nullprogram.com/blog/2020/10/19/

Update: I solved another game using essentially the same

technique.

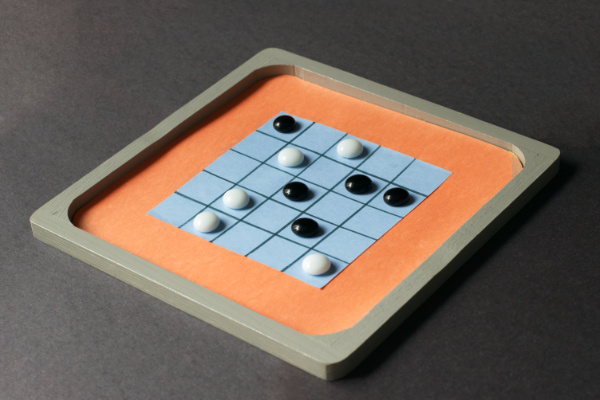

British Square is a 1978 abstract strategy board game which I

recently discovered from a YouTube video. It’s well-suited to play

by pencil-and-paper, so my wife and I played a few rounds to try it out.

Curious about strategies, I searched online for analysis and found

nothing whatsoever, meaning I’d have to discover strategies for myself.

This is exactly the sort of problem that nerd snipes, and so I

sunk a couple of evenings building an analysis engine in C — enough to

fully solve the game and play perfectly.

Repository: British Square Analysis Engine

(and prebuilt binaries)

The game is played on a 5-by-5 grid with two players taking turns

placing pieces of their color. Pieces may not be placed on tiles

4-adjacent to an opposing piece, and as a special rule, the first player

may not play the center tile on the first turn. Players pass when they

have no legal moves, and the game ends when both players pass. The score

is the difference between the piece counts for each player.

In the default configuration, my engine takes a few seconds to explore

the full game tree, then presents the minimax values for the

current game state along with the list of perfect moves. The UI allows

manually exploring down the game tree. It’s intended for analysis, but

there’s enough UI present to “play” against the AI should you so wish.

For some of my analysis I made small modifications to the program to

print or count game states matching certain conditions.

Game analysis

Not accounting for symmetries, there are 4,233,789,642,926,592 possible

playouts. In these playouts, the first player wins 2,179,847,574,830,592

(~51%), the second player wins 1,174,071,341,606,400 (~28%), and the

remaining 879,870,726,489,600 (~21%) are ties. It’s immediately obvious

the first player has a huge advantage.

Accounting for symmetries, there are 8,659,987 total game states. Of

these, 6,955 are terminal states, of which the first player wins 3,599

(~52%) and the second player wins 2,506 (~36%). This small number of

states is what allows the engine to fully explore the game tree in a few

seconds.

Most importantly: The first player can always win by two points. In

other words, it’s not like Tic-Tac-Toe where perfect play by both

players results in a tie. Due to the two-point margin, the first player

also has more room for mistakes and usually wins even without perfect

play. There are fewer opportunities to blunder, and a single blunder

usually results in a lower win score. The second player has a narrow

lane of perfect play, making it easy to blunder.

Below is the minimax analysis for the first player’s options. The number

is the first player’s score given perfect play from that point — i.e.

perfect play starts on the tiles marked “2”, and the tiles marked “0”

are blunders that lead to ties.

11111

12021

10-01

12021

11111

The special center rule probably exists to reduce the first player’s

obvious advantage, but in practice it makes little difference. Without

the rule, the first player has an additional (fifth) branch for a win by

two points:

11111

12021

10201

12021

11111

Improved alternative special rule: Bias the score by two in favor of

the second player. This fully eliminates the first player’s advantage,

perfect play by both sides results in a tie, and both players have a

narrow lane of perfect play.

The four tie openers are interesting because the reasoning does not

require computer assistance. If the first player opens on any of those

tiles, the second player can mirror each of the first player’s moves,

guaranteeing a tie. Note: The first player can still make mistakes that

results in a second player win if the second player knows when to stop

mirroring.

One of my goals was to develop a heuristic so that even human players

can play perfectly from memory, as in Tic-Tac-Toe. Unfortunately I was

not able to develop any such heuristic, though I was able to prove

that a greedy heuristic — always claim as much territory as possible —

is often incorrect and, in some cases, leads to blunders.

Engine implementation

As I’ve done before, my engine represents the game using

bitboards. Each player has a 25-bit bitboard representing their

pieces. To make move validation more efficient, it also sometimes tracks

a “mask” bitboard where invalid moves have been masked. Updating all

bitboards is cheap (place(), mask()), as is validating moves

against the mask (valid()).

The longest possible game is 32 moves. This would just fit in 5 bits,

except that I needed a special “invalid” turn, making it a total of 33

bits. So I use 6 bits to store the turn counter.

Besides generally being unnecessary, the validation masks can be derived

from the main bitboards, so I don’t need to store them in the game tree.

That means I need 25 bits per player, and 6 bits for the counter: 56

bits total. I pack these into a 64-bit integer. The first player’s

bitboard goes in the bottom 25 bits, the second player in the next 25

bits, and the turn counter in the topmost 6 bits. The turn counter

starts at 1, so an all zero state is invalid. I exploit this in the hash

table so that zeroed slots are empty (more on this later).

In other words, the empty state is 0x4000000000000 (INIT) and zero

is the null (invalid) state.

Since the state is so small, rather than passing a pointer to a state to

be acted upon, bitboard functions return a new bitboard with the

requested changes… functional style.

// Compute bitboard+mask where first play is tile 6

// -----

// -X---

// -----

// -----

// -----

uint64_t b = INIT;

uint64_t m = INIT;

b = place(b, 6);

m = mask(m, 6);

Minimax costs

The engine uses minimax to propagate information up the tree. Since the

search extends to the very bottom of the tree, the minimax “heuristic”

evaluation function is the actual score, not an approximation, which is

why it’s able to play perfectly.

When I’ve used minimax before, I built an actual tree data

structure in memory, linking states by pointer / reference. In this

engine there is no such linkage, and instead the links are computed

dynamically via the validation masks. Storing the pointers is more

expensive than computing their equivalents on the fly, so I don’t store

them. Therefore my game tree only requires 56 bits per node — or 64

bits in practice since I’m using a 64-bit integer. With only 8,659,987

nodes to store, that’s a mere 66MiB of memory! This analysis could have

easily been done on commodity hardware two decades ago.

What about the minimax values? Game scores range from -10 to 11: 22

distinct values. (That the first player can score up to 11 and the

second player at most 10 is another advantage to going first.) That’s 5

bits of information. However, I didn’t have this information up front,

and so I assumed a range from -25 to 25, which requires 6 bits.

There are still 8 spare bits left in the 64-bit integer, so I use 6 of

them for the minimax score. Rather than worry about two’s complement, I

bias the score to eliminate negative values before storing it. So the

minimax score rides along for free above the state bits.

Hash table (memoization)

The vast majority of game tree branches are redundant. Even without

taking symmetries into account, nearly all states are reachable from

multiple branches. Exploring all these redundant branches would take

centuries. If I run into a state I’ve seen before, I don’t want to

recompute it.

Once I’ve computed a result, I store it in a hash table so that I can

find it later. Since the state is just a 64-bit integer, I use an

integer hash function to compute a starting index from which to

linearly probe an open addressing hash table. The entire hash table

implementation is literally a dozen lines of code:

uint64_t *

lookup(uint64_t bitboard)

{

static uint64_t table[N];

uint64_t mask = 0xffffffffffffff; // sans minimax

uint64_t hash = bitboard;

hash *= 0xcca1cee435c5048f;

hash ^= hash >> 32;

for (size_t i = hash % N; ; i = (i + 1) % N) {

if (!table[i] || table[i]&mask == bitboard) {

return &table[i];

}

}

}

If the bitboard is not found, it returns a pointer to the (zero-valued)

slot where it should go so that the caller can fill it in.

Canonicalization

Memoization eliminates nearly all redundancy, but there’s still a major

optimization left. Many states are equivalent by symmetry or reflection.

Taking that into account, about 7/8th of the remaining work can still be

eliminated.

Multiple different states that are identical by symmetry must to be

somehow “folded” into a single, canonical state to represent them all.

I do this by visiting all 8 rotations and reflections and choosing the

one with the smallest 64-bit integer representation.

I only need two operations to visit all 8 symmetries, and I chose

transpose (flip around the diagonal) and vertical flip. Alternating

between these operations visits each symmetry. Since they’re bitboards,

transforms can be implemented using fancy bit-twiddling hacks.

Chess boards, with their power-of-two dimensions, have useful properties

which these British Square boards lack, so this is the best I could come

up with:

// Transpose a board or mask (flip along the diagonal).

uint64_t

transpose(uint64_t b)

{

return ((b >> 16) & 0x00000020000010) |

((b >> 12) & 0x00000410000208) |

((b >> 8) & 0x00008208004104) |

((b >> 4) & 0x00104104082082) |

((b >> 0) & 0xfe082083041041) |

((b << 4) & 0x01041040820820) |

((b << 8) & 0x00820800410400) |

((b << 12) & 0x00410000208000) |

((b << 16) & 0x00200000100000);

}

// Flip a board or mask vertically.

uint64_t

flipv(uint64_t b)

{

return ((b >> 20) & 0x0000003e00001f) |

((b >> 10) & 0x000007c00003e0) |

((b >> 0) & 0xfc00f800007c00) |

((b << 10) & 0x001f00000f8000) |

((b << 20) & 0x03e00001f00000);

}

These transform both players’ bitboards in parallel while leaving the

turn counter intact. The logic here is quite simple: Shift the bitboard

a little bit at a time while using a mask to deposit bits in their new

home once they’re lined up. It’s like a coin sorter. Vertical flip is

analogous to byte-swapping, though with 5-bit “bytes”.

Canonicalizing a bitboard now looks like this:

uint64_t

canonicalize(uint64_t b)

{

uint64_t c = b;

b = transpose(b); c = c < b ? c : b;

b = flipv(b); c = c < b ? c : b;

b = transpose(b); c = c < b ? c : b;

b = flipv(b); c = c < b ? c : b;

b = transpose(b); c = c < b ? c : b;

b = flipv(b); c = c < b ? c : b;

b = transpose(b); c = c < b ? c : b;

return c;

}

Callers need only use canonicalize() on values they pass to lookup()

or store in the table (via the returned pointer).

Developing a heuristic

If you can come up with a perfect play heuristic, especially one that

can be reasonably performed by humans, I’d like to hear it. My engine

has a built-in heuristic tester, so I can test it against perfect play

at all possible game positions to check that it actually works. It’s

currently programmed to test the greedy heuristic and print out the

millions of cases where it fails. Even a heuristic that fails in only a

small number of cases would be pretty reasonable.