nullprogram.com/blog/2014/01/26/

A couple of weeks ago I wrote a library to measure the retained memory

footprint of arbitrary Elisp objects for the purposes of optimization.

It’s called Caliper.

Note, Caliper requires predd, my predicate dispatch library.

Neither of these packages are on MELPA or Marmalade since they’re

mostly for fun.

The reason I wanted this was that I came across a post on reddit where

someone had scraped 217,000 Jeopardy! questions from

J! Archive and dumped them out into a single, large JSON

file. The significance of the effort is that it dealt with some of the

inconsistencies of J! Archive’s data presentation, normalizing them

for the JSON output.

When I want to examine a JSON dataset like this I have three preferred

options:

- Load it into a browser page and poke at it from JavaScript remotely

with Skewer. With the JSON text weighing in at 53MB and

with such a large object count, I decided this was too large for a

browser page. It definitely could be done, it’s just that the

browser is not the place to be working on large datasets.

- Load it into Clojure. I’m familiar with Clojure’s

data.json. This is not a bad choice, but there’s

something else I always reach for first if I can.

- Load it into Emacs using json.el (part of Emacs). This is what I

ended up doing.

(defvar jeopardy

(with-temp-buffer

(insert-file-contents "/tmp/JEOPARDY_QUESTIONS1.json")

(json-read)))

(length jeopardy)

;; => 216930

Here, jeopardy is bound to a vector of 216,930 association lists

(alists). I’m curious exactly how much heap memory this data structure

is using. To find out, we need to walk the data structure and sum the

sizes of everything we come across. However, care must be taken not to

count the identical objects twice, such as symbols, which, being

interned, appear many times in this data.

Measuring Object Sizes

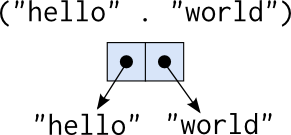

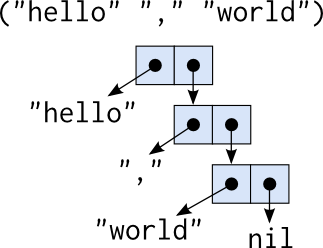

This is lisp so let’s start with the cons cell. A cons cell is just a

pair of pointers, called car and cdr.

These are used to assemble lists.

So a cons cell itself — the shallow size — is two words: 16 bytes

on a 64-bit operating system. To make sure Elisp doesn’t happen to

have any additional information attached to cons cells, let’s take a

look at the Emacs source code.

struct Lisp_Cons

{

/* Car of this cons cell. */

Lisp_Object car;

union

{

/* Cdr of this cons cell. */

Lisp_Object cdr;

/* Used to chain conses on a free list. */

struct Lisp_Cons *chain;

} u;

};

The return value from garbage-collect backs this up. The first value

after each type is the shallow size of that type. From here on, all

values have been computed for 64-bit Emacs running on x86-64

GNU/Linux.

(garbage-collect)

;; => ((conses 16 9923172 2036943)

;; (symbols 48 57017 54)

;; (miscs 40 10203 18892)

;; (strings 32 4810027 197961)

;; (string-bytes 1 104599635)

;; (vectors 16 103138)

;; (vector-slots 8 2921744 131076)

;; (floats 8 12494 5816)

;; (intervals 56 119911 69249)

;; (buffers 960 134)

;; (heap 1024 593412 133853))

A Lisp_Object is just a pointer to a lisp object. The retained

size of a cons cell is its shallow size plus, recursively, the

retained size of the objects in its car and cdr.

Integers and Floats

Integers are a special case. Elisp uses what is called tagged

integers. They’re not heap-allocated objects. Instead they’re

embedded inside the object pointers. That is, those Lisp_Object

pointers in Lisp_Cons will hold integers directly. This means to

Caliper integers have retained size of 0. We can use this to verify

Caliper’s return value for cons cells.

(caliper-object-size 100)

;; => 0

(caliper-object-size (cons 100 200))

;; => 16

Tagged integers are fast and save on memory. They also compare

properly with eq, which is just a pointer (identity) comparison.

However, because a few bits need to be reserved for differentiating

them from actual pointers these integers have a restricted dynamic

range.

Floats are not tagged and exist as immutable objects in the heap.

That’s why eql is still useful in Elisp — it’s like eq but will

handle numbers properly. (By convention you should use eql for

integers, too.)

Symbols and Strings

Not counting the string’s contents, a string’s base size is 32 bytes

according to garbage-collect. The length of the string can’t be

used here because that counts characters, which vary in size. There’s

a string-bytes function for this. A string’s size is 32 plus its

string-bytes value.

(string-bytes "naïveté")

;; => 9

(caliper-object-size "naïveté")

;; => 41 (i.e. 32 + 9)

As you can see from above, symbols are huge. Without even counting

either the string holding the name of the symbol or the symbol’s

plist, a symbol is 48 bytes.

(caliper-object-size 'hello)

;; => 1038

This 1,038 bytes is a little misleading. The symbol itself is 48

bytes, the string "hello" is 37 bytes, and the plist is nil. The

retained size of nil is significant. On my system, nil’s plist has 4

key-value pairs, which themselves have retained sizes. When examining

symbols, caliper doesn’t care if they’re interned or not, including

symbols like nil and t. However, nil is only counted once, so it

will have little impact on a large data structure.

Miscellaneous

Outside of vectors, measuring object sizes starts to get fuzzy. For

example, it’s not possible to examine the exact internals of a hash

table from Elisp. We can see its contents and the number of elements

it can hold without re-sizing, but there’s intermediate structure

that’s not visible. Caliper makes rough estimates for each of these

types.

Circularity and Double Counting

To avoid double counting objects, a hash table with a test of eq is

dynamically bound by the top level call. It’s used like a set. Before

an object is examined, the hash table is checked. If the object is

listed, the reported size is 0 (it consumes no additional space than

already accounted for).

This automatically solves the circularity problem. There’s no way we

can traverse into the same data structure a second time because we’ll

stop when we see it twice.

Using Caliper

So what’s the total retained size of the jeopardy structure? About

124MB.

(caliper-object-size jeopardy)

;; => 130430198

For fun, let’s see if how much we can improve on this.

json.el will return alists for objects by default, but this can be

changed by setting json-object-type to something else. Initially I

thought maybe using plists instead would save space, but I later

realized that plists use exactly the same number of cons cells as

alists. If this doesn’t sound right, try to picture the cons cells

in your head (an exercise for the reader).

(defvar jeopardy

(let ((json-object-type 'plist))

(with-temp-buffer

(insert-file-contents "~/JEOPARDY_QUESTIONS1.json")

(setf (point) (point-min))

(json-read))))

(caliper-object-size jeopardy)

;; => 130430077 (plist)

Strangely this is 121 bytes smaller. I don’t know why yet, but in the

scope of 124MB that’s nothing.

So what do these questions look like?

(elt jeopardy 0)

;; => (:show_number "4680"

;; :round "Jeopardy!"

;; :answer "Copernicus"

;; :value "$200"

;; :question "..." ;; omitted

;; :air_date "2004-12-31"

;; :category "HISTORY")

They’re (now) plists of 7 pairs. All of the keys are symbols, and, as

such, are interned and consuming very little memory. All of the values

are strings. Surely we can do better here. The strings can be interned

and the numbers can be turned into tagged integers. The :category

values would probably be good candidates for conversion into symbols.

Here’s an interesting fact about Jeopardy! that can be exploited for

our purposes. While Jeopardy! covers a broad range of trivia,

it does so very shallowly. The same answers appear many

times. For example, the very first answer from our dataset,

Copernicus, appears 14 times. That makes even the answers good

candidates for interning.

(cl-loop for question across jeopardy

for answer = (plist-get question :answer)

count (string= answer "Copernicus"))

;; => 14

A string pool is trivial to implement. Just use a weak, equal hash

table to track strings. Making it weak keeps it from leaking memory by

holding onto strings for longer than necessary.

(defvar string-pool

(make-hash-table :test 'equal :weakness t))

(defun intern-string (string)

(or (gethash string string-pool)

(setf (gethash string string-pool) string)))

(defun jeopardy-fix (question)

(cl-loop for (key value) on question by #'cddr

collect key

collect (cl-case key

(:show_number (read value))

(:value (if value (read (substring value 1))))

(:category (intern value))

(otherwise (intern-string value)))))

(defvar jeopardy-interned

(cl-map 'vector #'jeopardy-fix jeopardy))

So how are we looking now?

(caliper-object-size jeopardy-interned)

;; => 83254322

That’s down to 79MB of memory. Not bad! If we print-circle this,

taking advantage of string interning in the printed representation, I

wonder how it compares to the original JSON.

(with-temp-buffer

(let ((print-circle nil))

(prin1 jeopardy-interned (current-buffer))

(buffer-size)))

;; => 45554437

About 44MB, down from JSON’s 53MB. With print-circle set to nil it’s about

48MB.