nullprogram.com/blog/2017/11/03/

Update 2020: I’ve produced many more examples over the years

(even more).

In a previous article I demonstrated video filtering with C and a

unix pipeline. Thanks to the ubiquitous support for the

ridiculously simple Netpbm formats — specifically the “Portable

PixMap” (.ppm, P6) binary format — it’s trivial to parse and

produce image data in any language without image libraries. Video

decoders and encoders at the ends of the pipeline do the heavy lifting

of processing the complicated video formats actually used to store and

transmit video.

Naturally this same technique can be used to produce new video in a

simple program. All that’s needed are a few functions to render

artifacts — lines, shapes, etc. — to an RGB buffer. With a bit of

basic sound synthesis, the same concept can be applied to create audio

in a separate audio stream — in this case using the simple (but not as

simple as Netpbm) WAV format. Put them together and a small,

standalone program can create multimedia.

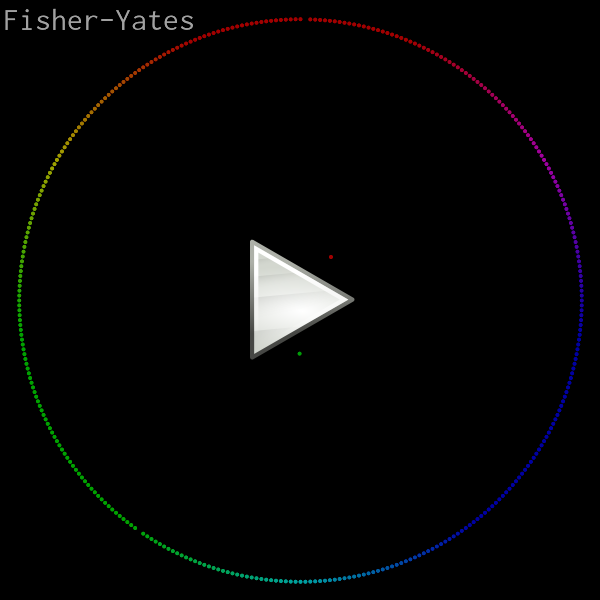

Here’s the demonstration video I’ll be going through in this article.

It animates and visualizes various in-place sorting algorithms (see

also). The elements are rendered as colored dots, ordered by

hue, with red at 12 o’clock. A dot’s distance from the center is

proportional to its corresponding element’s distance from its correct

position. Each dot emits a sinusoidal tone with a unique frequency

when it swaps places in a particular frame.

Original credit for this visualization concept goes to w0rthy.

All of the source code (less than 600 lines of C), ready to run, can be

found here:

On any modern computer, rendering is real-time, even at 60 FPS, so you

may be able to pipe the program’s output directly into your media player

of choice. (If not, consider getting a better media player!)

$ ./sort | mpv --no-correct-pts --fps=60 -

VLC requires some help from ppmtoy4m:

$ ./sort | ppmtoy4m -F60:1 | vlc -

Or you can just encode it to another format. Recent versions of

libavformat can input PPM images directly, which means x264 can read

the program’s output directly:

$ ./sort | x264 --fps 60 -o video.mp4 /dev/stdin

By default there is no audio output. I wish there was a nice way to

embed audio with the video stream, but this requires a container and

that would destroy all the simplicity of this project. So instead, the

-a option captures the audio in a separate file. Use ffmpeg to

combine the audio and video into a single media file:

$ ./sort -a audio.wav | x264 --fps 60 -o video.mp4 /dev/stdin

$ ffmpeg -i video.mp4 -i audio.wav -vcodec copy -acodec mp3 \

combined.mp4

You might think you’ll be clever by using mkfifo (i.e. a named pipe)

to pipe both audio and video into ffmpeg at the same time. This will

only result in a deadlock since neither program is prepared for this.

One will be blocked writing one stream while the other is blocked

reading on the other stream.

Several years ago my intern and I used the exact same pure C

rendering technique to produce these raytracer videos:

I also used this technique to illustrate gap buffers.

This program really only has one purpose: rendering a sorting video

with a fixed, square resolution. So rather than write generic image

rendering functions, some assumptions will be hard coded. For example,

the video size will just be hard coded and assumed square, making it

simpler and faster. I chose 800x800 as the default:

Rather than define some sort of color struct with red, green, and blue

fields, color will be represented by a 24-bit integer (long). I

arbitrarily chose red to be the most significant 8 bits. This has

nothing to do with the order of the individual channels in Netpbm

since these integers are never dumped out. (This would have stupid

byte-order issues anyway.) “Color literals” are particularly

convenient and familiar in this format. For example, the constant for

pink: 0xff7f7fUL.

In practice the color channels will be operated upon separately, so

here are a couple of helper functions to convert the channels between

this format and normalized floats (0.0–1.0).

static void

rgb_split(unsigned long c, float *r, float *g, float *b)

{

*r = ((c >> 16) / 255.0f);

*g = (((c >> 8) & 0xff) / 255.0f);

*b = ((c & 0xff) / 255.0f);

}

static unsigned long

rgb_join(float r, float g, float b)

{

unsigned long ir = roundf(r * 255.0f);

unsigned long ig = roundf(g * 255.0f);

unsigned long ib = roundf(b * 255.0f);

return (ir << 16) | (ig << 8) | ib;

}

Originally I decided the integer form would be sRGB, and these

functions handled the conversion to and from sRGB. Since it had no

noticeable effect on the output video, I discarded it. In more

sophisticated rendering you may want to take this into account.

The RGB buffer where images are rendered is just a plain old byte

buffer with the same pixel format as PPM. The ppm_set() function

writes a color to a particular pixel in the buffer, assumed to be S

by S pixels. The complement to this function is ppm_get(), which

will be needed for blending.

static void

ppm_set(unsigned char *buf, int x, int y, unsigned long color)

{

buf[y * S * 3 + x * 3 + 0] = color >> 16;

buf[y * S * 3 + x * 3 + 1] = color >> 8;

buf[y * S * 3 + x * 3 + 2] = color >> 0;

}

static unsigned long

ppm_get(unsigned char *buf, int x, int y)

{

unsigned long r = buf[y * S * 3 + x * 3 + 0];

unsigned long g = buf[y * S * 3 + x * 3 + 1];

unsigned long b = buf[y * S * 3 + x * 3 + 2];

return (r << 16) | (g << 8) | b;

}

Since the buffer is already in the right format, writing an image is

dead simple. I like to flush after each frame so that observers

generally see clean, complete frames. It helps in debugging.

static void

ppm_write(const unsigned char *buf, FILE *f)

{

fprintf(f, "P6\n%d %d\n255\n", S, S);

fwrite(buf, S * 3, S, f);

fflush(f);

}

Dot rendering

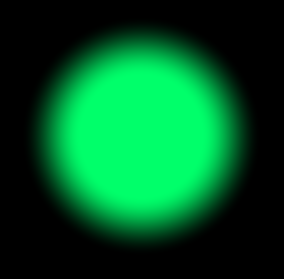

If you zoom into one of those dots, you may notice it has a nice

smooth edge. Here’s one rendered at 30x the normal resolution. I did

not render, then scale this image in another piece of software. This

is straight out of the C program.

In an early version of this program I used a dumb dot rendering

routine. It took a color and a hard, integer pixel coordinate. All the

pixels within a certain distance of this coordinate were set to the

color, everything else was left alone. This had two bad effects:

-

Dots jittered as they moved around since their positions were

rounded to the nearest pixel for rendering. A dot would be centered on

one pixel, then suddenly centered on another pixel. This looked bad

even when those pixels were adjacent.

-

There’s no blending between dots when they overlap, making the lack of

anti-aliasing even more pronounced.

Instead the dot’s position is computed in floating point and is

actually rendered as if it were between pixels. This is done with a

shader-like routine that uses smoothstep — just as found in

shader languages — to give the dot a smooth edge. That edge

is blended into the image, whether that’s the background or a

previously-rendered dot. The input to the smoothstep is the distance

from the floating point coordinate to the center (or corner?) of the

pixel being rendered, maintaining that between-pixel smoothness.

Rather than dump the whole function here, let’s look at it piece by

piece. I have two new constants to define the inner dot radius and the

outer dot radius. It’s smooth between these radii.

#define R0 (S / 400.0f) // dot inner radius

#define R1 (S / 200.0f) // dot outer radius

The dot-drawing function takes the image buffer, the dot’s coordinates,

and its foreground color.

static void

ppm_dot(unsigned char *buf, float x, float y, unsigned long fgc);

The first thing to do is extract the color components.

float fr, fg, fb;

rgb_split(fgc, &fr, &fg, &fb);

Next determine the range of pixels over which the dot will be draw.

These are based on the two radii and will be used for looping.

int miny = floorf(y - R1 - 1);

int maxy = ceilf(y + R1 + 1);

int minx = floorf(x - R1 - 1);

int maxx = ceilf(x + R1 + 1);

Here’s the loop structure. Everything else will be inside the innermost

loop. The dx and dy are the floating point distances from the center

of the dot.

for (int py = miny; py <= maxy; py++) {

float dy = py - y;

for (int px = minx; px <= maxx; px++) {

float dx = px - x;

/* ... */

}

}

Use the x and y distances to compute the distance and smoothstep

value, which will be the alpha. Within the inner radius the color is

on 100%. Outside the outer radius it’s 0%. Elsewhere it’s something in

between.

float d = sqrtf(dy * dy + dx * dx);

float a = smoothstep(R1, R0, d);

Get the background color, extract its components, and blend the

foreground and background according to the computed alpha value. Finally

write the pixel back into the buffer.

unsigned long bgc = ppm_get(buf, px, py);

float br, bg, bb;

rgb_split(bgc, &br, &bg, &bb);

float r = a * fr + (1 - a) * br;

float g = a * fg + (1 - a) * bg;

float b = a * fb + (1 - a) * bb;

ppm_set(buf, px, py, rgb_join(r, g, b));

That’s all it takes to render a smooth dot anywhere in the image.

Rendering the array

The array being sorted is just a global variable. This simplifies some

of the sorting functions since a few are implemented recursively. They

can call for a frame to be rendered without needing to pass the full

array. With the dot-drawing routine done, rendering a frame is easy:

#define N 360 // number of dots

static int array[N];

static void

frame(void)

{

static unsigned char buf[S * S * 3];

memset(buf, 0, sizeof(buf));

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

float delta = abs(i - array[i]) / (N / 2.0f);

float x = -sinf(i * 2.0f * PI / N);

float y = -cosf(i * 2.0f * PI / N);

float r = S * 15.0f / 32.0f * (1.0f - delta);

float px = r * x + S / 2.0f;

float py = r * y + S / 2.0f;

ppm_dot(buf, px, py, hue(array[i]));

}

ppm_write(buf, stdout);

}

The buffer is static since it will be rather large, especially if S

is cranked up. Otherwise it’s likely to overflow the stack. The

memset() fills it with black. If you wanted a different background

color, here’s where you change it.

For each element, compute its delta from the proper array position,

which becomes its distance from the center of the image. The angle is

based on its actual position. The hue() function (not shown in this

article) returns the color for the given element.

With the frame() function complete, all I need is a sorting function

that calls frame() at appropriate times. Here are a couple of

examples:

static void

shuffle(int array[N], uint64_t *rng)

{

for (int i = N - 1; i > 0; i--) {

uint32_t r = pcg32(rng) % (i + 1);

swap(array, i, r);

frame();

}

}

static void

sort_bubble(int array[N])

{

int c;

do {

c = 0;

for (int i = 1; i < N; i++) {

if (array[i - 1] > array[i]) {

swap(array, i - 1, i);

c = 1;

}

}

frame();

} while (c);

}

Synthesizing audio

To add audio I need to keep track of which elements were swapped in

this frame. When producing a frame I need to generate and mix tones

for each element that was swapped.

Notice the swap() function above? That’s not just for convenience.

That’s also how things are tracked for the audio.

static int swaps[N];

static void

swap(int a[N], int i, int j)

{

int tmp = a[i];

a[i] = a[j];

a[j] = tmp;

swaps[(a - array) + i]++;

swaps[(a - array) + j]++;

}

Before we get ahead of ourselves I need to write a WAV header.

Without getting into the purpose of each field, just note that the

header has 13 fields, followed immediately by 16-bit little endian PCM

samples. There will be only one channel (monotone).

#define HZ 44100 // audio sample rate

static void

wav_init(FILE *f)

{

emit_u32be(0x52494646UL, f); // "RIFF"

emit_u32le(0xffffffffUL, f); // file length

emit_u32be(0x57415645UL, f); // "WAVE"

emit_u32be(0x666d7420UL, f); // "fmt "

emit_u32le(16, f); // struct size

emit_u16le(1, f); // PCM

emit_u16le(1, f); // mono

emit_u32le(HZ, f); // sample rate (i.e. 44.1 kHz)

emit_u32le(HZ * 2, f); // byte rate

emit_u16le(2, f); // block size

emit_u16le(16, f); // bits per sample

emit_u32be(0x64617461UL, f); // "data"

emit_u32le(0xffffffffUL, f); // byte length

}

Rather than tackle the annoying problem of figuring out the total

length of the audio ahead of time, I just wave my hands and write the

maximum possible number of bytes (0xffffffff). Most software that

can read WAV files will understand this to mean the entire rest of the

file contains samples.

With the header out of the way all I have to do is write 1/60th of a

second worth of samples to this file each time a frame is produced.

That’s 735 samples (1,470 bytes) at 44.1kHz.

The simplest place to do audio synthesis is in frame() right after

rendering the image.

#define FPS 60 // output framerate

#define MINHZ 20 // lowest tone

#define MAXHZ 1000 // highest tone

static void

frame(void)

{

/* ... rendering ... */

/* ... synthesis ... */

}

With the largest tone frequency at 1kHz, Nyquist says we only

need to sample at 2kHz. 8kHz is a very common sample rate and gives

some overhead space, making it a good choice. However, I found that

audio encoding software was a lot happier to accept the standard CD

sample rate of 44.1kHz, so I stuck with that.

The first thing to do is to allocate and zero a buffer for this

frame’s samples.

int nsamples = HZ / FPS;

static float samples[HZ / FPS];

memset(samples, 0, sizeof(samples));

Next determine how many “voices” there are in this frame. This is used

to mix the samples by averaging them. If an element was swapped more

than once this frame, it’s a little louder than the others — i.e. it’s

played twice at the same time, in phase.

int voices = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

voices += swaps[i];

Here’s the most complicated part. I use sinf() to produce the

sinusoidal wave based on the element’s frequency. I also use a parabola

as an envelope to shape the beginning and ending of this tone so that

it fades in and fades out. Otherwise you get the nasty, high-frequency

“pop” sound as the wave is given a hard cut off.

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

if (swaps[i]) {

float hz = i * (MAXHZ - MINHZ) / (float)N + MINHZ;

for (int j = 0; j < nsamples; j++) {

float u = 1.0f - j / (float)(nsamples - 1);

float parabola = 1.0f - (u * 2 - 1) * (u * 2 - 1);

float envelope = parabola * parabola * parabola;

float v = sinf(j * 2.0f * PI / HZ * hz) * envelope;

samples[j] += swaps[i] * v / voices;

}

}

}

Finally I write out each sample as a signed 16-bit value. I flush the

frame audio just like I flushed the frame image, keeping them somewhat

in sync from an outsider’s perspective.

for (int i = 0; i < nsamples; i++) {

int s = samples[i] * 0x7fff;

emit_u16le(s, wav);

}

fflush(wav);

Before returning, reset the swap counter for the next frame.

memset(swaps, 0, sizeof(swaps));

Font rendering

You may have noticed there was text rendered in the corner of the video

announcing the sort function. There’s font bitmap data in font.h which

gets sampled to render that text. It’s not terribly complicated, but

you’ll have to study the code on your own to see how that works.

Learning more

This simple video rendering technique has served me well for some

years now. All it takes is a bit of knowledge about rendering. I

learned quite a bit just from watching Handmade Hero, where

Casey writes a software renderer from scratch, then implements a

nearly identical renderer with OpenGL. The more I learn about

rendering, the better this technique works.

Before writing this post I spent some time experimenting with using a

media player as a interface to a game. For example, rather than render

the game using OpenGL or similar, render it as PPM frames and send it

to the media player to be displayed, just as game consoles drive

television sets. Unfortunately the latency is horrible — multiple

seconds — so that idea just doesn’t work. So while this technique is

fast enough for real time rendering, it’s no good for interaction.