nullprogram.com/blog/2014/06/06/

The April 5th, 2014 draft of the ECMA-262 6th Edition

specification — a.k.a the next major version of

JavaScript/ECMAScript — contained a subtle, though very significant,

change to the semantics of the for loop (13.6.3.3). Loop variables

are now fresh bindings for each iteration of the loop: a

per-iteration binding. Previously loop variables were established

once for the entire loop, a per-loop binding. The purpose is an

attempt to fix an old gotcha that effects many languages.

If you couldn’t already tell, this is going to be another language

lawyer post!

Backup to C

To try to explain what this all means this in plain English, let’s

step back a moment and discuss what a for loop really is. I can’t

find a source for this, but I’m pretty confident the three-part for

loop originated in K&R C.

for (INITIALIZATION; CONDITION; ITERATION) {

BODY;

}

- Evaluate INITIALIZATION.

- Evaluate CONDITION. If zero (false), exit the

for.

- Evaluate BODY.

- Evaluate ITERATION and go to 2.

In the original C, and all the way up to C89, no variable declarations

were allowed in the initialization expression. I can understand why:

there’s a subtle complication, though it’s harmless in C. We’ll get to

that soon. Here’s a typical C89 for loop.

int count = 10;

/* ... */

int i;

for (i = 0; i < count; i++) {

double foo;

/* ... */

}

The variable i is established independent of the loop, in the scope

outside the for loop, alongside count. This isn’t even a per-loop

binding. As far as the language is concerned, it’s just a variable

that the loop happens to access and mutate. It’s very

assembly-language-like. Because C has block scoping, the body of the

for loop is another nested scope. The variable foo is in this scope,

reestablished on each iteration of the loop (per-iteration).

As an implementation detail, foo will reside at the same location

on the stack each time around the loop. If it’s accessed

before being initialized, it will probably hold the value from the

previous iteration, but, as far as the language is concerned, this is

just a happy, though undefined, coincidence.

C99 Loops

Fast forward to the end of the 20th century. At this point, other

languages have allowed variable declarations in the initialization

part for years, so it’s time for C to catch up with C99.

int count = 10;

/* ... */

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

double foo;

/* ... */

}

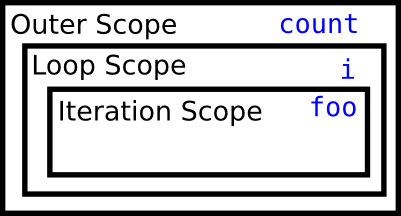

Now consider this: in what scope is the variable i? The outer

scope as before? The iteration scope with foo? The answer is

neither. In order to make this work, a whole new loop scope is

established in between: a per-loop binding. This scope holds for the

entire duration of the loop.

The variable i is constrained to the for loop without being

limited to the iteration scope. This is important because i is what

keeps track of the loop’s progress. The semantic equivalent in C89

makes the additional scope explicit with a block.

int count = 10;

/* ... */

{

int i;

for (i = 0; i < count; i++) {

double foo;

/* ... */

}

}

This, ladies and gentlemen, is the the C-style 3-part for loop.

Every language that has this statement, and has block scope, follows

these semantics. This included JavaScript up until two months ago,

where the draft now gives it its own unique behavior.

JavaScript’s Let

As it exists today in its practical form, little of the above is

relevant to JavaScript. JavaScript has no block scope, just function

scope. A three-part for-loop doesn’t establish all these scopes,

because scopes like these are absent from the language.

An important change coming with 6th edition is the introduction of

let declarations. Variables declared with let will have block

scope.

let count = 10;

// ...

for(let i = 0; i < count; i++) {

let foo;

// ...

}

console.log(foo); // error

console.log(i); // error

If these variables had been declared with var, the last two lines

wouldn’t be errors (or worse, global references). count, i, and

foo would all be in the same function-level scope. This is really

great! I look forward to using let exclusively someday.

The Closure Trap

I mentioned a subtle complication. Most of the time programmers don’t

need to consider or even be aware of this middle scope. However, when

combined with closures it suddenly becomes an issue. Here’s an example

with Perl,

my @closures;

for (my $i = 0; $i < 2; $i++) {

push(@closures, sub { return $i; });

}

$closures[0](); # => 2

$closures[1](); # => 2

Here’s one with Python. Python lacks a three-part for loop, but its

standard for loop has similar semantics.

closures = []

for i in xrange(2):

closures.append(lambda: i)

closures[0]() # => 1

closures[1]() # => 1

And now Ruby.

closures = []

for i in (0..1)

closures << lambda { i }

end

closures[0].call # => 1

closures[1].call # => 1

In all three cases, one closure is created per iteration. Each closure

captures the loop variable i. It’s easy to make the mistake of

thinking each closure will return a unique value. However, as pointed

out above, this is a per-loop variable, existing in a middle scope.

The closures all capture the same variable, merely bound to different

values at the time of capture. The solution is to establish a new

variable in the iteration scope and capture that instead. Below, I’ve

established a $value variable for this.

my @closures;

for (my $i = 0; $i < 2; $i++) {

my $value = $i;

push(@closures, sub { return $value; });

}

$closures[0](); # => 0

$closures[1](); # => 1

This is something that newbies easily get tripped up on. Because

they’re still trying to wrap their heads around the closure concept,

this looks like some crazy bug in the interpreter/compiler. I can

understand why the ECMA-262 draft was changed to accommodate this

situation.

The JavaScript Workaround

The language in the new draft has two items called

perIterationBindings and CreatePerIterationEnvironment (in case

you’re searching for the relevant part of the spec). Like the $value

example above, for loops in JavaScript with “lexical” (i.e. let)

loop bindings will implicitly mask the loop variable with a variable

of the same name in the iteration scope.

let closures = [];

for (let i = 0; i < 2; i++) {

closures.push(function() { return i; });

}

/* Before the change: */

closures[0](); // => 2

closures[1](); // => 2

/* After the change: */

closures[0](); // => 0

closures[1](); // => 1

Note: If you try to run this yourself, note that at the time of this

writing, the only JavaScript implementation I could find that updated

to the latest draft was Traceur. You’ll probably see the

“before” behavior for now.

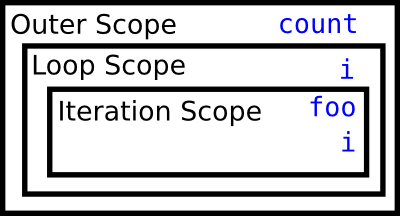

You can’t see it (I said it’s implicit!), but under an updated

JavaScript implementation there are actually two i variables here.

The closures capture the most inner i, the per-iteration version of

i. Let’s go back to the original example, JavaScript-style.

let count = 10;

// ...

for (let i = 0; i < count; i++) {

let foo;

// ...

}

Here’s what the scope looks like for the latest draft. Notice the

second i in the iteration scope. The inner i is initially assigned

to the value of the outer i.

We could emulate this in an older edition. Imagine writing a macro to

do this.

let count = 10;

// ...

for (let i = 0; i < count; i++) {

let __i = i; // (possible name collision)

{

let i = __i;

let foo;

// ...

}

}

I have to use __i to smuggle the value across scopes without having

i reference itself. Unlike Lisp’s let, the assignment value for

var and let is evaluated in the nested scope, not the outer scope.

Each iteration gets its own i. But what happens when the loop

modifies i? Simple, it’s copied back out at the end of the body.

let count = 10;

// ...

for (let i = 0; i < count; i++) {

let __i = i;

{

let i = __i;

let foo;

// ...

__i = i;

}

i = __i;

}

Now all the expected for semantics work — the body can also update

the loop variable — but we still get the closure-friendly

per-iteration variables.

Conclusion

I’m still not sure if I really like this change. It’s clean fix, but

the gotcha hasn’t been eliminated. Instead it’s been inverted.

Sometime someone will have the unusual circumstance of wanting to

capture the loop variable, and he will run into some surprising

behavior. Because the semantics are a lot more complicated, it’s hard

to reason about what’s not working unless you already know JavaScript

has magical for loops.

Perl and C# each also gained per-iteration bindings in their history,

but rather than complicate or change their standard for loops, they

instead introduced it as a new syntactic construction: foreach.

my @closures;

foreach my $i (0, 1) {

push(@closures, sub { return $i; });

}

$closures[0](); # => 0

$closures[1](); # => 1

In this case, per-iteration bindings definitely make sense. The

variable $i is established and bound to each value in turn. As far

as control flow goes, it’s very functional. The binding is never

actually mutated.

I think it could be argued that Python and Ruby’s for ... in forms

should behave like this foreach. These were probably misdesigned

early on, but it’s not possible to change their semantics at this

point. Because JavaScript’s var was improperly designed from the

beginning, let offers the opportunity to fix more than just var.

We’re seeing this right now with these new for semantics.