nullprogram.com/blog/2022/05/22/

This article was discussed on Lobsters.

Earlier this month Ted Unangst researched compiling the OpenBSD kernel

50% faster, which involved stubbing out the largest, extraneous

branches of the source tree. To find the lowest-hanging fruit, he wrote a

tool called watc — where’s all the code — that displays an

interactive “usage” summary of a source tree oriented around line count. A

followup post about exploring the tree in parallel got me thinking

about the problem, especially since I had just written about a concurrent

queue. Turning it over in my mind, I saw opportunities for interesting

data structures and memory management, and so I wanted to write my own

version of the tool, watc.c, which is the subject of this

article.

The original watc is interactive and written in idiomatic Go. My version

is non-interactive, written in C, and currently only supports Windows. Not

only do I prefer batch programs generally, building an interactive user

interface would be complicated and distract from the actual problem I

wanted to tackle. As for the platform restriction, it has some convenient

constraints (for implementers), and my projects are often about shooting

multiple birds with one stone:

-

The longest path is MAX_PATH, a meager 260 pseudo-UTF-16 code points,

is nice and short. Technically users can now opt-in to a maximum path

length of 32,767, but so little software supports it, including

much of Windows itself, that it’s not worth considering. Even with the

upper limit, each path component is still restricted by MAX_PATH. I

can rely on this platform restriction in my design.

-

Symbolic links, an annoying edge case, are outside of consideration.

Technically Windows has them, but they’re sufficiently locked away that

they don’t come up in practice.

-

After years of deliberating, I was finally convinced to buy and

try RememdyBG, a super slick Windows debugger. I especially wanted

to try out its multi-threading support, and I knew I’d be using multiple

threads in this project. Since it’s incompatible with my development

kit, my program also supports the MSVC compiler.

-

The very same day I improved GDB support in my development kit,

and this was a great opportunity to dogfood the changes. I’ve used my

kit so much these past two years, especially since both it and I have

matured enough that I’m nearly as productive in it as I am on Linux.

-

It’s practice and experience with the wide API, and the tool

fully supports Unicode paths. Perhaps a bit unnecessary considering how

few source trees stray beyond ASCII, even just in source text — just too

many ways things go wrong otherwise.

Running my tool on nearly the same source tree as the original example

yields:

C:\openbsd>watc sys

. 6.89MLOC 364.58MiB

├─dev 5.69MLOC 332.75MiB

│ ├─pci 4.46MLOC 293.80MiB

│ │ ├─drm 3.99MLOC 280.25MiB

│ │ │ ├─amd 3.33MLOC 261.24MiB

│ │ │ │ ├─include 2.61MLOC 238.48MiB

│ │ │ │ │ ├─asic_reg 2.53MLOC 235.07MiB

│ │ │ │ │ │ ├─nbio 689.56kLOC 69.33MiB

│ │ │ │ │ │ ├─dcn 583.67kLOC 58.60MiB

│ │ │ │ │ │ ├─gc 290.26kLOC 28.90MiB

│ │ │ │ │ │ ├─dce 210.16kLOC 16.81MiB

│ │ │ │ │ │ ├─mmhub 155.60kLOC 16.03MiB

│ │ │ │ │ │ ├─dpcs 123.90kLOC 12.97MiB

│ │ │ │ │ │ ├─gca 105.91kLOC 5.87MiB

│ │ │ │ │ │ ├─bif 71.45kLOC 4.41MiB

│ │ │ │ │ │ ├─gmc 64.24kLOC 3.41MiB

│ │ │ │ │ │ └─(other) 230.99kLOC 18.73MiB

│ │ │ │ │ └─(other) 2.10kLOC 139.29kiB

│ │ │ │ └─(other) 718.93kLOC 22.76MiB

│ │ │ └─(other) 583.63kLOC 16.86MiB

│ │ └─(other) 8.53kLOC 259.07kiB

│ └─(other) 1.20MLOC 38.34MiB

└─(other) 1.20MLOC 31.83MiB

In place of interactivity it has -n (lines) and -d (depth) switches to

control tree pruning, where branches are summarized as (other) entries.

My idea is for users to run the tool repeatedly with different cutoffs and

filters to get a feel for where’s all the code. (It could really use

more such knobs.) Repeated counting makes performance all the more

important. On my machine, and a hot cache, the above takes ~180ms to count

those 6.89 million lines of code across 8,607 source files.

Each directory is treated like one big source file of its recursively

concatenated contents, so the tool only needs to track directories. Each

directory entry comprises a variable-length string name, line and byte

totals, and tree linkage such that it can be later navigated for sorting

and printing. That linkage has a clever solution, which I’ll get to later.

First, lets deal with strings.

String management

It’s important to get out of the null-terminated string business early,

only reverting to their use at system boundaries, such as constructing

paths for the operating system. Better to handle strings as offset/length

pairs into a buffer. Definitely avoid silly things like allocating many

individual strings, as encouraged by strdup — and most other

programming language idioms — and certainly avoid useless functions like

strcpy.

When the operating system provides a path component that I need to track

for later, I intern it into a single, large buffer. That buffer looks like

so:

#define BUF_MAX (1 << 22)

struct buf {

int32_t len;

wchar_t buf[BUF_MAX];

};

Empirically I determined that even large source trees cumulatively total

on the order of 10,000 characters of directory names. The OpenBSD kernel

source tree is only 2,992 characters of names.

$ find sys -type d -printf %f | wc -c

2992

The biggest I found was the LLVM source tree at 121,720 characters, not

only because of its sheer volume but also because it has generally has

relatively long names. So for my maximum buffer size I just maxed it out

(explained in a moment) and called it good. Even with UTF-16, that’s only

8MiB which is perfectly reasonable to allocate all at once up front. Since

my string handles don’t contain pointers, this buffer could be freely

relocated in the case of realloc.

The operating system provides a null-terminated string. The buffer makes a

copy and returns a handle. A handle is a 32-bit integer encoding offset

and length.

int32_t buf_push(struct buf *b, wchar_t *s)

{

int32_t off = b->len;

int32_t len = wcslen(s);

if (b->len+len > BUF_MAX) {

return -1; // out of memory

}

memcpy(b->buf+off, s, len*sizeof(*s));

b->len += len;

return len<<22 | off;

}

The negative range is reserved for errors, leaving 31 bits. I allocate 9

to the length — enough for MAX_PATH of 260 — and the remaining 22 bits

for the buffer offset, exactly matching the range of my BUF_MAX.

Splitting on a nibble boundary would have displayed more nicely in

hexadecimal during debugging, but oh well.

A couple of helper functions are in order:

int str_len(int32_t s) { return s >> 22; }

int32_t str_off(int32_t s) { return s & 0x3fffff; }

Rather than allocate the string buffer on the heap, it’s a static (read:

too big for the stack) scoped to main. I consistently call it b.

That’s string management solved efficiently in a dozen lines of code. I

briefly considered a hash table to de-duplicate strings in the buffer, but

real source trees aren’t redundant enough to make up for the hash table

itself, plus there’s no reason here to make that sort of time/memory

trade-off.

Directory entries

I settled on 24-byte directory entries:

struct dir {

uint64_t nbytes;

uint32_t nlines;

int32_t name;

int32_t link;

int32_t nsubdirs;

};

For nbytes I teetered between 32 bits and 64 bits for the byte count. No

source tree I found overflows an unsigned 32-bit integer, but LLVM comes

close, just barely overflowing a signed 31-bit integer as of this year.

Since I wanted 10x over the worst case I could find, that left me with a

64-bit integer for bytes.

For nlines, 32 bits has plenty of overhead. More importantly, this field

is updated concurrently and atomically by multiple threads — line counting

is parallelized — and I want this program to work on 32-bit hosts limited

to 32-bit atomics.

The name is the string handle for that directory’s name.

The link and nsubdirs is the tree linkage. The link field is an

index, and serves two different purposes at different times. Initially it

will identify the directory’s parent directory, and I had originally named

it parent. nsubdirs is the number of subdirectories, but there is

initially no link to a directory’s children.

Like with the buffer, I pre-allocate all the directory entries I’ll need:

#define DIRS_MAX (1 << 17)

int32_t ndirs = 0;

static struct dir dirs[DIRS_MAX];

A directory handle is just an index into dirs. The link field is one

such handle. Like string handles, directory entries contain no pointers,

and so this dirs buffer could be freely relocated, a la realloc, if

the context called for such flexibility. In my program, rather than

allocate this on the heap, it’s just a static (read: too big for the

stack) scoped to main.

For DIRS_MAX, I again looked at the worst case I could find, LLVM, which

requires 12,163 entries. I had hoped for 16-bit directory handles, but

that would limit source trees to 32,768 directories — not quite 10x over

the worst case. I settled on 131,072 entries: 3MiB. At only 11MiB total so

far, in the very worst case, it hardly matters that I couldn’t shave off

these extra few bytes.

$ find llvm-project -type d | wc -l

12163

Allocating a directory entry is just a matter of bumping the ndirs

counter. Reading a directory into dirs looks roughly like so:

int32_t glob = buf_push(&b, L"*");

static struct dir dirs[DIRS_MAX];

int32_t parent = ...; // an existing directory handle

wchar_t path[MAX_PATH];

buildpath(path, &b, dirs, parent, glob);

WIN32_FIND_DATAW fd;

HANDLE h = FindFirstFileW(path, &fd);

do {

if (FILE_ATTRIBUTE_DIRECTORY & fd.dwFileAttributes) {

int32_t name = buf_push(&b, fd.cFileName);

if (name < 0 || ndirs == DIRS_MAX) {

// out of memory

}

int32_t i = ndirs++;

dirs[i].name = name;

dirs[i].link = parent;

dirs[parent].nsubdirs++;

} else {

// ... process file ...

}

} while (FindNextFileW(h, &fd));

CloseHandle(h);

Mentally bookmark that “process file” part. It will be addressed later.

The buildpath function walks the link fields, copying (memcpy) path

components from the string buffer into the path, separated by

backslashes.

Breadth-first tree traversal

At the top-level the program must first traverse a tree. There are two

strategies for traversing a tree (or any graph):

- Depth-first: stack-oriented (lends to recursion)

- Breadth-first: queue-oriented

Recursion makes me nervous, but besides this, a queue is already a natural

fit for this problem. The tree I build in dirs is also the breadth-first

processing queue. (Note: This is entirely distinct from the message

queue that I’ll introduce later, and is not a concurrent queue.) Further,

building the tree in dirs via breadth-first traversal will have useful

properties later.

The queue is initialized with the root directory, then iterated over until

the iterator reaches the end. Additional directories may added during

iteration, per the last section.

int32_t root = ndirs++;

dirs[root].name = buf_push(&b, L".");

dirs[root].link = -1; // terminator

for (int32_t parent = 0; parent < ndirs; parent++) {

// ... FindFirstFileW / FindNextFileW ...

}

When the loop exits, the program has traversed the full tree. Counts are

now propagated up the tree using the link field, pointing from leaves to

root. In this direction it’s just a linked list. Propagation starts at the

root and works towards leaves to avoid multiple-counting, and the

breadth-first dirs is already ordered for this.

for (int32_t i = 1; i < ndirs; i++) {

for (int32_t j = dirs[i].link; j >= 0; j = dirs[j].link) {

dirs[j].nbytes += dirs[i].nbytes;

dirs[j].nlines += dirs[i].nlines;

}

}

Since this is really another traversal, this could be done during the

first traversal. However, line counting will be done concurrently, and

it’s easier, and probably more efficient, to propagate concurrent results

after the concurrent part of the code is complete.

Inverting the tree links

Printing the graph will require a depth-first traversal. Given an entry,

the program will iterate over its children. However, the tree links are

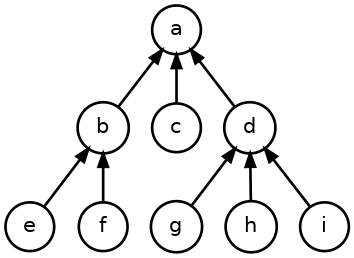

currently backwards, pointing from child to parent:

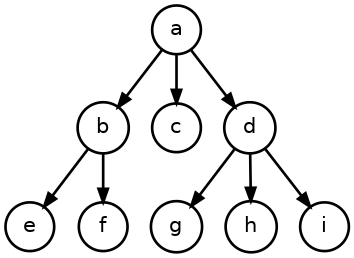

To traverse from root to leaves, those links will need to be inverted:

However, there’s only one link on each node, but potentially multiple

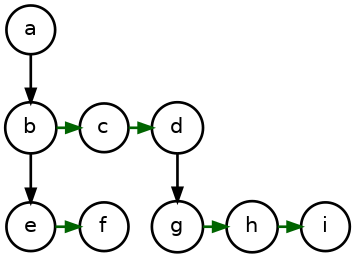

children. The breadth-first traversal comes to the rescue: All child nodes

for a given directory are adjacent in dirs. If link points to the

first child, finding the rest is trivial. There’s an implicit link between

siblings by virtue of position:

An entry’s first child immediately follows the previous entry’s last

child. So to flip the links around, manually establish the root’s link

field, then walk the tree breadth-first and hook link up to each entry’s

children based on the previous entry’s link and nsubdirs:

dirs[0].link = 1;

for (int32_t i = 1; i < ndirs; i++) {

dirs[i].link = dirs[i-1].link + dirs[i-1].nsubdirs;

}

The tree is now restructured for sorting and depth-first traversal.

Sort by line count

I won’t include it here, but I have a qsort-compatible comparison

function, dircmp that compares by line count descending, then by name

ascending. As a file system tree, siblings cannot have equal names.

int dircmp(const void *, const void *);

Since child entries are adjacent, it’s a trivial to qsort each entry’s

children. A loop sorts the whole tree:

for (int32_t i = 0; i < ndirs; i++) {

struct dir *beg = dirs + dirs[i].link;

qsort(beg, dirs[i].nsubdirs, sizeof(*dirs), dircmp);

}

We’re almost to the finish line.

Depth-first traversal

As I said, recursion makes me nervous, so I took the slightly more

complicated route of an explicit stack. Path components must be separated

by a backslash delimiter, so the deepest possible stack is MAX_PATH/2.

Each stack element tracks a directory handle (d) and a subdirectory

index (i).

I have a printstat to output an entry. It takes an entry, the string

buffer, and a depth for indentation level.

void printstat(struct dir *d, struct buf *b, int depth);

Here’s a simplified depth-first traversal calling printstat. (The real

one has to make decisions about when to stop and summarize, and it’s

dominated by edge cases.) I initialize the stack with the root directory,

then loop until it’s empty.

int n = 0; // top of stack

struct {

int32_t d;

int32_t i;

} stack[MAX_PATH/2];

stack[n].d = 0;

stack[n].i = 0;

printstat(dirs+0, &b, n);

while (n >= 0) {

int32_t d = stack[n].d;

int32_t i = stack[n].i++;

if (i >= dirs[d].nsubdirs) {

n--; // pop

} else {

int32_t cur = dirs[d].link + i;

printstat(dirs+cur, &b, n);

n++; // push

stack[n].d = cur;

stack[n].i = 0;

}

}

Concurrency

At this point the “process file” part of traversal was a straightforward

CreateFile, ReadFile loop, CloseHandle. I suspected it spent most of

its time in the loop counting newlines since I didn’t do anything special,

like SIMD, aside from not over-constraining code

generation.

However after taking some measurements, I found the program was spending

99.9% its time waiting on Win32 functions. CreateFile was the most

expensive at nearly 50% of the total run time, and even CloseHandle was

a substantial blocker. These two alone meant overlapped I/O wouldn’t help

much, and threads were necessary to run these Win32 blockers concurrently.

Counting newlines, even over gigabytes of data, was practically free, and

so required no further attention.

So I set up my lock-free work queue.

#define QUEUE_LEN (1<<15)

struct queue {

uint32_t q;

int32_t d[QUEUE_LEN];

int32_t f[QUEUE_LEN];

};

As before, q here is the atomic. A max-size queue for QUEUE_LEN worked

best in my tests. Larger queues were rarely full. Or empty, except at

startup and shutdown. Queue elements are a pair of directory handle (d)

and file string handle (f), stored in separate arrays.

I didn’t need to push the file name strings into the string buffer before,

but now it’s a great way to supply strings to other threads. I push the

string into the buffer, then send the handle through the queue. The

recipient re-constructs the path on its end using the directory tree and

this file name. Unfortunately this puts more stress on the string buffer,

which is why I had to max out the size, but it’s worth it.

The “process files” part now looks like this:

dirs[parent].nbytes += fd.nFileSizeLow;

dirs[parent].nbytes += (uint64_t)fd.nFileSizeHigh << 32;

int32_t name = buf_push(&b, fd.cFileName);

if (!queue_send(&queue, parent, name)) {

wchar_t path[MAX_PATH];

buildpath(path, buf.buf, dirs, parent, name);

processfile(path, dirs, parent);

}

If queue_send() returns false then the queue is full, so it processes

the job itself. There might be room later for the next file.

Worker threads look similar, spinning until an item arrives in the queue:

for (;;) {

int32_t d;

int32_t name;

while (!queue_recv(q, &d, &name));

if (d == -1) {

return 0;

}

wchar_t path[MAX_PATH];

buildpath(path, buf, dirs, d, name);

processfile(path, dirs, d);

}

A special directory entry handle of -1 tells the worker to exit. When

traversal completes, the main thread becomes a worker until the queue

empties, pushes one termination handle for each worker thread, then joins

the worker threads — a synchronization point that indicates all work is

complete, and the main thread can move on to propagation and sorting.

This was a substantial performance boost. At least on my system, running

just 4 threads total is enough to saturate the Win32 interface, and

additional threads do not make the program faster despite more available

cores.

Aside from overall portability, I’m quite happy with the results.