nullprogram.com/blog/2016/04/30/

For over a decade now, GNU Make has almost exclusively been my build

system of choice, either directly or indirectly. Unfortunately this

means I unnecessarily depend on some GNU extensions — an annoyance when

porting to the BSDs. In an effort to increase the portability of my

Makefiles, I recently read the POSIX make specification. I

learned two important things: 1) POSIX make is so barren it’s not

really worth striving for (update: I’ve changed my mind),

and 2) make’s macro assignment mechanism is Turing-complete.

If you want to see it in action for yourself before reading further,

here’s a Makefile that implements Conway’s Game of Life (40x40) using

only macro assignments.

Run it with any make program in an ANSI terminal. It must literally

be named life.mak. Beware: if you run it longer than a few minutes,

your computer may begin thrashing.

It’s 100% POSIX-compatible except for the sleep 0.1 (fractional

sleep), which is only needed for visual effect.

A POSIX workaround

Unlike virtually every real world implementation, POSIX make doesn’t

support conditional parts. For example, you might want your Makefile’s

behavior to change depending on the value of certain variables. In GNU

Make it looks like this:

ifdef USE_FOO

EXTRA_FLAGS = -ffoo -lfoo

else

EXTRA_FLAGS = -Wbar

endif

Or BSD-style:

.ifdef USE_FOO

EXTRA_FLAGS = -ffoo -lfoo

.else

EXTRA_FLAGS = -Wbar

.endif

If the goal is to write a strictly POSIX Makefile, how could I work

around the lack of conditional parts and maintain a similar interface?

The selection of macro/variable to evaluate can be dynamically

selected, allowing for some useful tricks. First define the option’s

default:

Then define both sets of flags:

EXTRA_FLAGS_0 = -Wbar

EXTRA_FLAGS_1 = -ffoo -lfoo

Now dynamically select one of these macros for assignment to

EXTRA_FLAGS.

EXTRA_FLAGS = $(EXTRA_FLAGS_$(USE_FOO))

The assignment on the command line overrides the assignment in the

Makefile, so the user gets to override USE_FOO.

$ make # EXTRA_FLAGS = -Wbar

$ make USE_FOO=0 # EXTRA_FLAGS = -Wbar

$ make USE_FOO=1 # EXTRA_FLAGS = -ffoo -lfoo

Before reading the POSIX specification, I didn’t realize that the

left side of an assignment can get the same treatment. For example,

if I really want the “if defined” behavior back, I can use the macro

to mangle the left-hand side. For example,

EXTRA_FLAGS = -O0 -g3

EXTRA_FLAGS$(DEBUG) = -O3 -DNDEBUG

Caveat: If DEBUG is set to empty, it may still result in true for

ifdef depending on which make flavor you’re using, but will always

appear to be unset in this hack.

$ make # EXTRA_FLAGS = -O3 -DNDEBUG

$ make DEBUG=yes # EXTRA_FLAGS = -O0 -g3

This last case had me thinking: This is very similar to the (ab)use of

the x86 mov instruction in mov is Turing-complete. These

macro assignments alone should be enough to compute any algorithm.

Macro Operations

Macro names are just keys to a global associative array. This can be

used to build lookup tables. Here’s a Makefile to “compute” the square

root of integers between 0 and 10.

sqrt_0 = 0.000000

sqrt_1 = 1.000000

sqrt_2 = 1.414214

sqrt_3 = 1.732051

sqrt_4 = 2.000000

sqrt_5 = 2.236068

sqrt_6 = 2.449490

sqrt_7 = 2.645751

sqrt_8 = 2.828427

sqrt_9 = 3.000000

sqrt_10 = 3.162278

result := $(sqrt_$(n))

The BSD flavors of make have a -V option for printing variables,

which is an easy way to retrieve output. I used an “immediate”

assignment (:=) for result since some versions of make won’t

evaluate the expression before -V printing.

$ make -f sqrt.mak -V result n=8

2.828427

Without -V, a default target could be used instead:

output :

@printf "$(result)\n"

There are no math operators, so performing arithmetic requires some

creativity. For example, integers could be represented as a

series of x characters. The number 4 is xxxx, the number 6 is

xxxxxx, etc. Addition is concatenation (note: macros can have + in

their names):

A = xxx

B = xxxx

A+B = $(A)$(B)

However, since there’s no way to “slice” a value, subtraction isn’t

possible. A more realistic approach to arithmetic would require lookup

tables.

Branching

Branching could be achieved through more lookup tables. For example,

square_0 = 1

square_1 = 2

square_2 = 4

# ...

result := $($(op)_$(n))

And called as:

$ make n=5 op=sqrt # 2.236068

$ make n=5 op=square # 25

Or using the DEBUG trick above, use the condition to mask out the

results of the unwanted branch. This is similar to the mov paper.

result := $(op)($(n)) = $($(op)_$(n))

result$(verbose) := $($(op)_$(n))

And its usage:

$ make n=5 op=square # 25

$ make n=5 op=square verbose=1 # square(5) = 25

What about loops?

Looping is a tricky problem. However, one of the most common build

(anti?)patterns is the recursive Makefile. Borrowing from the

mov paper, which used an unconditional jump to restart the program

from the beginning, for a Makefile Turing-completeness I can invoke

the Makefile recursively, restarting the program with a new set of

inputs.

Remember the print target above? I can loop by invoking make again

with new inputs in this target,

output :

@printf "$(result)\n"

@$(MAKE) $(args)

Before going any further, now that loops have been added, the natural

next question is halting. In reality, the operating system will take

care of that after some millions of make processes have carelessly

been invoked by this horribly inefficient scheme. However, we can do

better. The program can clobber the MAKE variable when it’s ready to

halt. Let’s formalize it.

loop = $(MAKE) $(args)

output :

@printf "$(result)\n"

@$(loop)

To halt, the program just needs to clear loop.

Suppose we want to count down to 0. There will be an initial count:

A decrement table:

6 = 5

5 = 4

4 = 3

3 = 2

2 = 1

1 = 0

0 = loop

The last line will be used to halt by clearing the name on the right

side. This is three star territory.

The result (current iteration) loop value is computed from the lookup

table.

The next loop value is passed via args. If loop was cleared above,

this result will be discarded.

With all that in place, invoking the Makefile will print a countdown

from 5 to 0 and quit. This is the general structure for the Game of

Life macro program.

Game of Life

A universal Turing machine has been implemented in Conway’s Game of

Life. With all that heavy lifting done, one of the easiest

methods today to prove a language’s Turing-completeness is to

implement Conway’s Game of Life. Ignoring the criminal inefficiency of

it, the Game of Life Turing machine could be run on the Game of Life

simulation running on make’s macro assignments.

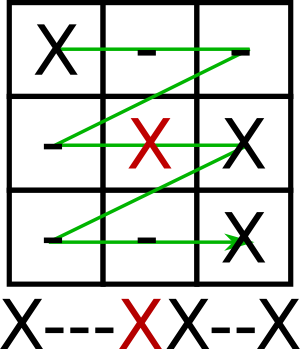

In the Game of Life program — the one linked at the top of this

article — each cell is stored in a macro named xxyy, after its

position. The top-left most cell is named 0000, then going left to

right, 0100, 0200, etc. Providing input is a matter of assigning each

of these macros. I chose X for alive and - for dead, but, as

you’ll see, any two characters permitted in macro names would work as

well.

$ make 0000=X 0100=- 0200=- 0300=X ...

The next part should be no surprise: The rules of the Game of Life are

encoded as a 512-entry lookup table. The key is formed by

concatenating the cell’s value along with all its neighbors, with

itself in the center.

The “beginning” of the table looks like this:

--------- = -

X-------- = -

-X------- = -

XX------- = -

--X------ = -

X-X------ = -

-XX------ = -

XXX------ = X

---X----- = -

X--X----- = -

-X-X----- = -

XX-X----- = X

# ...

Note: The two right-hand X values here are the cell coming to life

(exactly three living neighbors). Computing the next value (n0101)

for 0101 is done like so:

n0101 = $($(0000)$(0100)$(0200)$(0001)$(0101)$(0201)$(0002)$(0102)$(0202))

Given these results, constructing the input to the next loop is

simple:

args = 0000=$(n0000) 0100=$(n0100) 0200=$(n0200) ...

The display output, to be given to printf, is built similarly:

output = $(n0000)$(n0100)$(n0200)$(n0300)...

In the real version, this is decorated with an ANSI escape code that

clears the terminal. The printf interprets the escape byte (\033)

so that it doesn’t need to appear literally in the source.

And that’s all there is to it: Conway’s Game of Life running in a

Makefile. Life, uh, finds a way.