nullprogram.com/blog/2013/06/10/

On several occasions over the last few years I’ve tried to get into

OpenGL programming. I’d sink an afternoon into attempting to learn it,

only to get frustrated and quit without learning much. There’s a lot

of outdated and downright poor information out there, and a beginner

can’t tell the good from the bad. I tried using OpenGL from C++, then

Java (lwjgl), then finally JavaScript (WebGL). This

last one is what finally stuck, unlocking a new world of projects for

me. It’s been very empowering!

I’ll explain why WebGL is what finally made OpenGL click for me.

Old vs. New

I may get a few details wrong, but here’s the gist of it.

Currently there are basically two ways to use OpenGL: the old way

(compatibility profile, fixed-function pipeline) and the new way

(core profile, programmable pipeline). The new API came about

because of a specific new capability that graphics cards gained years

after the original OpenGL specification was written. This is, modern

graphics cards are fully programmable. Programs can be compiled with

the GPU hardware as the target, allowing them to run directly on the

graphics card. The new API is oriented around running these programs

on the graphics card.

Before the programmable pipeline, graphics cards had a fixed set of

functionality for rendering 3D graphics. You tell it what

functionality you want to use, then hand it data little bits at a

time. Any functionality not provided by the GPU had to be done on the

CPU. The CPU ends of doing a lot of the work that would be better

suited for a GPU, in addition to spoon-feeding data to the GPU during

rendering.

With the programmable pipeline, you start by sending a program, called

a shader, to the GPU. At the application’s run-time, the graphics

driver takes care of compiling this shader, which is written in the

OpenGL Shading Language (GLSL). When it comes time to render a frame,

you prepare all the shader’s inputs in memory buffers on the GPU, then

issue a draw command to the GPU. The program output goes into

another buffer, probably to be treated as pixels for the screen. On

it’s own, the GPU processes the inputs in parallel much faster than a

CPU could ever do sequentially.

An very important detail to notice here is that, at a high level,

this process is almost orthogonal to the concept of rendering

graphics. The inputs to a shader are arbitrary data. The final

output is arbitrary data. The process is structured so that it’s

easily used to render graphics, but it’s not strictly required. It can

be used to perform arbitrary computations.

This paradigm shift in GPU architecture is the biggest barrier to

learning OpenGL. The apparent surface area of the API is doubled in

size because it includes the irrelevant, outdated parts. Sure, the

recent versions of OpenGL eschew the fixed-function API (3.1+), but

all of that mess still shows up when browsing and searching

documentation. Worse, there are still many tutorials that teach the

outdated API. In fact, as of this writing the first Google result

for “opengl tutorial” turns up one of these outdated tutorials.

OpenGL ES and WebGL

OpenGL for Embedded Systems (OpenGL ES) is a subset of OpenGL

specifically designed for devices like smartphones and tablet

computers. The OpenGL ES 2.0 specification removes the old

fixed-function APIs. What’s significant about this is that WebGL is

based on OpenGL ES 2.0. If the context a discussion is WebGL, you’re

guaranteed to not be talking about an outdated API. This indicator has

been a really handy way to filter out a lot of bad information.

In fact, I think the WebGL specification is probably the

best documentation root for exploring OpenGL. None of the outdated

functions are listed, most of the descriptions are written in plain

English, and they all link out to the official documentation if

clarification or elaboration is needed. As I was learning WebGL it was

easy to jump around this document to find what I needed.

This is also a reason to completely avoid spending time learning the

fixed-function pipeline. It’s incompatible with WebGL and many modern

platforms. Learning it would be about as useful as learning Latin when

your goal is to communicate with people from other parts of the world.

The Fundamentals

Now that WebGL allowed me to focus on the relevant parts of OpenGL, I

was able to spend effort into figuring out the important stuff that

the tutorials skip over. You see, even the tutorials that are using

the right pipeline still do a poor job. They skip over the

fundamentals and dive right into 3D graphics. This is a mistake.

I’m a firm believer that

mastery lies in having a solid grip on the fundamentals.

The programmable pipeline has little built-in support for 3D graphics.

This is because OpenGL is at its essence a 2D API. The

vertex shader accepts something as input and it produces 2D vertices

in device coordinates (-1 to 1) as output. Projecting this something

to 2D is functionality you have to do yourself, because OpenGL won’t

be doing it for you. Realizing this one fact was what really made

everything click for me.

Many of the tutorials try to handwave this part. “Just use this

library and this boilerplate so you can ignore this part,” they say,

quickly moving on to spinning a cube. This is sort of like using an

IDE for programming and having no idea how a build system works. This

works if you’re in a hurry to accomplish a specific task, but it’s no

way to achieve mastery.

More so, for me the step being skipped is perhaps the most

interesting part of it all! For example, after getting a handle on

how things worked — without copy-pasting any boilerplate around — I

ported my OpenCL 3D perlin noise generator to GLSL.

Instead of saving off each frame as an image, this just displays it in

real-time. The CPU’s only job is to ask the GPU to render a new

frame at a regular interval. Other than this, it’s entirely idle. All

the computation is being done by the GPU, and at speeds far greater

than a CPU could achieve.

Side note: you may notice some patterns in the noise. This is because,

as of this writing, I’m still working out decent a random number

generation in the fragment shader.

If your computer is struggling to display that page it’s because the

WebGL context is demanding more from your GPU than it can deliver. All

this GPU power is being put to use for something other than 3D

graphics! I think that’s far more interesting than a spinning 3D cube.

Spinning 3D Sphere

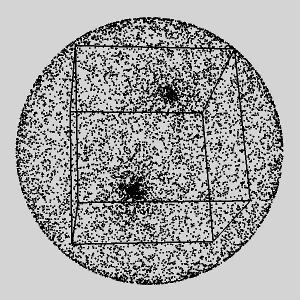

However, speaking of 3D cubes, this sort of thing was actually my very

first WebGL project. To demonstrate the

biased-random-point-on-a-sphere thing to a co-worker (outside

of work), I wrote a 3D HTML5 canvas plotter. I didn’t know WebGL yet.

On a typical computer this can only handle about 4,000 points before

the framerate drops. In my effort to finally learn WebGL, I ported the

display to WebGL and GLSL. Remember that you have to bring your own 3D

projection to OpenGL? Since I had already worked all of that out for

the 2D canvas, this was just a straightforward port to GLSL. Except

for the colored axes, this looks identical to the 2D canvas version.

This version can literally handle millions of points without

breaking a sweat. The difference is dramatic. Here’s 100,000 points in

each (any more points and it’s just a black sphere).

A Friendly API

WebGL still three major advantages over other OpenGL bindings, all of

which make it a real joy to use.

Length Parameters

In C/C++ world, where the OpenGL specification lies, any function that

accepts an arbitrary-length buffer must also have an parameter for the

buffer’s size. Due to this, these functions tend to have a lot of

parameters! So in addition to OpenGL’s existing clunkiness there are

these length arguments to worry about.

Not so in WebGL! Since JavaScript is a type-safe language, the buffer

lengths are stored with the buffers themselves, so this parameter

completely disappears. This is also an advantage of Java’s lwjgl.

Resource Management

Any time a shader, program, buffer, etc. is created, resources are

claimed on the GPU. Long running programs need to manage these

properly, destroying them before losing the handle on them. Otherwise

it’s a GPU leak.

WebGL ties GPU resource management to JavaScript’s garbage collector.

If a buffer is created and then let go, the GPU’s associated resources

will be freed at the same time as the wrapper object in JavaScript.

This can still be done explicitly if tight management is needed, but

the GC fallback is there if it’s not done.

Because this is untrusted code interacting with the GPU, this part is

essential for security reasons. JavaScript programs can’t leak GPU

resources, even intentionally.

Unlike the buffer length advantage, lwjgl does not do this. You still

need to manage GPU resources manually in Java, just as you would C.

Live Interaction

Perhaps most significantly of all, I can

drive WebGL interactively with Skewer. If I expose shader

initialization properly, I can even update the shaders while the

display running. Before WebGL, live OpenGL interaction is something

that could only be achieved with the Common Lisp OpenGL bindings (as

far as I know).

It’s really cool to be able to manipulate an OpenGL context from

Emacs.

The Future

I’m expecting to do a lot more with WebGL in the future. I’m really

keeping my eye out for an opportunity to combine it with

distributed web computing, but using the GPU instead of the

CPU. If I find a problem that fits this infrastructure well, this

system may be the first of its kind: visit a web page and let it use

your GPU to help solve some distributed computing problem!