nullprogram.com/blog/2017/04/27/

Update 2020: A DOS build of Connect Four was featured on GET OFF MY

LAWN.

Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS) is the most impressive game

artificial intelligence I’ve ever used. At its core it simulates a

large number of games (playouts), starting from the current game

state, using random moves for each player. Then it simply picks the

move where it won most often. This description is sufficient to spot

one of its most valuable features: MCTS requires no knowledge of

strategy or effective play. The game’s rules — enough to simulate

the game — are all that’s needed to allow the AI to make decent moves.

Expert knowledge still makes for a stronger AI, but, more many games,

it’s unnecessary to construct a decent opponent.

A second valuable feature is that it’s easy to parallelize. Unlike

alpha-beta pruning, which doesn’t mix well with parallel

searches of a Minimax tree, Monte Carlo simulations are practically

independent and can be run in parallel.

Finally, the third valuable feature is that the search can be stopped

at any time. The completion of any single simulation is as good a

stopping point as any. It could be due to a time limit, a memory

limit, or both. In general, the algorithm converges to a best move

rather than suddenly discovering it. The good moves are identified

quickly, and further simulations work to choose among them. More

simulations make for better moves, with exponentially diminishing

returns. Contrasted with Minimax, stopping early has the risk that the

good moves were never explored at all.

To try out MCTS myself, I wrote two games employing it:

They’re both written in C, for both unix-like and Windows, and should

be easy to build. I challenge you to beat them both. The

Yavalath AI is easier to beat due to having blind spots, which I’ll

discuss below. The Connect Four AI is more difficult and will likely

take a number of tries.

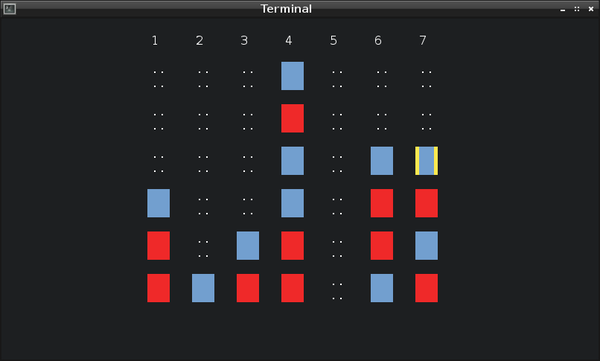

Connect Four

MCTS works very well with Connect Four, and only requires modest

resources: 32MB of memory to store the results of random playouts, and

500,000 game simulations. With a few tweaks, it can even be run in

DOSBox. It stops when it hits either of those limits. In theory,

increasing both would make for stronger moves, but in practice I can’t

detect any difference. It’s like computing pi with Monte Carlo,

where eventually it just runs out of precision to make any more

progress.

Based on my simplified description above, you might wonder why it needs

all that memory. Not only does MCTS need to track its win/loss ratio for

each available move from the current state, it tracks the win/loss ratio

for moves in the states behind those moves. A large chunk of the game

tree is kept in memory to track all of the playout results. This is why

MCTS needs a lot more memory than Minimax, which can discard branches

that have been searched.

A convenient property of this tree is that the branch taken in the

actual game can be re-used in a future search. The root of the tree

becomes the node representing the taken game state, which has already

seen a number of playouts. Even better, MCTS is weighted towards

exploring good moves over bad moves, and good moves are more likely to

be taken in the real game. In general, a significant portion of the tree

gets to be reused in a future search.

I’m going to skip most of the details of the algorithm itself and focus

on my implementation. Other articles do a better job at detailing the

algorithm than I could.

My Connect Four engine doesn’t use dynamic allocation for this tree (or

at all). Instead it manages a static buffer — an array of tree nodes,

each representing a game state. All nodes are initially chained together

into a linked list of free nodes. As the tree is built, nodes are pulled

off the free list and linked together into a tree. When the game

advances to the next state, nodes on unreachable branches are added back

to the free list.

If at any point the free list is empty when a new node is needed, the

current search aborts. This is the out-of-memory condition, and no more

searching can be performed.

/* Connect Four is normally a 7 by 6 grid. */

#define CONNECT4_WIDTH 7

#define CONNECT4_HEIGHT 6

struct connect4_node {

uint32_t next[CONNECT4_WIDTH]; // "pointer" to next node

uint32_t playouts[CONNECT4_WIDTH]; // number of playouts

float score[CONNECT4_WIDTH]; // pseudo win/loss ratio

};

Rather than native C pointers, the structure uses 32-bit indexes into

the master array. This saves a lot of memory on 64-bit systems, and the

structure is the same size no matter the pointer size of the host. The

next field points to the next state for the nth move. Since 0 is a

valid index, -1 represents null (CONNECT4_NULL).

Each column is a potential move, so there are CONNECT4_WIDTH

possible moves at any given state. Each move has a floating point

score and a total number of playouts through that move. In my

implementation, the search can also halt due to an overflow in a

playout counter. The search can no longer be tracked in this

representation, so it has to stop. This generally only happens when

the game is nearly over and it’s grinding away on a small number of

possibilities.

Note that the actual game state (piece positions) is not tracked in the

node structure. That’s because it’s implicit. We know the state of the

game at the root, and simulating the moves while descending the tree

will keep track of the board state at the current node. That’s more

memory savings.

The state itself is a pair of bitboards, one for each player. Each

position on the grid gets a bit on each bitboard. The bitboard is very

fast to manipulate, and win states are checked with just a handful of

bit operations. My intention was to make playouts as fast as possible.

struct connect4_ai {

uint64_t state[2]; // game state at root (bitboard)

uint64_t rng[2]; // random number generator state

uint32_t nodes_available; // total number of nodes available

uint32_t nodes_allocated; // number of nodes in the tree

uint32_t root; // "pointer" to root node

uint32_t free; // "pointer" to free list

int turn; // whose turn (0 or 1) at the root?

};

The nodes_available and nodes_allocated are not necessary for

correctness nor speed. They’re useful for diagnostics and debugging.

All the functions that operate on these two structures are

straightforward, except for connect4_playout, a recursive function

which implements the bulk of MCTS. Depending on the state of the node

it’s at, it does one of two things:

-

If there are unexplored moves (playouts == 0), it randomly chooses

an unplayed move, allocates exactly one node for the state behind that

move, and simulates the rest of the game in a loop, without recursion

or allocating any more nodes.

-

If all moves have been explored at least once, it uses an upper

confidence bound (UCB1) to randomly choose a move, weighed towards

both moves that are under-explored and moves which are strongest.

Striking that balance is one of the challenges. It recurses into that

next state, then updates the node with the result as it propagates

back to the root.

That’s pretty much all there is to it.

Yavalath

Yavalath is a board game invented by a computer

program. It’s a pretty fascinating story. The depth and strategy

are disproportionately deep relative to its dead simple rules: Get four

in a row without first getting three in a row. The game revolves around

forced moves.

The engine is structured almost identically to the Connect Four engine.

It uses 32-bit indexes instead of pointers. The game state is a pair of

bitboards, with end-game masks computed at compile time via

metaprogramming. The AI allocates the tree from a single, massive

buffer — multiple GBs in this case, dynamically scaled to the available

physical memory. And the core MCTS function is nearly identical.

One important difference is that identical game states — states where

the pieces on the board are the same, but the node was reached through

a different series of moves — are coalesced into a single state in the

tree. This state deduplication is done through a hash table. This

saves on memory and allows multiple different paths through the game

tree to share playouts. It comes at a cost of including the game state

in the node (so it can be identified in the hash table) and reference

counting the nodes (since they might have more than one parent).

Unfortunately the AI has blind spots, and once you learn to spot them it

becomes easy to beat consistently. It can’t spot certain kinds of forced

moves, so it always falls for the same tricks. The official Yavalath

AI is slightly stronger than mine, but has a similar blindness. I think

MCTS just isn’t quite a good fit for Yavalath.

The AI’s blindness is caused by shallow traps, a common problem

for MCTS. It’s what makes MCTS a poor fit for Chess. A shallow trap is

a branch in the game tree where the game will abruptly end in a small

number of turns. If the random tree search doesn’t luckily stumble

upon a trap during its random traversal, it can’t take it into account

in its final decision. A skilled player will lead the game towards one

of these traps, and the AI will blunder along, not realizing what’s

happened until its too late.

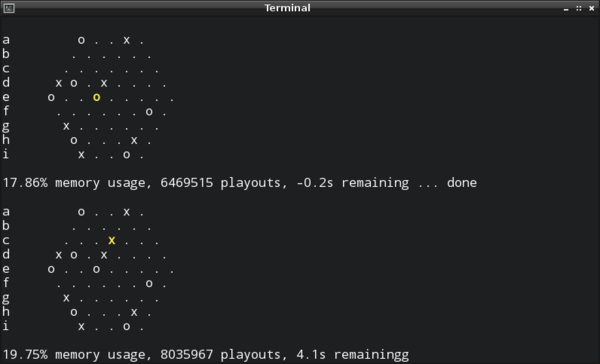

I almost feel bad for it when this happens. If you watch the memory

usage and number of playouts, once it falls into a trap, you’ll see it

using almost no memory while performing a ton of playouts. It’s

desperately, frantically searching for a way out of the trap. But it’s

too late, little AI.

I’m really happy to have sunk a couple weekends into playing with MCTS.

It’s not always a great fit, as seen with Yavalath, but it’s a really

neat algorithm. Now that I’ve wrapped my head around it, I’ll be ready

to use it should I run into an appropriate problem in the future.