nullprogram.com/blog/2015/03/15/

Yesterday I completed my third entry to the annual Seven Day Roguelike

(7DRL) challenge (previously: 2013 and 2014). This

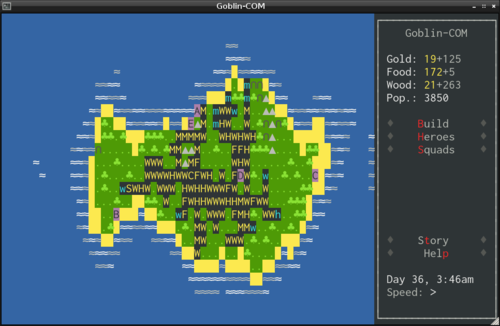

year’s entry is called Goblin-COM.

- Download/Source: Goblin-COM

- Telnet play (no saves):

telnet gcom.nullprogram.com

- Video review by Akhier Dragonheart

As with previous years, the ideas behind the game are not all that

original. The goal was to be a fantasy version of classic

X-COM with an ANSI terminal interface. You are the ruler of a

fledgling human nation that is under attack by invading goblins. You

hire heroes, operate squads, construct buildings, and manage resource

income.

The inspiration this year came from watching BattleBunny play

OpenXCOM, an open source clone of the original X-COM. It

had its major 1.0 release last year. Like the early days of

OpenTTD, it currently depends on the original game assets.

But also like OpenTTD, it surpasses the original game in every way, so

there’s no reason to bother running the original anymore. I’ve also

recently been watching One F Jef play Silent Storm, which is

another turn-based squad game with a similar combat simulation.

As in X-COM, the game is broken into two modes of play: the geoscape

(strategic) and the battlescape (tactical). Unfortunately I ran out of

time and didn’t get to the battlescape part, though I’d like to add it

in the future. What’s left is a sort-of city-builder with some squad

management. You can hire heroes and send them out in squads to

eliminate goblins, but rather than dropping to the battlescape,

battles always auto-resolve in your favor. Despite this, the game

still has a story, a win state, and a lose state. I won’t say what

they are, so you have to play it for yourself!

Terminal Emulator Layer

My previous entries were HTML5 games, but this entry is a plain old

standalone application. C has been my preferred language for the past

few months, so that’s what I used. Both UTF-8-capable ANSI terminals

and the Windows console are supported, so it should be perfectly

playable on any modern machine. Note, though, that some of the

poorer-quality terminal emulators that you’ll find in your Linux

distribution’s repositories (rxvt and its derivatives) are not

Unicode-capable, which means they won’t work with G-COM.

I didn’t make use of ncurses, instead opting to write my own

terminal graphics engine. That’s because I wanted a single, small

binary that was easy to build, and I didn’t want to mess around

with PDCurses. I’ve also been studying the Win32 API lately, so

writing my own terminal platform layer would rather easy to do anyway.

I experimented with a number of terminal emulators — LXTerminal,

Konsole, GNOME/MATE terminal, PuTTY, xterm, mintty, Terminator — but

the least capable “terminal” by far is the Windows console, so it

was the one to dictate the capabilities of the graphics engine. Some

ANSI terminals are capable of 256 colors, bold, underline, and

strikethrough fonts, but a highly portable API is basically limited

to 16 colors (RGBCMYKW with two levels of intensity) for each of the

foreground and background, and no other special text properties.

ANSI terminals also have a concept of a default foreground color and a

default background color. Most applications that output color (git,

grep, ls) leave the background color alone and are careful to choose

neutral foreground colors. G-COM always sets the background color, so

that the game looks the same no matter what the default colors are.

Also, the Windows console doesn’t really have default colors anyway,

even if I wanted to use them.

I put in partial support for Unicode because I wanted to use

interesting characters in the game (≈, ♣, ∩, ▲). Windows has supported

Unicode for a long time now, but since they added it too early,

they’re locked into the outdated UTF-16. For me this wasn’t

too bad, because few computers, Linux included, are equipped to render

characters outside of the Basic Multilingual Plane anyway, so

there’s no need to deal with surrogate pairs. This is especially true

for the Windows console, which can only render a very small set of

characters: another limit on my graphics engine. Internally individual

codepoints are handled as uint16_t and strings are handled as UTF-8.

I said partial support because, in addition to the above, it has no

support for combining characters, or any other situation where a

codepoint takes up something other than one space in the terminal.

This requires lookup tables and dealing with pitfalls, but

since I get to control exactly which characters were going to be used

I didn’t need any of that.

In spite of the limitations, I’m really happy with the graphical

results. The waves are animated continuously, even while the game is

paused, and it looks great. Here’s GNOME Terminal’s rendering, which I

think looked the best by default.

I’ll talk about how G-COM actually communicates with the terminal in

another article. The interface between the game and the graphics

engine is really clean (device.h), so it would be an interesting

project to write a back end that renders the game to a regular window,

no terminal needed.

Color Directive

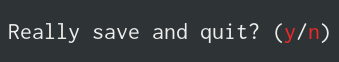

I came up with a format directive to help me colorize everything. It

runs in addition to the standard printf directives. Here’s an example,

panel_printf(&panel, 1, 1, "Really save and quit? (Rk{y}/Rk{n})");

The color is specified by two characters, and the text it applies to

is wrapped in curly brackets. There are eight colors to pick from:

RGBCMYKW. That covers all the binary values for red, green, and blue.

To specify an “intense” (bright) color, capitalize it. That means the

Rk{...} above makes the wrapped text bright red.

Nested directives are also supported. (And, yes, that K means “high

intense black,” a.k.a. dark gray. A w means “low intensity white,”

a.k.a. light gray.)

panel_printf(p, x, y++, "Kk{♦} wk{Rk{B}uild} Kk{♦}");

And it mixes with the normal printf directives:

panel_printf(p, 1, y++, "(Rk{m}) Yk{Mine} [%s]", cost);

Single Binary

The GNU linker has a really nice feature for linking arbitrary binary

data into your application. I used this to embed my assets into a

single binary so that the user doesn’t need to worry about any sort of

data directory or anything like that. Here’s what the make rule

would look like:

$(LD) -r -b binary -o $@ $^

The -r specifies that output should be relocatable — i.e. it can be

fed back into the linker later when linking the final binary. The -b

binary says that the input is just an opaque binary file (“plain”

text included). The linker will create three symbols for each input

file:

_binary_filename_start_binary_filename_end_binary_filename_size

When then you can access from your C program like so:

extern const char _binary_filename_txt_start[];

I used this to embed the story texts, and I’ve used it in the past to

embed images and textures. If you were to link zlib, you could easily

compress these assets, too. I’m surprised this sort of thing isn’t

done more often!

Dumb Game Saves

To save time, and because it doesn’t really matter, saves are just

memory dumps. I took another page from Handmade Hero and

allocate everything in a single, contiguous block of memory. With one

exception, there are no pointers, so the entire block is relocatable.

When references are needed, it’s done via integers into the embedded

arrays. This allows it to be cleanly reloaded in another process

later. As a side effect, it also means there are no dynamic

allocations (malloc()) while the game is running. Here’s roughly

what it looks like.

typedef struct game {

uint64_t map_seed;

map_t *map;

long time;

float wood, gold, food;

long population;

float goblin_spawn_rate;

invader_t invaders[16];

squad_t squads[16];

hero_t heroes[128];

game_event_t events[16];

} game_t;

The map pointer is that one exception, but that’s because it’s

generated fresh after loading from the map_seed. Saving and loading

is trivial (error checking omitted) and very fast.

void

game_save(game_t *game, FILE *out)

{

fwrite(game, sizeof(*game), 1, out);

}

game_t *

game_load(FILE *in)

{

game_t *game = malloc(sizeof(*game));

fread(game, sizeof(*game), 1, in);

game->map = map_generate(game->map_seed);

return game;

}

The data isn’t important enough to bother with rename+fsync

durability. I’ll risk the data if it makes savescumming that much

harder!

The downside to this technique is that saves are generally not

portable across architectures (particularly where endianness differs),

and may not even portable between different platforms on the same

architecture. I only needed to persist a single game state on the same

machine, so this wouldn’t be a problem.

Final Results

I’m definitely going to be reusing some of this code in future

projects. The G-COM terminal graphics layer is nifty, and I already

like it better than ncurses, whose API I’ve always thought was kind of

ugly and old-fashioned. I like writing terminal applications.

Just like the last couple of years, the final game is a lot simpler

than I had planned at the beginning of the week. Most things take

longer to code than I initially expect. I’m still enjoying playing it,

which is a really good sign. When I play, I’m having enough fun to

deliberately delay the end of the game so that I can sprawl my nation

out over the island and generate crazy income.