nullprogram.com/blog/2013/01/26/

Four years ago I investigated the idea of using

browsers as nodes for distributed computing. I concluded

that due to the platform’s constraints there were few problems that it

was suited to solve. However, the situation has since changed quite a

bit! In fact, this weekend I made practical use of web browsers across

a number of geographically separated computers to solve a

computational problem.

What changed?

Web workers came into existence, not just as a specification

but as an implementation across all the major browsers. It allows for

JavaScript to be run in an isolated, dedicated background thread. This

eliminates the setTimeout() requirement from before, which not only

caused a performance penalty but really hampered running any sort of

lively interface alongside the computation. The interface and

computation were competing for time on the same thread.

The worker isn’t entirely isolated; otherwise it would be useless

for anything but wasting resources. As pubsub events, it can pass

structured clones to and from the main thread running in the

page. Other than this, it has no access to the DOM or other data on

the page.

The interface is a bit unfriendly to live development, but

it’s manageable. It’s invoked by passing the URL of a script to the

constructor. This script is the code that runs in the dedicated thread.

var worker = new Worker('script/worker.js');

The sort of interface that would have been more convenient for live

interaction would be something like what is found on most

multi-threaded platforms: a thread constructor that accepts a function

as an argument.

/* This doesn't work! */

var worker = new Worker(function() {

// ...

});

I completely understand why this isn’t the case. The worker thread

needs to be totally isolated and the above example is insufficient.

I’m passing a closure to the constructor, which means I would be

sharing bindings, and therefore data, with the worker thread. This

interface could be faked using a data URI and taking

advantage of the fact that most browsers return function source code

from toString().

Another difficulty is libraries. Ignoring the stupid idea of

passing code through the event API and evaling it, that single URL

must contain *all* the source code the worker will use as one

script. This means if you want to use any libraries you'll need to

concatenate them with your script. That complicates things slightly,

but I imagine many people will be minifying their worker JavaScript

anyway.

Libraries can be loaded by the worker with the importScripts()

function, so not everything needs to be packed into one

script. Furthermore, workers can make HTTP requests with

XMLHttpRequest, so that data don’t need to be embedded either. Note

that it’s probably worth making these requests synchronously (third

argument false), because blocking isn’t an issue in workers.

The other big change was the effect Google Chrome, especially its V8

JavaScript engine, had on the browser market. Browser JavaScript is

probably about two orders of magnitude faster than it was when I wrote

my previous post. It’s

incredible what the V8 team has accomplished. If written

carefully, V8 JavaScript performance can beat out most other languages.

Finally, I also now have much, much better knowledge of JavaScript

than I did four years ago. I’m not fumbling around like I was before.

Applying these Changes

This weekend’s Daily Programmer challenge was to find a “key” —

a permutation of the alphabet — that when applied to a small

dictionary results in the maximum number of words with their letters

in alphabetical order. That’s a keyspace of 26!, or

403,291,461,126,605,635,584,000,000.

When I’m developing, I use both a laptop and a desktop simultaneously,

and I really wanted to put them both to work searching that huge space

for good solutions. Initially I was going to accomplish this by

writing my program in Clojure and running it on each machine. But what

about involving my wife’s computer, too? I wasn’t going to bother her

with setting up an environment to run my stuff. Writing it in

JavaScript as a web application would be the way to go. To coordinate

this work I’d use simple-httpd. And so it was born,

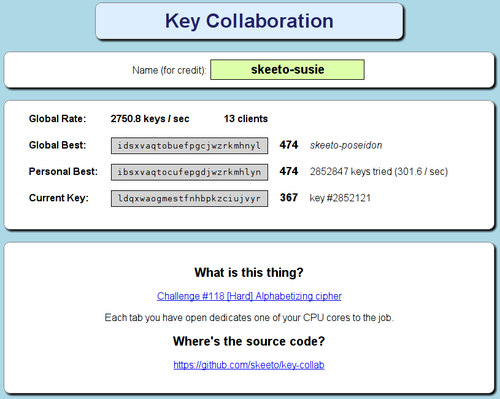

Here’s what it looks like in action. Each tab open consumes one CPU

core, allowing users to control their commitment by choosing how many

tabs to keep open. All of those numbers update about twice per second,

so users can get a concrete idea of what’s going on. I think it’s fun

to watch.

(I’m obviously a fan of blues and greens on my web pages. I don’t know why.)

I posted the server’s URL on reddit in the challenge thread, so

various reddit users from around the world joined in on the

computation.

Strict Mode

I had an accidental discovery with strict mode and

Chrome. I’ve always figured using strict mode had an effect on the

performance of code, but had no idea how much. From the beginning, I

had intended to use it in my worker script. Being isolated already,

there are absolutely no downsides.

However, while I was developing and experimenting I accidentally

turned it off and left it off. It was left turned off for a short time

in the version I distributed to the clients, so I got to see how

things were going without it. When I noticed the mistake and

uncommented the "use strict" line, I saw a 6-fold speed boost in

Chrome. Wow! Just making those few promises to Chrome allowed it to

make some massive performance optimizations.

With Chrome moving at full speed, it was able to inspect 560 keys per

second on Brian’s laptop. I was getting about 300 keys per

second on my own (less-capable) computers. I haven’t been able to get

anything close to these speeds in any other language/platform (but I

didn’t try in C yet).

Furthermore, I got a noticeable speed boost in Chrome by using proper

object oriented programming, versus a loose collection of functions

and ad-hoc structures. I think it’s because it made me construct my

data structures consistently, allowing V8’s hidden classes to work

their magic. It also probably helped the compiler predict type

information. I’ll need to investigate this further.

Use strict mode whenever possible, folks!

What made this problem work?

Having web workers available was a big help. However, this problem met

the original constraints fairly well.

-

It was low bandwidth. No special per-client instructions were

required. The client only needed to report back a 26-character

string.

-

There was no state to worry about. The original version of my

script tried keys at random. The later version used a hill-climbing

algorithm, so there was some state but it was only needed for a

few seconds at a time. It wasn’t worth holding onto.

This project was a lot of fun so I hope I get another opportunity to

do it again in the future, hopefully with a lot more nodes

participating.