, so trimleft discards extra space before cutting. If the

line ends early, this passes empty strings into parsefloat which come

out as zeros. No special checks required for invalid input.

Faces are a set of three vertex indices and three normal indices, and

parses almost the same way. Relative indices are immediately converted to

absolute indices using the number of vertices/normals so far.

typedef struct {

int32_t v[3];

int32_t n[3];

} Face;

static Face parseface(Str s, ptrdiff_t nverts, ptrdiff_t nnorms)

{

Face r = {0};

Cut fields = {0};

fields.tail = s;

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

fields = cut(trimleft(fields.tail), ' ');

Cut elem = cut(fields.head, '/');

r.v[i] = parseint(elem.head);

elem = cut(elem.tail, '/'); // skip texture

elem = cut(elem.tail, '/');

r.n[i] = parseint(elem.head);

// Process relative subscripts

if (r.v[i] < 0) {

r.v[i] = (int32_t)(r.v[i] + 1 + nverts);

}

if (r.n[i] < 0) {

r.n[i] = (int32_t)(r.n[i] + 1 + nnorms);

}

}

return r;

}

Since nverts must be non-negative, and a relative index is negative by

definition, adding them together can never overflow. If there are too many

vertices, the result might be truncated, as indicated by the cast. That’s

fine. Just invalid input.

There’s an interesting interview question here: Consider this alternative

to the above, maintaining the explicit cast to dismiss the -Wconversion

warning.

r.v[i] += (int32_t)(1 + nverts);

Is it equivalent? Can this overflow? (Answers: No and yes.) If yes, under

what conditions? Unfortunately a fuzz test would never hit it.

Putting it together

For this case, a model is three arrays of vertices, normals, and indices.

While faces only support 32-bit indexing, I use ptrdiff_t in order to

skip overflow checks. There cannot possibly be more vertices than bytes of

source, so these counts cannot overflow.

typedef struct {

Vert *verts;

ptrdiff_t nverts;

Vert *norms;

ptrdiff_t nnorms;

Face *faces;

ptrdiff_t nfaces;

} Model;

Model parseobj(Arena *, Str);

They’d probably look a little nicer as dynamic arrays, but we won’t

need that machinery. That’s because the parser makes two passes over the

OBJ source, the first time to count:

Model m = {0};

Cut lines = {0};

lines.tail = obj;

while (lines.tail.len) {

lines = cut(lines.tail, '\n');

Cut fields = cut(trimright(lines.head), ' ');

Str kind = fields.head;

if (equals(S("v"), kind)) {

m.nverts++;

} else if (equals(S("vn"), kind)) {

m.nnorms++;

} else if (equals(S("f"), kind)) {

m.nfaces++;

}

}

It’s a lightweight pass, skipping over the numeric data. With that

information collected, we can allocate the model:

m.verts = new(a, m.nverts, Vert);

m.norms = new(a, m.nnorms, Vert);

m.faces = new(a, m.nfaces, Face);

m.nverts = m.nnorms = m.nfaces = 0;

On the next pass we call parsevert and parseface to fill it out.

lines.tail = obj;

while (lines.tail.len) {

lines = cut(lines.tail, '\n');

Cut fields = cut(trimright(lines.head), ' ');

Str kind = fields.head;

if (equals(S("v"), kind)) {

m.verts[m.nverts++] = parsevert(fields.tail);

} else if (equals(S("vn"), kind)) {

m.norms[m.nnorms++] = parsevert(fields.tail);

} else if (equals(S("f"), kind)) {

m.faces[m.nfaces++] = parseface(fields.tail, m.nverts, m.nnorms);

}

}

At this point the model is parsed, though its not necessarily consistent.

Faces indices may still be out of range. The next step is to transform it

into a more useful representation.

Rendering the model is the easiest way to verify it came out alright, and

it’s generally useful for debugging problems. Because it basically does

all the hard work for us, and doesn’t require ridiculous contortions to

access, I’m going to render with old school OpenGL 1.1. It provides a

glInterleavedArrays function with a bunch of predefined formats.

The one that interests me is GL_N3F_V3F, where each vertex is a normal

and a position. Each face is three such elements. I came up with this:

typedef struct { // GL_N3F_V3F

Vert n, v;

} N3FV3F[3];

typedef struct {

N3FV3F *data;

ptrdiff_t len;

} N3FV3Fs;

// Transform a model into a GL_N3F_V3F representation.

N3FV3Fs n3fv3fize(Arena *, Model);

If you’re being precise you’d use GLfloat, but this is good enough for

me. By using a different arena for this step, we can discard the OBJ data

once it’s in the “local” format. For example:

Arena perm = {...};

Arena scratch = {...};

N3FV3Fs *scene = new(&perm, nmodels, N3FV3Fs);

for (int i = 0; i < nmodels; i++) {

Arena temp = scratch; // free OBJ at end of iteration

Str obj = loadfile(&temp, path[i]);

Model model = parseobj(&temp, obj);

scene[i] = n3fv3fize(&perm, model);

}

The conversion allocates the GL_N3F_V3F array, discards invalid faces,

and copies the valid faces into the array:

N3FV3Fs n3fv3fize(Arena *a, Model m)

{

N3FV3Fs r = {0};

r.data = new(a, m.nfaces, N3FV3F);

for (ptrdiff_t f = 0; f < m.nfaces; f++) {

_Bool valid = 1;

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

valid &= m.faces[f].v[i]>0 && m.faces[f].v[i]<=m.nverts;

valid &= m.faces[f].n[i]>0 && m.faces[f].n[i]<=m.nnorms;

}

if (valid) {

ptrdiff_t t = r.len++;

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

r.data[t][i].n = m.norms[m.faces[f].n[i]-1];

r.data[t][i].v = m.verts[m.faces[f].v[i]-1];

}

}

}

return r;

}

Here’s what that looks like in OpenGL with suzanne.obj and

bmw.obj:

This was a fun little project, and perhaps you learned a new technique or

two after checking it out.